Rasslin’ Hitchcock

Confessions of the ultimate fan

By Grant Britt

What a cool thing to get paid for: throwing people around, talking trash about them and achieving fame for basically being a bully. For a 12-year-old, it was a great exposure to the job market. We’re talking wrestling — or in these parts, rasslin’— toiling in the squared circle, an arena for modern-day gladiators to strut their stuff, sharing blood, sweat and tears with an audience of starstruck kids and rowdy adults. Interactive before that term came into being, rasslin’ let you get to get your ya-yas out up close and in person, shouting at the bad guys and rooting for the good ’uns from a ringside seat.

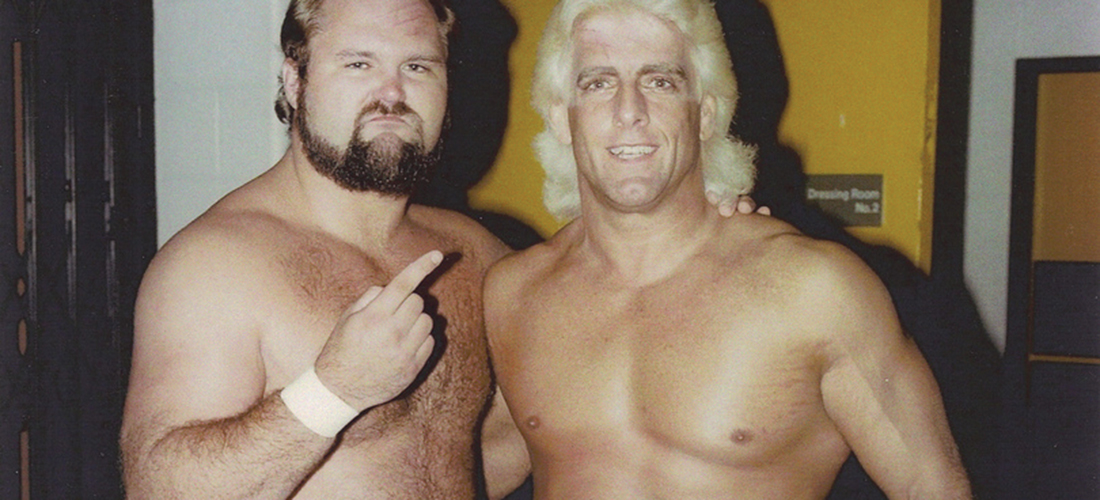

John Hitchcock couldn’t figure out a way to make a living at this ancient-sport-turned-raucous-theater, but he did manage to get involved — to a degree that most fans only dream about. He got to know some of the big stars, including Ric Flair and Arn Anderson, and even got some ring time as a bodyguard, actually taking hits from some of the renowned grapplers of the day.

He didn’t get any formal training in the sport, getting a Bachelor of Fine Arts degree in painting from Greensboro College instead. Then, he went back and got a teaching degree, but he found that things were rougher in the classroom than in the ring. “I’d love to be a teacher,” Hitchcock says. “But there’s no such thing as discipline.” So he went to work for a comic book store, putting in five and a half years at ACME comics before opening his own store, Parts Unknown, in 1989. But rasslin’ was still his first love, as the title of his store reflects: “That’s the way they always used to announce the masked rasslers,” Hitchcock says. “‘Ladies and gents, weight unknown, from parts unknown’ . . . and that’s where I got it from.”

Pro wrestling came to North Carolina in 1959 via WRAL-TV in Raleigh. It looked and sounded dangerous. Hosted in its infancy by local sports announcer and voice of the Wolfpack Ray Reeve, who always sounded as if he had just been resurrected and still had a throat full of graveyard dirt, the show was a brawling slugfest staffed with hulking bruisers who could talk smack as effortlessly as they could toss like-minded behemoths around. In ’64, promoter Jim Crockett brought the sport to Greensboro, with WGHP’s Charlie Harville as announcer. Championship Wrestling had a ten-year run here and changed John Hitchcock’s life.

“There were a lot of guys,” Hitchcock says, then goes on to name a who’s who list of rasslin’s golden age heroes and villains: Rip Hawk/Swede Hanson, Weaver/Becker, the Bolos, the Infernos, Aldo Bogni, Bronko Lubich. Haystacks Calhoun, Nelson Royal, Tex McKenzie, Brute Bernard and Skull Murphy, Wahoo McDaniel. “All that stuff is not a blur, it’s just there was such an amazing cast of characters — and characters is the key word. Every one of them was very different, and very odd,” Hitchcock remembers. “I was attracted to the oddity of it and the humor of it. It made me just fall in love with it. The first time I saw it, I was like, ‘This is the coolest thing.’”

So cool that many of us desperately wanted to be our newfound heroes and set about taunting our peers, trying out holds on siblings, schoolmates, casual acquaintances, or anybody small or young enough to have the misfortune of crossing our paths. And every week we were glued to the TV, soaking up more potentially deadly embraces and insults to share with unsuspecting opponents.

The show, broadcast when Harville worked for WGHP, became a weekly ritual for Hitchcock. “I was addicted to it. Even when I was working as a bag boy, I would get off at 11 on Saturday, get home as soon as I could so I could watch the 11:30 thing after the news. I always kept up with it and if I had an extra buck, I’d go to the show. [It] became part of my heritage, in a way — everybody went, everybody knew about it.”

But Hitchcock wanted more and worked himself up into a religious fervor to fulfill his ambition. “I sent a letter to [promoter Jim] Crockett, saying that I was a reverend in a small church and had a group of us [who] wanted to go to the show; could they please make sure we got in? They wrote me back a nice letter, said ‘Dear Rev. Hitchcock, we’d love to have your congregation.’ But I could only get three guys to go. My ‘church’ didn’t have a lot of followers.” The ruse, however, was successful, as Hitchcock recounts: “Crockett walked out and said, ‘We’re looking for Reverend Hitchcock and his followers,’ and I went, ‘We had a problem with the bus.’ We got to go in first, and they put us in the top of the bleachers in Raleigh and put us in like sardines, but we got in.”

From the get-go, Hitchcock had a little inside help getting to know the rasslers he so idolized. His older brother Sparky was an usher at the Greensboro Coliseum, and one of his duties was bringing refreshments to the athletes — “drinks and oranges” as Hitchcock notes in his rasslin’ tribute book, Front Row Section D. Sparky also provided John with backstage glimpses of the participants and hipped him to some of the sport’s jargon.

One of the first things he learned was how to identify the losers from their introductions. “Whenever they said ‘a wily veteran,’ he was gonna lose. And if it was a young guy, and if they said, ‘a young lion,’ he was gonna lose. Like a code. One guy’s up and coming, one guy’s fading out. They’re not gonna be players but they’re important to what’s going on.”

In rasslin’ lingo, the opposing groups were the heels, who were the bad guys, and the baby faces, the good guys.

“I used to cheer for the bad guys. There was just something about them. I always felt the bad guys were the guys that did all the work and all they got were boos and had drinks thrown on them, but without the bad guys there couldn’t be good guys.” Realizng early on the bad guys were much more entertaining, more humorous than the good guys, Hitchcock explains, “In the world of booking, the easiest way to make a baby-face guy is to create a heel that everybody hates. Then no matter who you put him against, they’re gonna cheer him to beat that guy up.”

But Hitchcock didn’t just cheer for his favorites. He and some buddies started getting front row seats to the matches here and making signs to carry in and hold up during the contests. The signs reflected Hitchcock’s acerbic sense of humor and quickly got noticed by fans and rasslers alike.

If you were ringside between 1984 and 1991, you saw Hitch: “I only missed two shows, and that was because of kidney failure,” Hitchcock says. “We were there on the front row, with our coats and ties and hats and sunglasses, stylin’ and profilin,’ cheering for the bad guys. And those guys would look forward to us; they were into it.”

Arn Anderson was one of the bad guys Hitchcock admired, and he returned the favor. “I got lucky, got to meet Arn on a couple of occasions. He always remembered me because I was the guy with the hat in Greensboro holding up the signs and cheering for him.” He first met Anderson when a buddy called Hitchcock on a pay phone from the Chicago airport and told him “You won’t believe this, but right beside me is Arn Anderson talking on the phone.” “‘Well, hell, man — put him on!’” Hitchcock told his friend, recalling the excitement of that first conversation with his idol. “And he tapped him on the shoulder and said ‘Your biggest fan wants to talk to you.’ And he handed [the receiver] to him, and he said ‘Hello,’ and I said, ‘Double A! You’re my hero!’ and he said, ‘Thanks, man,’ and I said, ‘This is John, the guy from Greensboro with the signs.’ And there was a pause and he said, ‘Greensboro. How’re you doing?’ and he started talking.”

Hitchcock says he doesn’t claim to be tight with Anderson, but the rasslin’ superstar always had time to visit when their paths crossed. “One of the times I went up to him and said, ‘We still love you in Greensboro,’ and he looked at me and went, ‘I know that voice, I know that face — Greensboro.’ And he said ‘Come on over here,’ and we sat down and talked for about forty-five minutes. Gave me that time; he was great.”

Some believed the access that Hitchcock had to the rasslers was from schmoozing with them in dens of iniquity after the shows, but Hitch says that was the furthest thing from the truth. “It’s funny, everybody thought we were going to bars and hanging out. Guess what? I don’t drink. I don’t smoke. I don’t do illegal drugs. I’m the straightest guy that ever walked the planet. What those guys would do is get in their cars and go to the next hotel or go to next show.” Hitchcock just had the nerve to walk right up and introduce himself, relying on his ringside persona to get close.

But others weren’t as gracious as Anderson. Hitchcock had it in for Dusty Rhodes and Rhodes actively hated him for it. Hitch got on Rhodes’ hit list with a sign that read “You Can Tell the Wrestler By Looking At His Blubber” (a riff on Rhodes’ theme song that played whenever he entered the ring, “You Can’t Tell a Book By Looking at the Cover”). Hitchcock later sharpened the barb with a caricature of Rhodes as the Michelin Man. Rhodes, who apparently was sensitive about his chubby physique, tried to spit on the Michelin sign but missed, marring the blouse of an older lady at ringside. Rhodes never actively came after Hitchcock, but there was an encounter in Florida during one of the rare times Hitchcock ventured into a bar. It was almost his last.

He was talking to WCW announcer Tony Schiavone when Rhodes’ son Dustin walked in, followed a minute later by “Michelin Man” himself. Hitchcock had greeted Dustin by razzing him about being rassler Dick Murdoch’s son, because he didn’t look anything like his daddy. But when Rhodes Senior came and sat down across the bar he looked over at Hitchcock and realized who he was. “I’m Greensboro,’” Hitchcock says. “And he smiles and he drinks his beer, gets up and walks over to Dustin and says, ‘You realize who you’re talkin’ to? Don’t talk to him anymore.’ The pudgy rassler took a more proactive approach with Schiavone, grabbing him by his coat lapels, pulling him face-to-face, “You’re talking to that asshole from Greensboro. Don’t talk to him.” Hitchcock was plenty uneasy at that point: “I was worried he might swing on me cause I’d heard he was pissed. And he didn’t — he just looked at me and smiled, finished his beer, grabbed Dustin, walked out of the bar. And I went to Schiavone and said, ‘He told you not to talk to me.’ And he said, ‘Yeah, that’s the weirdest thing. He’s never done that before. But man, he really does hold a grudge. He really hates your guts.’ And I went, ‘Well I hate his guts too.’”

Rhodes passed away in 2015, and Hitchcock has mellowed a bit on his Rhodes hate-fest. “He was one of the most charismatic guys in history of the business, one of the best talkers, one of the biggest stars in the world from’74–’86,” Hitchcock says before adding a caveat. “Had one of the biggest egos in the history of the business. And when I found out he was the booker, telling everybody who’s gonna win and who’s gonna lose, and then he won all he time, he put a target on himself as far as I was concerned, to make fun of him.” Hitchcock could get away with what the guys in the ring couldn’t and they encouraged him to keep it up.

Hitchcock acknowledges that when somebody of that stature passes away, you should point out the good as well as the bad. “I give credit where credit is due, but it’s hard to cheer for somebody when every time they’d come out they’d either grab their crotch or try to spit on you. So it was serious — it was a lot of heat.”

Hitchcock doesn’t bring much heat anymore. He’s as banged up as some of the famous rasslers he idolized. From a kidney transplant in ’88 and from a brief stint as a bodyguard in New Dimension Wrestling. “I would take one punch, fall down, act like I was knocked out, and that was it,” he says of his days in the ring.

These days, most of the superheroes he sees are on the walls and in the bins at his comic book store. He still watches rasslin’) on TV on Monday nights, and will go to one of the Indy shows if the accommodations are right. “If I sit on bleachers, it kills me,” he says. “I just turned 60, I know I’m no spring chicken anymore. I gotta have something with a little back support. If I have to sit on bleachers, screw it. But if they’ve got a metal chair, oh yeah, I’ll go.” At this point in his career, Hitch is at last content to leave the rasslin’ to the pros, and be just a spectator, in his corner, from parts unknown. OH

Fired up by the images of Rip Hawk and Swede Hanson on his hometown station, WRAL-TV, Grant Britt grew up rasslin’ everything ever suggested to him and has never stopped.

Photograph credit: Edward Cheslock