Fun with Moby Dick and Jane

Or not so much

By Jane Borden

Think Moby Dick is overly long, unnecessarily complicated and tedious enough to make readers question the existence of God? Congratulations! You may as well be an academic (print your own Ph.D.), because not only are you right, but that was also (mostly) the author’s intent. This is in part why fans of the novel are rabid. Rather than regarding its laborious nature as something to be endured on the way to enjoyment, they see the hardship as part of the point. Every supernerd longs to be part of a secret meta club, the more winking and clever, the better.

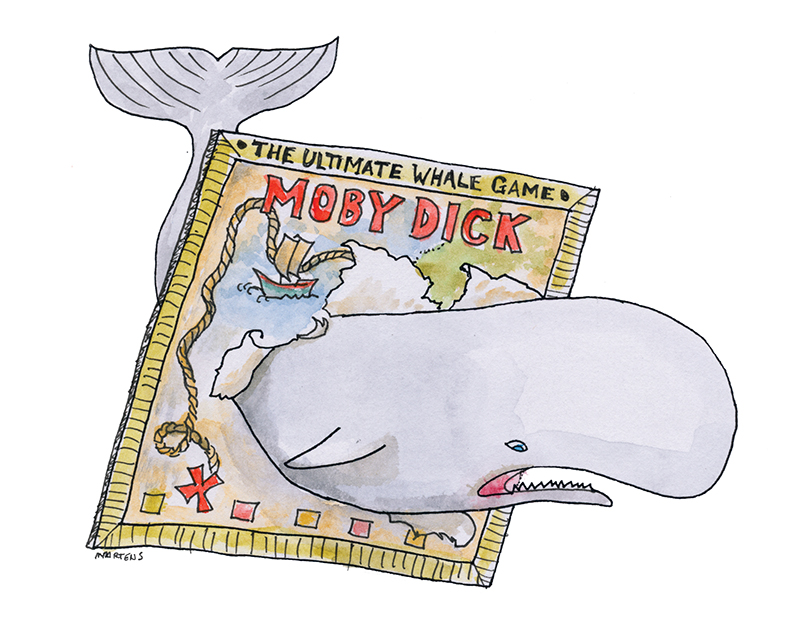

This is how, back in the early 2010s, a handful of ubersupernerds came to create a board game based on Moby Dick — a game as intentionally long, complicated and tedious as its source material. And because this is exactly the kind of literary humor my husband, Nathan, adores, he donated to the game’s Kickstarter page, which means that once the instrument of torture, I mean, game, was finally produced, we received a copy in the mail.

“Cool,” I said. Then I opened the instruction booklet and discovered it is 10 full pages — including a page of (small-text!) glossary terms. Before you can learn the rules of the game, you must adopt a lexicon? Hard pass. The game sat on a shelf for more than a year because Nathan had no one to play it with.

Finally, almost two years later, in the summer of 2015, when we rented a house in Joshua Tree with two other couples, Nathan saw his chance. There would be ample time to pass, others in our group were avid readers and I would literally be trapped in the desert. He packed “Moby Dick or, the card game”— of course, it has a referential title — in his suitcase. Almost immediately after we arrived at the Airbnb, Nathan suggested we play. Our friends were intrigued.

But then, in spite of the fact that he is employed as a teacher, it took him 20 minutes to explain the rules to our friends. I do not blame him. I do not blame our friends. And so we embarked on a great adventure that would test our strength and rattle the very scaffolds of our souls, and from which we would emerge forever changed. Which is to say, it was annoying.

Since Moby Dick is ultimately a story about revenge, then you can call me Ishmael, because the tale I’m about to relay is one of a person wishing a fate worse than death on the creators of this game. Sure, this essay is a little unfair, because I am not the target market for this game. In fact, I have never even read Moby Dick. But I have been stranded on a plane and had to sleep at an airport hotel and then wake up to take a train to rent a car, which got stuck in the snow — and I’m guessing that’s more or less the same experience.

If you are like my husband, go and buy this game. It will scratch your highbrow itches. If you are like me, Yahhhrrr, beware the depths of confusion and futility into which ye will hurtle headfirst, not unlike the sailor, in the beginning of the novel, who, while retrieving oil from a hunted whale, falls into the carcass of said whale, which then sinks into the sea. In other words, kiss your night goodbye.

You may wonder how I know that plot detail if I haven’t read the book. Ah, you’re a close reader! I scoured a plot breakdown of the novel on the Internet in order to execute the following compare-and-contrast between the novel and the experience of playing a game based on the novel, with the intention of saving you from ever having to play it yourself. Now, let’s ship out.

• While writing Moby Dick, Melville invented several words by taking existing words and changing them slightly. While we were playing the game, my friend Susanna challenged Nathan several times, “Are you just making up these rules?”

• The book is one digression after another. It’s a story about a whale hunt until, for dozens of pages, it’s instead a reference text detailing the process of hunting whales and extracting their oil. No, it’s about imperialism. Or, wait . . . boats? This is how you’ll feel while playing the game. Once you figure it out, it will change and you must learn new rules that force you to adopt new worldviews — which, come to think of it, sounds like imperialism, so that’s an interesting layer, but still, Nathan, are you making up these rules?!?

• In the book, Ahab’s ship, the Pequod, couples — or gams — with nine other ships. Each meeting is a kind of parable. The repetitiveness of the game is also a series of parables, each one telling you to get a life.

• While sailing toward the equator, the Pequod experiences a typhoon. Lightning strikes the mast and disorients the compass. There will come a time when you will also feel completely lost.

• After taking what they want from hunted animals, the crew leaves behind the whale carcasses for sharks to consume, sometimes without even untying them from the ship. While playing, you will envy the whales.

• Throughout the novel, Melville alludes to or references the Bible, Shakespeare, Homer, and various other literary, religious and cultural sources. The game also borrows elements: from card games, dice games, role-playing games, and, when you’ve reached your breaking point, Russian Roulette.

• As the book does, playing this game will also force you to question the existence of God, because how could a just and loving creator put you through this?

• Or perhaps it is judgment meted. Melville named his sea captain after this Bible verse: “Ahab did more to provoke the Lord God of Israel to anger than all the kings of Israel that were before him” (I Kings 16:33). While playing the game, you will ask yourself: What did I do to anger God?

We didn’t sit down to dinner until 10:30 p.m. It had taken four hours for us to reach the last “chapter,” after which we could finally fight the great white whale, Moby Dick. Who won? No one! That’s the point. Everyone loses. The game is a metaphor and, as such, was never actually intended to be fun. I went to bed around midnight. Have I mentioned yet that I was very pregnant?

When I waked at 6 a.m. the following morning due to a series of single-engine planes buzzing past my window on account of a meetup of the local recreational pilots’ club, I thought about something Nathan said the night before. Scholarship tends to agree that Moby Dick is a criticism of transcendentalism and, specifically, an argument against the transcendental tenet of self-reliance. Ahab is a caricature of extreme self-reliance.

Lying in bed, I certainly did not feel in control. The planes would only continue, like the incessant and inescapable waves of a typhoon on open seas. I dressed myself and entered the living room. Everyone else was also awake, having reached similar conclusions. It was the perfect morning to play “Moby Dick or, the card game.” OH

Jane Borden is a Greensboro native, who now lives in Los Angeles, where she is still playing that last round of “Moby Dick or, the card game.” Please send help.