Andy Zimmerman’s and ArtsGreensboro’s

mini-folk fest on Lewis Street

By Grant Britt

Crossing the barrier is a leap of faith. Marked with flashing red lights, clanging bells and a metal arm that bars your way, it divides the town. Historically and metaphorically, crossing the tracks means going from a prosperous part of town to an economically deprived one. But if Andy Zimmerman has his way, the railroad crossing that separates his West Lewis Street empire from the rest of downtown Greensboro will no longer be a barrier, but a gateway for the Lewis street homesteaders he calls “the creative class on the other side of the tracks.”

If you haven’t ventured down to lower South Elm in the past year, you won’t recognize it. Not too long ago, Lewis Street looked like a slum, the buildings shabby, derelicts leaning drunkenly on one another, barely able to keep from collapsing in the street. Zimmerman’s interest was piqued two and a half years ago after he had just sold off a string of watercentric businesses including Confluence Water Sports, Wilderness Systems and Legacy Paddlesports when a friend asked his advice about buying the building at 117 West Lewis, formerly an antique shop. But Zimmerman’s friend only wanted advice. “And I said, ‘Do you mind if I buy it, ’cause I like it.’ It was just, ah, I don’t have anything to do, let me buy this building,” Zimmerman adds, breaking into a laugh. He hung out a sign hoping to entice entrepreneurs to put up a restaurant or bar in the space and a month later signed a deal with Gibbs Brewing Company. Greensboro Distilling Company has begun making small-batch spirits right next door. He planned to have his office in the other half of the building but two weeks later, Joey Adams, president of the board of directors of the Forge, a makers space for community hands-on craftsmen, called and explained what a makers place entailed, and an hour later they had a deal.

On a guided tour of the properties, Zimmerman is a genial host, casually dressed in shorts and a T-shirt and sandals. Everybody knows him. He can’t go ten feet without somebody wanting a word, and he deals with all of it on the fly, calling people by name, taking care of the problems with a word or two as he keeps moving. “Welcome to The Forge,” he says as we pass through the outside doors with two sledgehammers as door openers. Seconds later, we’re confronted by two big box wrenches mounted as handles on the inside doors. What was once the Flying Anvil is unrecognizable, inside and out. The raggedy chain link and barbed-wire fence around the property is gone, replaced by what Zimmerman proudly describes as “a cool, artsy-type fence.” Inside, the place has been gutted, re-imagined as a hands-on learning place for trades. “I spent too much money fixing it up,” Zimmerman admits. “But I get a different kind of return with this place; it’s really created some neat businesses job opportunities and a place for retired people, or for the unconnected, as we like to say.”

We pass one member operating a laser-engraving machine. His attitude embodies the spirit of the Forge. Asked how it’s going, the man tells Zimmerman that he’s not getting all the power he needs because of a part he’s waiting on, but “instead of moping, either I give this stuff up or get back at it, so I’m just back at it. Thank you for supporting us,” he says as Zimmerman pats him on the back and we move on.

Another Forge stalwart is Joe Tiska, head of machining, who worked at P. Lorillard for thirty-three years. When he retired, the company gave him these two enormous milling machines on which Tiska is happy to teach anybody who wants to learn more about metalworking. “Somebody wants to try welding or machine shop, they come in here,” Joe says. “Some people just come and get hooked on it.” Zimmerman points out that “this is a lot less intimidating than down at GTCC.”

The last tour stop is Zimmerman’s office, aka HQ Greensboro. “In 1898, this was Lewis [Bros.] Wagon Company, next door where my offices are, was a livery stable,” Zimmerman says. “When I bought it, it was falling down.” It’s beautifully restored, with 300-year-old pine floors salvaged from a building near Revolution Mill and two levels of twenty-five office spaces filled to capacity.

Zimmerman’s office door is camouflaged as a bookcase. Prominently displayed is the book and CD combination, We Are The Music Makers: Preserving The Soul Of America’s Music, produced by Timothy and Denise Duffy. (“I’m trying to help him market his photography,” Zimmerman says.)

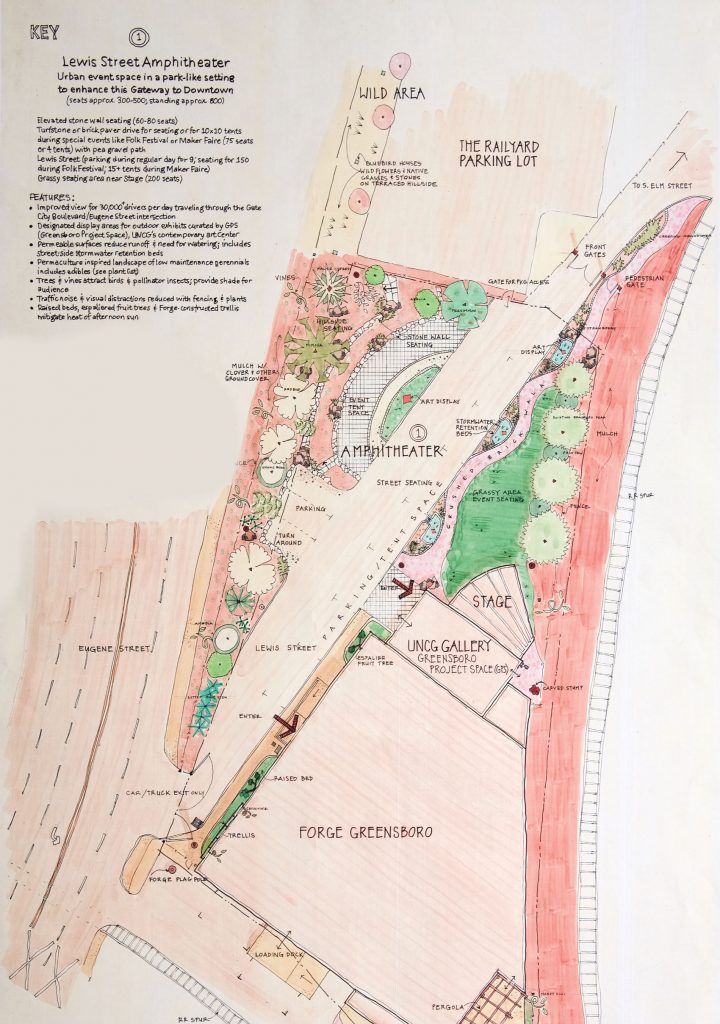

But as impressive as this place is, we’re here to discuss Zimmerman’s plans for a local stage for the National Folk Festival. Dubbed the Lewis Street Amphitheatre, the area outside the former Flying Anvil, now the Forge, features seating for 300–500 and standing room for 800. The ambitious project will debut as a stage hosting local acts during the National Folk Festival. An architect’s drawing describes the outdoor area as “an urban event space in a park-like setting to enhance this gateway to downtown.”

ArtsGreensboro President and CEO Tom Philion got together with Zimmerman to jumpstart the project. “Last year we did “Songs of Hope and Glory” with Laurelyn [Dossett] and Rhiannon [Giddens] on Thursday night as a pre-celebration event at the Railyards. Friday night, in Hamburger Square, we had doby, kind of a late-night thing outside of Natty Greene’s.” Philion describes the reaction as “fantastic, so we were thinking, what are we gonna do this year?” Philion says one of the things that became a consideration this year was how to focus on the Elm Street corridor and more specifically the South End, in terms of introducing people to all the neat stuff that’s going on down there.

But the tracks turned out to be more than just an economic barrier. “The sanctioned Folk Festival people said ‘no, there are issues with having events on the other side of the tracks,’” Zimmerman says. “One of the issues was making sure it was safe for people to cross railroad tracks. And I certainly get that, but then you say, there’s cross-gates, and there’s whistles, and there’s lights and all of that, but I’m not one to take no for an answer,” he says. “There’s gotta be a win-win situation where the loving can be spread to the other side of downtown Greensboro.”

Philion and ArtsGeeensboro jumped into the love fest. “We had a conversation with Andy Zimmerman, and thru Andy, with a lot of the merchants at that end of town, decided to do a new stage Friday night, Saturday night and Sunday late afternoon,” Philion says. “After all, it’s an activity that draws people ’cause they hear the music. Far enough off the footprint so people would have to say, ‘Hey let’s go check that out.’ Idea is to have fun and draw people to south end, introduce them to that community.”

Estimates of the crowd for the Folk Festival’s second year in town are running 130,000 or more. “It’s a community effort because we really want everybody to benefit from the festival coming to town,” Philion says. The additional local stage will run later than the Folk Festival on Friday and Saturday night. “The Folk Festival pretty much shuts down around 10 p.m.,” Philion says. “This stage will give people who aren’t done yet, who want more, to move down and see what’s going on down there in the South End.”

Zimmerman is cooking up more treats from his end as well. “We’ve got a good collection of people down here, creative, artsy-craftsy musicians, so we’re also going to be lining up our own music as well as utilizing Tom’s resources.”

“A lot of my development work downtown has been happy collisions,” Zimmerman says. “Now I’m much more calculating in my development work and planning. Once upon a time, he says his way of doing thing was ready fire, aim. “Now it’s a lot more ‘ready, aim, fire.’ But a lot of it at the beginning, it just felt good, so I did it.” OH