Play to Learn, Learn to Play

A mother’s lasting legacy at the Miriam P. Brenner Children’s Museum

By Ross Howell Jr.

In the Miriam P. Brenner Children’s Museum, Frank Brenner and I make our way along “Main Street,” a play exhibit where murmuring gaggles of kids, parents and grandparents are scattered.

Some are sitting on kid-sized furniture, others crouching on the floor arranging big wooden blocks of various shapes.

We watch a toddler make her way up steps to an airplane cockpit with a yellow slide. She zips down to floor level, giggling.

Just down the “street,” a boy asks his mother what she’d like on her pizza.

“Mushrooms,” Mom answers.

Her son proudly takes a couple sliced-mushroom replicas from a bin to add to his creation, now ready for the tiny “oven” in the kid-sized “pizzeria” where he’s playing.

You get the idea. The children’s museum is a place for hands-on, experiential learning.

And it’s just plain fun.

Brenner and I continue through the doors of a real kitchen with big appliances and wide aluminum sinks to a meeting room with a wall of windows looking out onto Church Street and the Greensboro Public Library.

“Honestly, I didn’t know what an asset this place was until I brought my two-year-old granddaughter in here,” Brenner says. He describes watching his grandchild happily push her kid-sized cart along the aisles of the little grocery store on Main Street.

“That was the eye-opening moment for me,” Brenner says.

And it turned out to be a major moment for area kids.

The initiative for establishing a local children’s museum came from the late Jerry Hyman, a successful businessman born and raised in Greensboro, the son of Jewish immigrants from Hungary and Lithuania.

“Everybody called him ‘Pop,’” says his son, Mark Hyman, who practiced dentistry in Greensboro for 32 years and now lectures nationally on the business of running successful dental practices.

“Pop saw children’s museums in San Francisco and other U.S. cities, and wanted to create one in Greensboro,” Hyman recalls. “But people told him it wouldn’t work.”

Undaunted, Hyman called on the late Cynthia Doyle, a local legend in civic duty, volunteerism and nonprofit fundraising.

“She told Pop to come back in six months,” Hyman says.

Doyle reached out to a network of individuals from the Leadership Greensboro Program. They would go on to serve as the steering committee for a children’s museum capital campaign, led by Doyle. Three years later, in 1999, the Greensboro Children’s Museum opened its doors at 220 North Church Street, recognizing Jerry Hyman as cofounder.

“Pop wanted a downtown location so the museum would be accessible to children from all walks of life,” Hyman continues. “I know he would feel great joy at seeing all the kids playing together there.”

Hyman enjoys going to the museum to sit near a piece of art by Paul Rousso, an internationally acclaimed artist who grew up in Charlotte. The colorful installation, A Piece for Pop, incorporates drawings from each of Jerry Hyman’s children in its composition.

“I see going to the children’s museum as a way to visit with my Dad,” Hyman concludes. “He would always talk about the responsibility of giving back to a community.”

A decade after the children’s museum first opened, chef, author and restauranteur Alice Waters, founder of Chez Panisse, a Berkeley, California eatery famous for its role in the farm-to-table movement, came to Greensboro for the grand opening of the Edible Schoolyard at the children’s museum.

The Edible Schoolyard is a half-acre organic teaching garden and kitchen classroom where kids, families and teachers can learn about growing, cooking and sharing fresh, delicious food. In its ecosystem of plants and animals, the garden features vegetables, herbs, fruits, flowers, trees and shrubs, as well as worms, pollinators and most recently — a flock of chickens.

In 2015, the children’s museum launched its “Reaching Greater Heights” expansion project. The first installation was an outdoor play plaza that offers a challenging level of problem solving, teaching children how to go from point A to point B with no specified path.

Talk about heights! The plaza includes two European-imported 30-foot-tall Neptune XXL climbers connected by a 25-foot suspended net tunnel. The net and rope structures allow for family members to keep an eye on their kids while they’re playing.

“The kids aren’t scared,” says marketing manager Jessica Clifford, who’s taking me on a tour. “But many of the parents are!”

Clifford has already shown me other features on Main Street, like the post office and theater, and a real police car, plus a Volvo big rig truck, EMT vehicle, and postal van that kids can play with interactively. And she’s introduced me to the hens in the Edible Schoolyard flock.

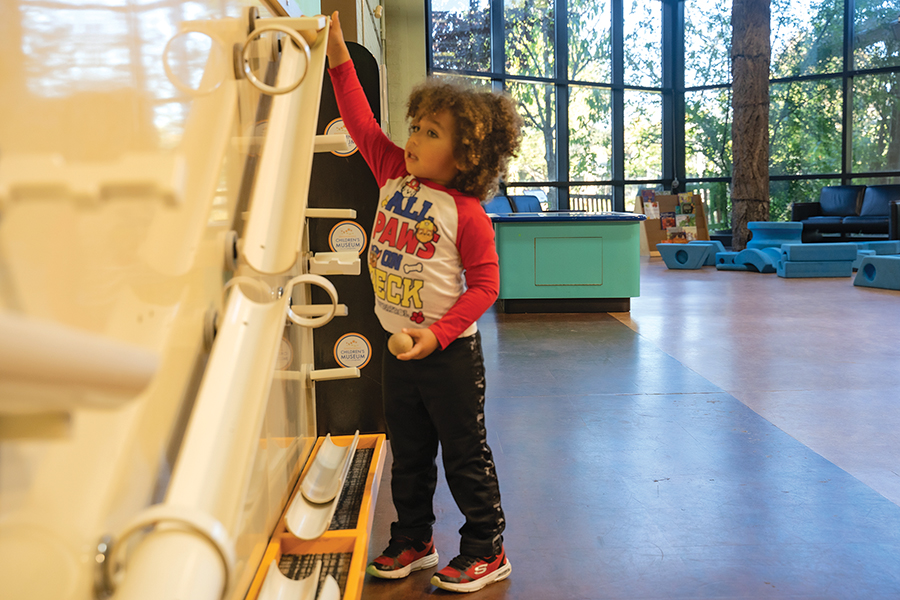

Now we’re having a look at new indoor installations comprising a hands-on water exhibit — what child doesn’t like to play in the water, right? — and a technology exhibit called “The Growing Place.” These new features add to the museum’s STEAM-based activities, which promote the idea that Science, Technology, Engineering, Art and Math can all work together to help children learn to be critical thinkers, problem solvers and innovators.

“When you think about it,” Clifford muses, “there are very few spaces in the world just for children. We adults lose our excitement, but when you come in here, you see the awe in kids’ faces.”

She explains that the feeling is contagious, that you’ll see parents and grandparents transported, acting like kids themselves.

“We bring out the kid in everyone,” Clifford laughs. “You’ll see on the wall out front, it says ‘For children from zero to 99.’”

But at age 22, the children’s museum had hit the proverbial bumpy road. Although it now had generations of enthusiasts, the roof of the 37,000-square-foot museum was leaking and its HVAC system often failed. Those kinds of expensive repairs are beyond the maintenance budget allocations most any nonprofit organization can afford and are not the kind of thing private donors feel especially inclined to fund.

“We couldn’t deliver programming the way we should if we’re worried about the roof leaking, right? Or keeping the building cool or warm?” says Joe Rieke, director of advancement and community.

“We couldn’t focus on education, on interaction, on fun, on play for children and parents when we can’t keep them comfortable, right?” Rieke adds.

Which brings us back to that major moment for Greensboro kids.

Frank Brenner’s father was Winston-Salem philanthropist “Abe” Brenner — as in Brenner Children’s Hospital in Winston-Salem or 1 Abe Brenner Place, the address of the Steven Tanger Center for the Performing Arts in Greensboro, close by the children’s museum.

So Frank knows something about giving back to a community.

“I had been looking to do something in memory of my mother, to honor her,” Brenner says. “She had a tough childhood.”

Born Miriam Prystowsky in Charleston, South Carolina, Brenner’s mother was the youngest of four sisters in a family facing difficult challenges.

“But it was certainly a happy childhood for all of us,” continues Brenner, the third of Abe and Miriam’s four children. “There were lessons they taught us really early,” he adds. “The difference between right and wrong, and the importance of education.”

Through his good friend, Mark Hyman, Brenner had heard about the children’s museum. Later, he received a phone call from Marian King, CEO of the children’s museum. King is a Greensboro native and, like Brenner, a graduate of UNC Chapel Hill.

“She said, ‘Frank, I’d like to speak with you about what’s going on at the museum,’” Brenner says. “It was good timing.”

After he met with King, Brenner sat down at home with his wife, Nancy.

He explained the needs of the museum, and said, “You know what? Maybe this is the opportunity to do something for my mother.” His wife agreed, and the next day Brenner called King to let her know their decision.

“And it’s all come to fruition,” Brenner adds.

Frank and Nancy made a gift of $1.25 million, the largest single donation the museum has ever received. It was the lead gift in a capital campaign that will reach its goal of just more than $2 million this month.

“The museum is an incredible asset to Greensboro,” Brenner continues. “I believe a place like this would’ve been transformational for my mother when she was a girl.”

So the children’s museum roof and HVAC have been upgraded. Brenner’s family participated in a ribbon-cutting reopening ceremony in October 2022, when the museum was officially renamed and rebranded.

And generations of playing kids and families will now see the name of Miriam P. Brenner, a caring mother, who would have been gratified to have her legacy contribute to the enrichment and happiness of children.

When I ask Brenner about the future, he talks about adding financial programs to make the museum accessible to all kids. While membership scholarships, discounted admissions and provisional free passes can sometimes be made available, Brenner hopes to achieve even more.

Already he’s contacted his cousin, Hal Kaplan, executive chairman of Kaplan Early Learning Company in Raleigh. Kaplan wrote the children’s museum a check for $25,000.

Kaplan told Brenner, “Frank, I want this used for scholarships for kids that can’t afford to get in there.”

“And I’m not going anywhere,” Brenner says. “I love Greensboro. My friends are here and I have grandkids here. And I must admit, I’m a little addicted to Carolina basketball, so I like to be here during basketball season. Greensboro’s home. My mother’s name is on the museum now and I want it to be the lasting, positive place it is for decades to come.” OH

Ross Howell Jr. is a contributing writer to O.Henry. He’s working on a new historical novel about a group of World War I veterans.