Taking Root

The richness of autumn’s bounty finds a home in a humble root cellar

By Cheryl Capaldo Traylor

Each year when the leaves turn yellow, orange and brown, then float down to ever-growing piles and the comforting scent of woodstove smoke fills the air, I’m reminded of the stark beauty of this darkening season. It’s not quite winter, and yet Mother Nature’s crisp breath chills my neck each time her wind lifts my scarf. Gardeners can smell the acrid miasma of frost-burnt plants as the land enters its longest season of rest. These sensory experiences transport me back through the years to a place where winter arrived early, and by November the land was already blanketed in a layer of snow. Summer long gone, no more running barefoot through the dewy lawn taking coffee to Daddy as he worked in our big vegetable garden. No more homegrown tomatoes eaten straight from the vine. But summer’s harvest was always carried into the following seasons through canning, drying and preserving.

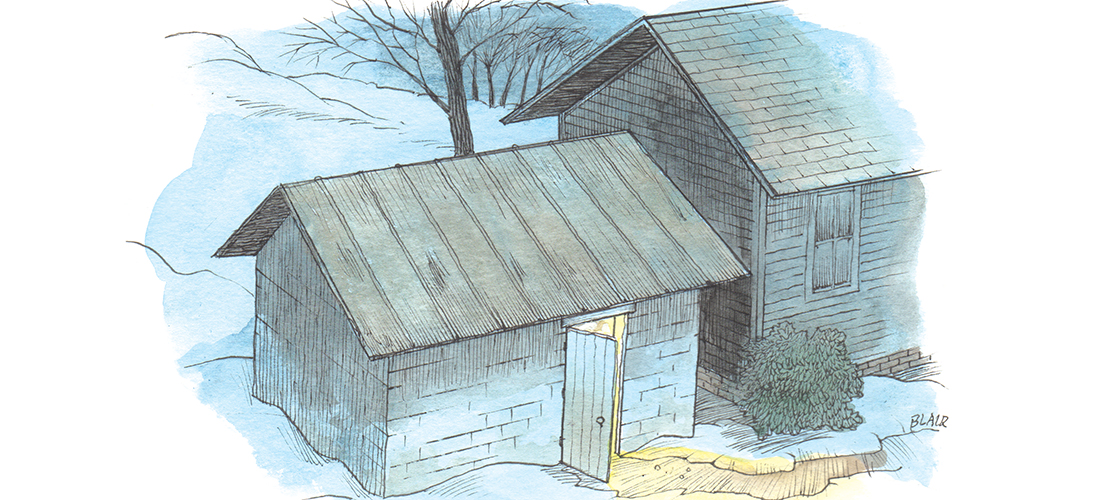

Growing up we had a two-room cinderblock building we dubbed “the Washroom” that stood an arm’s length from our white clapboard house. Dad kept his tools in the Washroom’s larger room where he tinkered, built and repaired all sorts of things. A small plastic 3-D image of Christ’s head hung on the heavy wooden door; his pale blue eyes followed me as I followed Dad around the room. The temperature dipped as you stepped down from the concrete floor of the main room into the smaller room — the root cellar. There were no windows. You had to reach up and fumble in the dark to find the light chain that hung from the ceiling. The floor was hard-packed earth, and wooden shelves covered three of the walls.

Countless jars full of fruits and vegetables in a rainbow of colors adorned the shelves: fruit preserves, tomato sauce, peppers, corn, beets, blackberries, applesauce and apple butter, jellies and homemade wine. One jar both fascinated and repulsed me: pickled pigs’ feet. Where did this oddity come from? We didn’t have pigs, so I can only guess it was a gift. People often shared what they had preserved with their neighbors. To the right of the cellar door there was a bin that resembled an animal stall where potatoes lay completely buried in a mix of sawdust and dirt. Onions rested nearby in a separate slot. Braids of garlic dangled from the rafters. For a man who worked on highway construction, money could get tight in the winter and a root cellar was almost a necessity.

As a child, I didn’t appreciate this food grown and preserved literally by the sweat of my parents’ brows. But as an adult who hasn’t the time, talent or space to preserve my own food, I now understand the work involved. I tried canning tomatoes once as a young bride. It ended in disaster. My husband came home to find a blood-red ceiling and splattered countertops that looked like a scene from a horror movie. Every jar of tomatoes had burst open. I underestimated how important temperature and capacity were when canning. Preserving is an art form and takes practice. Afterward, Mom wanted to teach me, but I got caught up in life and caring for my own little family. I assumed there would be plenty of time to learn from her in the future.

I am humbled by my parents’ sacrifice. Dad spent weeknights after work, and all day on weekends, in the garden during growing season. The intense summer sun turned his Italian skin into brown leather. Mom spent day after day in an unairconditioned kitchen, standing over a Hotpoint stove while the sweltering steam from canning pots fogged up the windows. Because they had four small mouths to feed and not a whole lot of money with which to do it, they worked together. And though many meals were modest — brown beans and biscuits made with water instead of cream; potato-onion soup; chopped bologna instead of meatballs in tomato sauce; or garlic-and-dandelion-greens salad — there was always something out in the root cellar that Mom could turn into a good meal.

Sometimes these memories arise and take me by surprise. In a way they make me feel fortunate to have grown up in a home that often knew lean times, yet never knew lack. And although West Virginia winters were bitter cold outside, inside we were warm. The stove glowed as Mom prepared something from those old Mason jars filled with homemade love from the root cellar. OH

Cheryl Capaldo Traylor is a writer, gardener, reader, and hiker. She blogs at Giving Voice to My Astonishment (www.cherylcapaldotraylor.com).