Our Christmas Sing

A tradition that measures the years

By Margaret Maron • Illustrations by Laurel Holden

John thought it was probably the Christmas of 1978.

John thought it was probably the Christmas of 1978.

Scott said, “No, I think it was earlier.”

“Maybe 1976?” asked Celeste.

Carlette thought that sounded about right.

After hearing them puzzle over when it all began, I finally went through some of my old journals and found this entry: “First time all five Honeycutts here for dinner since the summer. By candlelight, firelight, and tree lights, we sang carols till midnight.”

It was December 23, 1977.

As farm girls growing up amid the tobacco fields of Johnston County, Sue Honeycutt and I had sung in our church choir. I can carry a tune as long as it is pitched no higher than B♭, but Sue’s voice soared like an angel’s.

After school and marriage, we were separated first by an ocean and then hundreds of land miles, yet we kept in touch; and once my husband and I moved down to the family farm where I grew up, the friendship became even stronger.

There were eight of us that first Christmas: Sue and her husband, Carl, had two nearly-grown daughters and a teenage son; my husband and I had a 13-year-old boy. That evening together had been so much fun that we did it again the following December.

Do something twice in the South and it immediately becomes a tradition. The first three or four years, our ritual was to sing every seasonal song we could remember, from “Silent Night” to “Silver Bells” to “I Saw Mommy Kissing Santa Claus,” followed by a sit-down dinner, and ending in an exchange of gifts. We eventually scrapped the gift exchange — boring and too time-consuming. Instead, everyone is now encouraged to perform a party piece.

This might be a dramatic scene from a school play, an original comic skit with hand puppets, an operatic aria by a granddaughter who has inherited Sue’s voice, or a Christmas poem. (I have to be restrained from reading A.A. Milne’s “King John’s Christmas” every year.) Early on, our sons made us laugh with their take on the classic “Who’s On First?” routine. This past year, Sue’s 6-year-old great-granddaughter donned a blue shawl and shyly mimed “Mary, Did You Know?” When her father was that age, he came with a stash of Christmas riddles: “What do snowmen eat for breakfast? Frosted Flakes, of course.”

Getting measured soon became another part of the tradition. One end of our kitchen wall is thick with dated lines that mark the years. Off come the shoes and everyone who’s still growing stands up straight, heels against the baseboard. A granddaughter will proudly announce that she’s grown two full inches since last year, while her cousin is delighted to see that he’s almost as tall as his uncle was when that uncle was 10 years old. Sue and Carl’s newest great-grandchild went on the wall this past Christmas. She was only six weeks old and her daddy had to straighten out her little frog legs to get an approximate measure.

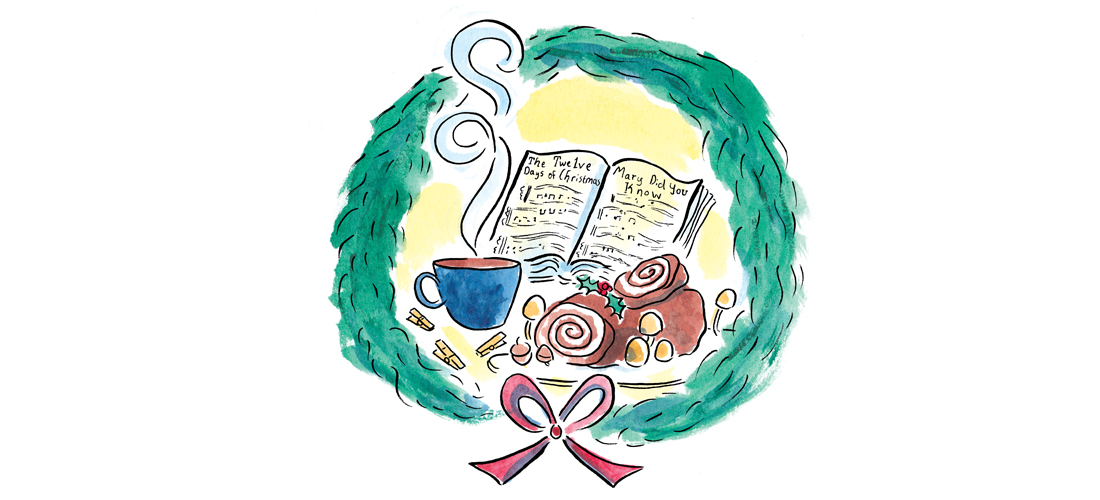

For several years, as people began to put on coats and hats and look for their car keys, the evening would wind down with a child’s whisper, “Is it time to get silly yet?” I would nod and slip her a handful of clothespins, which she quickly shared with equally mischievous cousins. Looking like innocent angels, they maneuvered among their elders, surreptitiously clipping a clothespin on the back of an uncle’s shirt, a grandparent’s sleeve, the hem of an aunt’s skirt. Soon everyone would be laughing and slapping their clothes to find the clothespin, which they immediately transferred to someone else’s scarf or hat. More than one clothespin went home on the coattail of an unsuspecting victim.

There are 26 of us now and our sit-down dinner has devolved into little plates of finger foods. The meal still ends with coffee and a Yule log elaborately decorated with meringue mushrooms, but I’ve passed the recipe on to our older granddaughter.

Some songs are dropped as new ones are added, but we’ll never drop “The Twelve Days of Christmas.” Everyone joins in on all the words except for the “gift” itself, which becomes a solo or duet, depending on how many people are here. Early on, Carl croaked out “two turtledoves” in a distinctly tone-deaf baritone, which so cracked us up that he was awarded permanent possession of the second day. With her beautiful voice, Sue was a natural for “five golden rings.” The rest of us split up the remaining days in no particular order, although my husband is rather fond of “three French hens.”

Carl left us last year and his pitch-perfect son inherited those two turtledoves. It breaks our hearts to know that this year someone else will have to sing Sue’s five golden rings. It will be a bittersweet continuation and more than one pair of eyes will glisten in the candlelight.

But laughter has always been a huge part of our tradition, too. As the first generation of grandchildren matured, their slapstick silliness faded away, but two of Sue and Carl’s great-grandchildren are now 10 and 7.

I think it’s time to slip them some clothespins. OH

A native Tar Heel, Margaret Maron has written more than 30 novels and dozens of short stories. She was inducted into the North Carolina Literary Hall of Fame in 2016.