Posing for Daingerfield

Up in Blowing Rock, the spirit of a prolific painter still resides at Edgewood Cottage

By Ross Howell Jr.

On a mild evening in Blowing Rock, where I spend the hottest days of summer, a nice place to rest is on a bench next to the bronze statue of artist Elliott Daingerfield. When you sit down, the effect is quickly apparent: You’re posing for the artist.

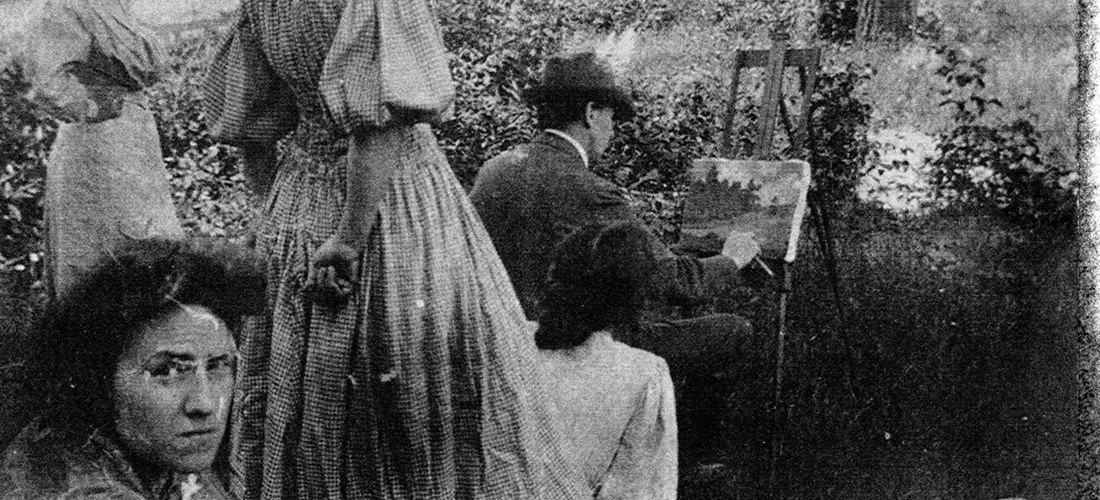

Daingerfield peers intently at you over his bronze easel, unruly hair swept back from his forehead, palette in one hand and brush in the other. He’s painting outdoors, en plein air, as he often did in life.

A short distance behind Daingerfield’s figure sits Edgewood Cottage, his first residence and studio in Blowing Rock. Designed by the artist and completed in 1890, the building was recently restored.

Daingerfield — the youngest of six children — was born in Virginia in 1859 but grew up in Fayetteville, North Carolina, where his father served as commander of the Confederate arsenal. According to family tradition, when his older brother, Archie, gave him a box of watercolors one Christmas, he immediately began painting beautiful pictures.

Young Daingerfield would go on to study with a local china painter and apprentice under a Fayetteville photographer, where he learned not only how to make pictures, but also to tint them by hand.

In 1880, at the age of 21, Daingerfield left Fayetteville to pursue a career in New York City. There he would become apprenticed to Walter Satterlee, an associate member of the National Academy of Design and a respected teacher of art. Satterlee would make Daingerfield an instructor in his still-life class, the young man’s first teaching position.

Daingerfield was determined and prolific. Within a year he saw his own work exhibited at the National Academy of Design. In 1884, he left Satterlee and moved to Holbein Studios, where he would paint alongside artist George Inness, who became a life-long friend.

In the winter of 1885-1886, Daingerfield suffered a severe case of diphtheria. The following summer, seeking the curative powers of mountain air, he returned to North Carolina.

Arriving in Blowing Rock after an arduous wagon ride along a rutted, dirt road snaking up the mountain, Daingerfield encountered chickens, pigs and other livestock in the streets. But rising beyond the town was Grandfather Mountain, the highest peak of the eastern escarpment of the Blue Ridge Mountains. The lore and legend of the town and the mountain spoke profoundly to Daingerfield’s spirit. He would keep summer homes in Blowing Rock until his death in 1932. Daingerfield taught summer visitors and others vacationing from the Art Students League in New York or the Philadelphia School of Design for Women, where Daingerfield taught in winter.

Daingerfield was “an advocate for women artists during a time when they were denied the privileges of their male counterparts,” says Kadie Dean, lead docent of the Blowing Rock Art and History Museum and chair of the Artists in Residence at Edgewood Cottage.

Now more than a decade old, the summer residency “continues to build on Daingerfield’s legacy of supporting artists,” Dean adds.

This summer’s program includes painters, quilters, photographers, leather artisans, pottery makers, mixed media artists and woodworkers — most from the High Country. Visitors can watch the artists at work in Edgewood Cottage and purchase pieces of their art right on site, which is currently open to the public only during this annual residency.

In the past, a portion of sales proceeds has been donated to various charities. But this summer, half the net proceeds will be used for a very special purpose: to upgrade Edgewood Cottage and open it to the public as a museum.

Fittingly, the cottage’s first public exhibition “will be centered around Elliott Daingerfield,” says Blowing Rock Historical Society president Tom O’Brien.

Modest Edgewood Cottage was replaced by a larger residence, Windwood, completed in 1900. Daingerfield’s grand manor Westglow, built in the Greek Revival-style on land overlooking Grandfather Mountain, was finished in 1917.

As an artist, Daingerfield is hard to categorize. Some historians view him as a religious painter, and many of his works decorate church altars and chancels. Others describe him as an Impressionist, since many of his canvases demonstrate the tonality of the landscapes of his friend, George Inness. Some see Daingerfield’s paintings of rural mountain people in the tradition of Jean-François Millet, whose realism celebrated peasant life in France. Others view Daingerfield as a visionary, painting ethereal goddesses in the natural world to suggest its spiritual essence.

Historians agree that Daingerfield’s work is suffused with mysterious, ineffable beauty.

So if you find yourself some twilight evening sitting on the bench by Daingerfield’s statue, you might imagine for a moment that you saw a lock of the artist’s hair lifted by the breeze. Or be certain the tip of his brush just moved.

And maybe it did. OH

Ross Howell Jr. is a freelance writer in Greensboro. Contact him at ross.howell1@gmail.com.

The 2021 summer Artists in Residence at Edgewood Cottage in Blowing Rock opened May 29 and runs through September 19. Featured artists change each week, so be sure to check the schedule for artists and times. Info: artistsatedgewood.org

Photographs Courtesy of Blowing Rock Historical Society