Grunge and Grind

A backward glance at College Hill’s Crunchy Music Stuff

By Billy Eye

“There’s a stigma to skating. People think of it as a kid’s sport. People kept telling me I couldn’t possibly make a living out of it. Then they said I couldn’t keep it up in my 30s. And here I am in my 40s, and I’m still improving my skills.” — Tony Hawk

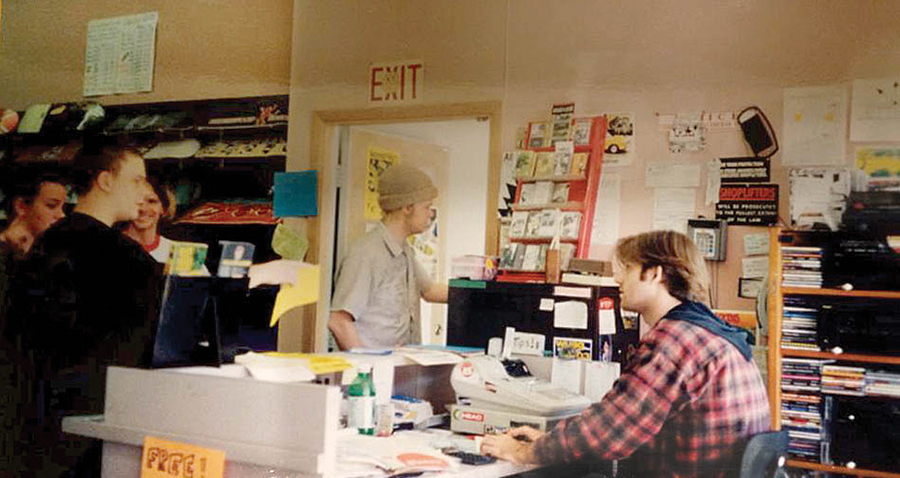

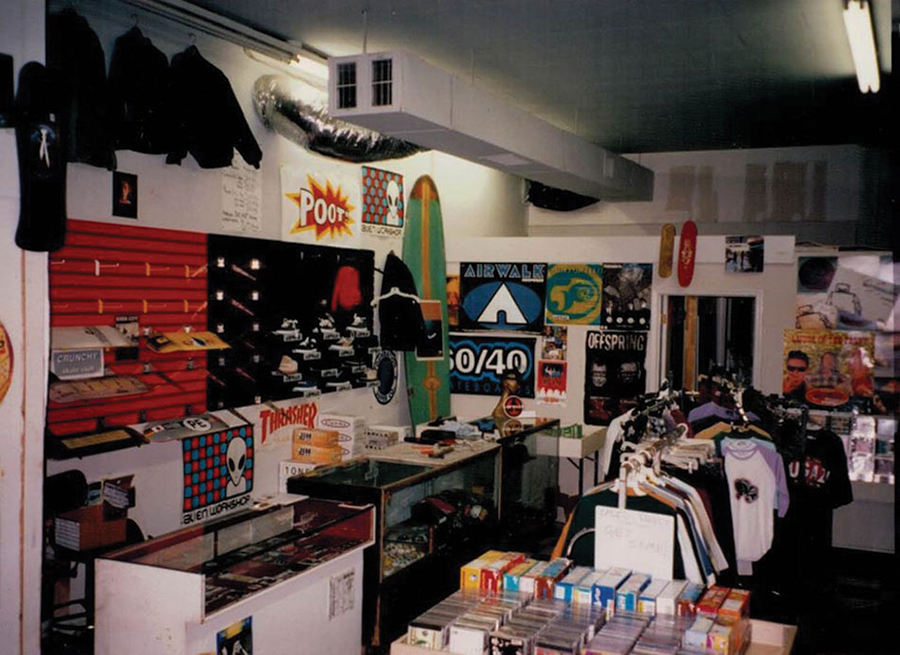

Just days ago, I commandeered a corner table at the Lindley Park Filling Station to reminisce with Michael Driver and Jae Skaggs, proprietors of one of our city’s most fondly remembered record retailers, Crunchy Music Stuff. Established in 1993, first at Spring Garden and Mendenhall then on the corner of Tate and Walker, for seven years Crunchy was the epicenter of Greensboro’s underground music and skateboard scene. Crunchy closed 20 years ago this year. As for how it started . . .

Michael: I blame Jae. The whole thing was your idea.

Jae: Was it? No, no, I think halfsies.

Michael: We were just nerds who didn’t want a job.

Jae: Right. We just sat around and talked about music anyway.

Michael: Somebody in Creamy Velour was playing at Infiniti. He worked at that record store out by the waterpark. He came up to me and said, “You know, they’re selling the store.” “Man that would be awesome to have a record store. How much?” It was like $250,000. I didn’t have any money. I was bitching about it that night and Jae said, “Why don’t you open your own record store?” Genius! We opened that store with a hundred CDs.

Jae: [The time period] was phase two of Grunge. Pavement broke out, Weezer broke while we were there.

Michael: You know who we sold a lot of? NOFX. And Green Day, we sold the hell out of that thing! They put out the first Beck record on an independent label, that “Loser” single was on a 12” EP. That we sold the hell out of. We were the only one in town that had that single.

Jae: Even before Napster, we started suffering when Best Buy opened. They bought every CD and sold everything for like nine bucks.

Michael: People would come in and say, “I just got this at Best Buy for $9.99,” and I’m like, “They’re losing money!” Nothing we could do but stock the stuff they didn’t have. So we mined our niche. That’s all any indie business can do. We had vinyl and nobody else did except for Record Exchange on Battleground; Ed LeBrun’s Spins had the electronic market locked up there. The punk rock stuff, that’s what we listened to and that made us money.

Jae: The flip side of that, the kick flip was, once people started coming in, we would get their used records. We paid as well as anybody else did, but in used records we had all of that indie punk catalog which other stores didn’t have.

Michael: We made money on Green Day because we sold thousands of them. We did well with Ill Communication [by The Beastie Boys]. It was a midnight release. We had like a hundred people there. Jae’s band Rebar was playing. There were so many people in the store it was like a sweaty New York nightclub. We sold every single copy we had, we went all in on that. It was one of the best nights we had, there were people lined up outside because they couldn’t get in, jumping up and down on the street.

Jae: Before the Internet you could do things like that. [Laughing] We were a legitimate business, generating revenue for the city.

Michael: Within the first week we had our first batch of skateboard items. That was Jae’s idea. I thought that was a great idea because nobody else was covering that market.

Jae: At the time there was no skate shop in town, I think the closest place was Winston, at EV, and they might have been gone by then. To keep both halves of the store alive it really worked out. Just barely, because there’s more overhead on skate stuff and it’s also seasonal. It’s also more of a gamble; you could really hit some duds and you will never sell them. Instead of, “oops, I bought too many $8 things,”[it was] “oops, I just bought too many $50 things.”

Michael: Every major skateboarder had their own shoe. We stocked Tony Hawks from Airwalk and we were the only ones that had them. We had The Beastie Boys’ weird, expandable clothing line, X-girl and XLARGE, those really big pants, even though I thought they were stupid but that’s what the skaters were wearing in the mid-1990s. Hook ups, Birdhouse, Girl, Stereo . . . we could buy clothes directly from the record labels.

Jae: We had Tony Hawk in the store, Shawn Briley, we had all these skateboarders appear. We also had vintage arcade games, which weren’t too vintage at the time, like the 720° skateboard game from the ’80s. I was very excited to see Tony Hawk playing that one in the store.

Michael: We got Tony Hawk for $500. It was a bargain at four times the price. For the record, I met Tony Hawk and I couldn’t speak. You meet your hero and it’s like, “Holy crap! It’s Tony Hawk!” So literally, that’s what I said, “Holy crap! It’s Tony Hawk!” I couldn’t think of anything else to say. The night before I stayed up all night to set up a half piperamp in the parking lot at Sam’s Club. The guys from Birdhouse Skateboards, Tony Hawk, Geoff Rowley, were there for a demo. We had like 200 people there, it was crazy.

Jae: Tony was recovering from a broken foot so he wasn’t fully skating. He rode just enough for the kids to love it. He wasn’t doing any 900s or anything like that. When you run a skateboard shop, to this day, you have to do that kind of thing.

Michael: We released four records on our own label, Crunchy Record Stuff. Two by Rebar, a 7-inch by Rights Reserved, “The Kids Are Not Alright,” and the fourth by The Get Gos. We recorded the Rebar album at the record store because it had that high ceiling, great acoustics.

Jae: We booked showcases at Somewhere Else Tavern and at Zoo Bar or Kilroy’s or Fuzzy Duck’s, I don’t remember because they would change the name every two or three years. And The Turtle Club at Lee and Aycock. They changed the name of both of those streets, that’s how notorious The Turtle Club was.

Michael: As far as how it ended, first I ran [employee] Scott Hicks off, then I ran Jae off.

Jae: I was kind of like eased out of [Crunchy], suddenly eased out of it, and then it kept on going. Michael kept it going so I didn’t take anything out of it. I didn’t take anything to remember it by, because I thought, “Well, It’s all going to be with Michael.” But I wonder why now, it was a big part of my life. Probably everything that has happened to me since then was because of that place. Both positive and negative.

Michael: I still have all that junk! I’ve got a bunch of posters, memorabilia from the record labels, all in two or three boxes in my attic.

The biggest year we had was ’96. By 1999, the skate shop started to decline and the record sales decliiiiiiined. Thank you Napster. By then Jae was gone, it was just me and an employee. In the mornings I would vomit. Then I would open the store. That’s what retail does to people, it makes you physically sick. After a few months of that I was like, “I don’t want to do this anymore.” About that time Andrew Dudek approached me about selling it all out to him and he basically bought the inventory and turned it into Gate City Noise, which was a much better concept because Andrew had all the connections with touring bands and it became an even bigger center of the music scene with the independent bands playing there.

You know, they have Record Store Day every year now, “Appreciate your local record store,” like Free Comic Book Day. About 20 years too late. . . I have yet to go to a Record Store Day event. I’m old and bitter! But I’m going to see Patrick at Hippo Records every week. Hippo carries the new stuff on vinyl. I’ve still got a thing for the vinyl. It’s an addiction. OH

Today Michael Driver is a successful realtor with RE/MAX of Greensboro while Jae Skaggs is an IT / System Administrator consultant. Both reside not too far from each other in Lindley Park. Next month, Billy Eye will tell you about Judy Garland’s life-changing Greensboro appearance.