A scruffy old guitar finds its voice again

By Stephen E. Smith

Photographs by John Koob Gessner

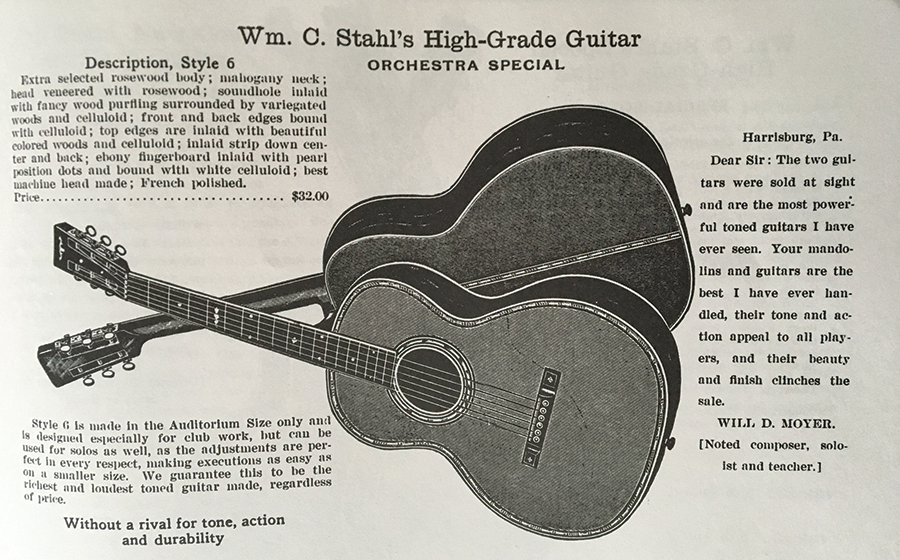

I’ll bet you’re nagged by a furtive longing to possess something that’s impractical. Maybe it’s Aunt Amelia’s Tiffany brooch or Granddad Ralph’s ’49 Mercury sedan. In my case, it’s always been a Stahl Style 6 guitar made by the Larson brothers of Chicago. Whatever the object, we know this: If we search long enough and can shell out the cash, we’re likely to get what we want. This is America; we invented conspicuous consumption.

Inspired by what comedian Martin Mull dubbed “The Great Folk Music Scare,” I bought my first guitar, a digit-mangling Kay archtop, in August 1961, from a pawn shop on West Street in Annapolis, Maryland. I was a rising eighth-grader and paid $15 I’d received for my birthday. Every Saturday that fall, I toted my caseless Kay to St. John’s College campus, where I sat under the last surviving Liberty Tree (on the very spot where patriots plotted the Revolution) and strummed “Goodnight, Irene” ad nauseam with five or six honest-to-God beatniks. On one of those cool autumn afternoons, a Maynard G. Krebs character handed me his guitar and said, “Here, give this a try.”

I strummed a G chord, one of the three I’d mastered. “Wow!” I said.

The proud owner beamed. “Plays like silk and chimes, like a chorus of seraphim,” he said.

“What kind of guitar is this?” I asked.

“It’s a Stahl 6,” he replied.

When I got home, I had to look up “seraphim” in the dictionary, but I knew in my bones what a Stahl guitar was.

For most of the 60-plus years that have slipped by since that autumn afternoon, I never happened upon a Stahl Style 6 I could afford. If I were a more accomplished player, I might have been willing to shell out $7,000 to $14,000 for a pristine original-condition Stahl, but alas . . .

And then, eight months ago, a Stahl Style 6 materialized on my computer screen — and it was for sale at a reasonable price! The rub: It was in sad — very sad — condition. The seller listed it as “Non Functioning,” noting that the Stahl was a “Luthier Project” afflicted with a “Non Original Bridge, Non Original Tuners, No Pins, Back Cracks with washboarding” — and an all-too-ominous caution that the guitar would need “some finish work.” But the center strip was clearly branded “WM. G. STAHL/MAKER/MILWAUKEE” (a lie, since the guitar was made in Chicago by the Larson brothers) and 95 percent of the instrument was there.

I asked the seller a few pointed questions, made a reasonable offer, and PayPaled him the money. Four days later the UPS man delivered a big box that I ripped into with, I admit, adolescent gusto.

At this point in the typical restoration epic, buyer’s remorse sets in. What have I gotten myself into? the new owner asks. But I wasn’t in the least bothered by the Stahl’s condition — not at first. The seller had been reasonably honest — everything he said was wrong was wrong — but with each careful inspection I noticed flaws he’d failed to mention. The fingerboard extension was bent — not broken, thank goodness, but obviously sigogglin — the bridge (which anchors the strings to the body) wasn’t a correct Larson brothers’ flattened pyramid type and it was glued in the wrong location, the peghead overlay was damaged, the frets needed attention, binding was missing at the bottom of the fingerboard, the 3-on-plate Kluson knockoff tuners were flat-out annoying — and worst of all, some idiot with a paint roller had applied two gallons of runny gloppy gooey polyurethane or other superfluous substance to the guitar’s body, the front, back and sides. And that didn’t include earlier overspray of shellac, lacquer and varnish that had melted into the polyurethane — a deal-breaker for any vintage guitar collector, since original finishes are necessary to produce the instrument’s authentic sound.

Collectors argue endlessly about original finishes vs. restored. You’ve probably seen those Picker guys on the History Channel who love “rusty gold” and “the look” or the erudite appraiser on Antiques Roadshow who says, “In original condition this Philadelphia dressing table would be worth half a million dollars but since you refinished it, it’s worth seventy-five bucks. Maybe.” And that’s how it is with vintage guitars. But I’m not a vintage guitar collector. I simply wanted to play the guitar, and to do that I needed to have the polyurethane removed.

Poly finishes dampen sound and I had a lot of it on the Stahl, which meant that the guitar had reached a point in its checkered life where it was up or out. I might have relisted it on an auction site and gotten my money back, but I was determined not to sell or trash my latest acquisition. I was in possession of a rare Larson brothers Stahl Style 6 serial number 27022 (a numeral not based on production numbers), which meant the instrument was 100 years old! Who knows where it had been and the stories it could tell? Guitars, like their owners, have their own DNA and quirky personalities.

How valuable are Larson instruments? Consider this: A 1937 Larson-built Euphonon dreadnought recently listed on the Reverb for $64,500. Ouch! (If you’re interested in Larson instruments, I suggest you read The Larson Brothers’ Creations, by Robert Carl Hartman, or John Thomas’ excellent article in issue #15 of Fretboard Journal.)

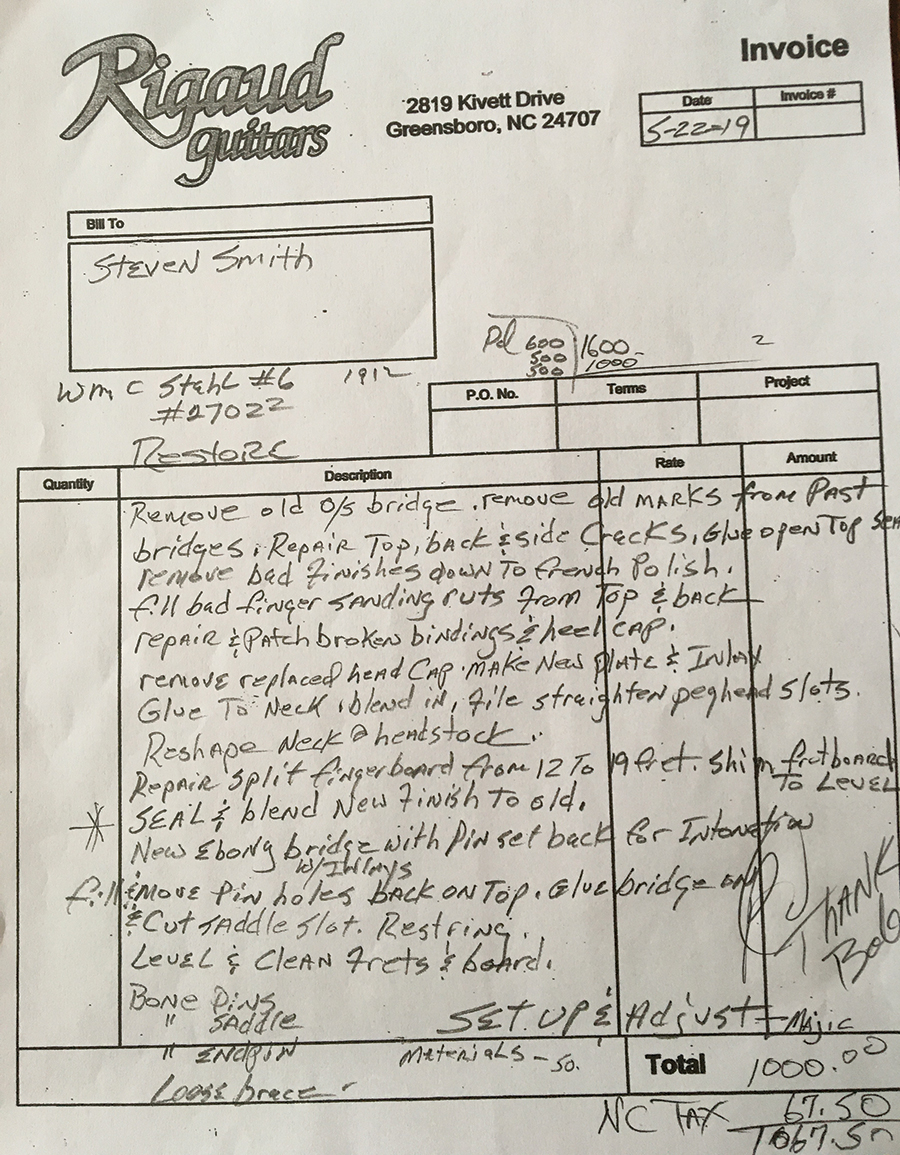

What I needed was someone — the right someone — to save my Stahl Style 6. I’d heard that it’s possible, under unique circumstances, to remove a secondary finish while preserving the original surface. I got on the phone and chatted with luthiers in Wilmington, the Raleigh-Durham area, Charlotte and the Triad, and settled on Bob Rigaud (pronounced “rego”) in Greensboro.

Bob is a world-class builder, a luthier whose guitars are comparable to those of the Larsons. Seven years ago, he built for me a New Moon koa tenor ukulele, a high-quality, handmade instrument that sings with a surprisingly mellow, resonant voice, and he’s supplied instruments for many A-list performers, most recently Graham Nash, who travels with his Rigaud parlor guitar and uses it to compose new music.

More important, Bob has a reputation as a superlative repairman. A few years ago, “Steady-Rollin” Bob Margolin, Muddy Waters’ longtime sideman, stopped in Bob’s shop to have an old Gibson L-00 repaired. I was curious about Margolin’s experience with Bob, so I emailed him. He replied: “Bob fixed my mid-’30s Gibson L-00. He checked it out and knew exactly what to do. He told me the guitar would come back better than I could imagine and it did. Big admiration for Bob.” Margolin was so impressed with the sound of his Gibson, he went directly to a studio and recorded the CD This Guitar and Tonight, a ragged, in-your-face acoustic outing in which the old L-00 vibrates like the blues bucket it is.

Bob had also repaired two of my guitars, one a Larson-built student-grade Maurer that required delicate finish work, which he accomplished flawlessly. He also sealed multiple cracks, back and front, and made them disappear. Better yet, he left most of the original French polish intact.

So in late May I drove to Greensboro and handed my Stahl to Bob. He was busily at work on three new guitars — always his first passion — but his face brightened as his eyes ran over the damage wrought on my Larson by time and abuse.

“I can fix this,” Bob said. “I can make it sing again.”

Bob Rigaud is possessed of a gregariousness purely borne of enthusiasm. His life is guitars, and he delights in every aspect of building and repairing instruments and hearing them sing. We sat in his modest workshop and talked for two hours. His hands fluttered like birdwings as he pointed out myriad flaws I’d failed to notice and explained in detail how he’d approach correcting each imperfection.

“Can you fix the finish problems and make the washboarding and back cracks disappear?” I asked.

He was uncharacteristically succinct. “I can,” he said, smiling.

The Stahl was in his hands.

Brimming with faith and high hopes, I drove back to Southern Pines and waited. And waited. June came and went. On the last Saturday in July, I traveled from High Point to Bob’s workshop to check out the progress he’d made on my guitar. The old Stahl was laid out like a cadaver on his workbench, the fingerboard taped off. And miracle of miracles, most of the poly finish had been removed and much of the original French polish seemed to be intact. The washboarding was gone without a trace, as were the many back cracks and a small hole I’d somehow overlooked. The once-mangled Brazilian rosewood back had been restored to its original glory.

“How did you repair the back so perfectly?” I asked.

“I flattened the wood and sealed the cracks with an epoxy I tinted with rosewood sawdust.”

But there was still much work to complete, including the peghead overlay, the replacement bridge, and the angle problems with the fingerboard extension. I left satisfied but anxious to have the Stahl back home.

August, September, October and November passed, and I was content to have Bob work at his own speed. But in early December, my friend Craig Fuller of Pure Prairie League and Little Feat fame drove me to Bob’s workshop. Bob, always the perfect host, showed us the guitars he was building, and Craig and I examined the Stahl in detail. It was close to being complete: a new, handcrafted bridge with inlays was temporarily applied, a beautiful peghead overlay was in place, and new Stewmac Golden Age reproduction tuners were installed, but the frets still needed work and touch-up finishing was left to accomplish. I’d hoped that Craig, who’s played more guitars better than I ever will, might try out the completed Stahl and give me his opinion, but Bob was still struggling to correct the intonation, the key to ensuring that a guitar sounds as good as it possibly can.

“I’ve never repaired a Larson guitar that had the correct intonation,” Bob observed.

On January 22, 2020 my phone rang; the Stahl was ready for me to take possession. “I’m proud of it,” Bob said.

I stepped into his workshop at 9:30 the following morning. And there it was, my 1920 Larson brothers Stahl Style 6 guitar resurrected. I picked it up, strummed a fat G chord and felt an instant synaptic connection: I remembered the sweet sound — the sustain, the purity of voice — that had amazed me all those years before. It played like silk and chimed like a chorus of seraphim. It had the mojo and “the look.” Bob smiled but said nothing. He didn’t need to. He absolutely understood how I felt. He was feeling it too.

“I loved working on this guitar,” Bob said. “When I was regluing the internal braces — which, by the way, are all maple, not spruce — I could see evidence of August Larson’s work, and I felt like I was having a conversation with him all these years later. A hundred years from now maybe some other luthier working on this guitar will be having a conversation with me.”

“You don’t have to reveal any trade secrets,” I said, “but how did you save so much of the original finish?”

“Sense of smell,” Bob explained. “As I take down the finishes, I can smell them and after all these years of working on guitars, I can pretty much tell you what the finish is and when it was applied. When I got to the French polish, it gave off a very distinct smell. That’s when I stopped.”

Great luthiers are the real guitar heroes.

I play the Stahl every day now. It’s my musical soul mate. I know I’ll never be a great musician. And that’s fine. The process of learning guitar continues to unfold for me. I like it that way.

Was resurrecting the Stahl worth the time, money and effort? Was it merely an attempt to recapture my youth? What I can tell you is that my Larson guitar testifies that a tradition honored 100 years ago is adhered to still with patience and pride. I’ll be passing the Stahl along someday, and isn’t the past always present in the hope we have in the future?

My Stahl Style 6 sits in my guitar room next to a Liberty Tree guitar made from the wood of the tulip poplar I sat under on St. John’s campus all those years ago. Hurricane Floyd roared through Annapolis in 1999 and fatally damaged the 400-year-old tree. Taylor guitars purchased the wood and built 400 fancy instruments. It’s strikes me as wholly appropriate that my Stahl and the Liberty Tree sit side by side.

After all, something so complete has a beauty all its own. OH

Stephen E. Smith is a retired professor and the author of seven books of poetry and prose. He’s the recipient of the Poetry Northwest Young Poet’s Prize, the Zoe Kincaid Brockman Prize for poetry and four North Carolina Press Awards.