Just in time for April Fool’s Day, our naturally funny correspondent takes a look at the past, present and future of comedy in the Gate City

By Billy Ingram • Photographs by Sam Froelich

Have you heard the one about a city that didn’t take itself too seriously, so much so that it launched many a comedic career?

Greensboro may not exactly be perceived as a hot bed of hilarity, but over the years, a lot of first-rate acts have originated in the Gate City. In fact, it is where one of the greatest comedy routines of the 20th century originated as this magazine recounted in December 2015, “What It Was, Was Football” by Andy Griffith, was recorded live at the Plantation Supper Club in 1953 and perfected at a little-known recording studio atop the original location of Moore Music Co. on Market Street. That cornpone-infused 45 disc catapulted “Deacon” Andy Griffith to superstar status, remaining to this day one of the best-selling comedy records of all time. It was influential as well, inspiring generations of comedians from Bill Cosby to Jeff Foxworthy.

Two decades later, in October of 1973, Gate City native Rick Dees rocketed all the way to No.1 on the Billboard Hot 100 chart with the novelty tune “Disco Duck.” The very next year writer Harry Ruskin wrote a book entitled Comedy Is a Serious Business. He was right and in coming years it also became big business. Beginning in the late ’70s, nightclubs featuring standup comedians began to flourish in big cities such as New York, Chicago and Los Angeles. Within a decade there were thousands of Laugh Factories, Improv Asylums, Punch Lines, and Catch a Rising Star–style rooms scattered around the country. Especially in those larger markets, club owners discovered that societal misfits with a warped worldview and an overwhelming desire to express themselves on stage could prove to be a cheap source of labor.

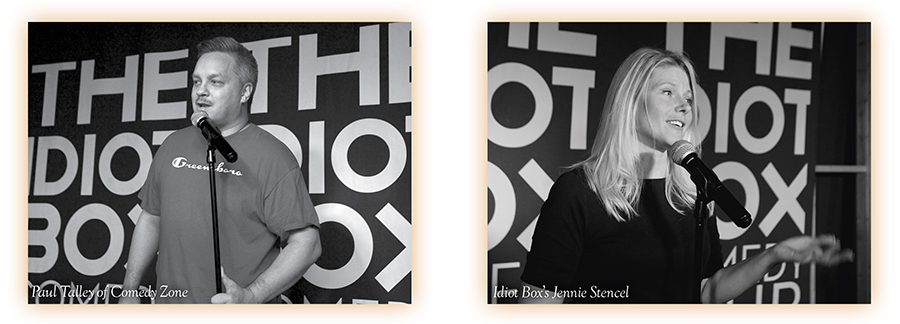

It wasn’t until 1996 that our city was blessed with a proper comedy venue. That’s when Paul Talley opened his nightclub for yuks on Holden near Spring Garden. Not that it was his plan. “Out of the blue, two guys come knocking on my door and say they were with the Comedy Zone circuit, a chain, a very loose chain, and asked if I had considered doing comedy in this vacant building I had here.” Talley was already operating Arizona Pete’s located across the parking lot. “I said, ‘Sure.’ I had no idea what I was doing,” Talley admits.

The enterprise proved a great deal more involved than owning a country-western themed dance club like Arizona Pete’s, “There’s far more management and execution needed for a comedy club,” Talley says. “You’ve got the reservations, showtimes you need to adhere to, performers have to be here on time, you’ve got hotels. . . after a year or two we kinda figured it out on the fly.”

As a chain, Comedy Zone has its own booking agent with a stable of comedians who rotated throughout its various franchises. A system with national booking agents allows Comedy Zone to host name acts like Norm MacDonald, Andrew Dice Clay, Chris Tucker and Chris Rock. “We’ve had on the bigger guys, we get them on occasion,” Talley notes. “If they want to do a smaller club on an off-night, we’ll have them once a month or so.”

Jennie Stencel is the proprietor of the city’s most intimate comedy club, The Idiot Box. After bouncing around in different locations, it appears to have found a niche on Greene Street next to craft-beer provisioner Beerthirty.

Why a comedy club? “My husband [Steven Stencel] and I performed together in Chapel Hill,” Stencel replies. “We started having children and were working for somebody else, so we took a few months off from doing comedy and thought ‘This is horrible.’ So we moved here and opened Idiot Box.”

As for their mission, “The Idiot Box exists to grow the local comedy scene,” Stencel says. “So we book a lot of locals and we do trainings and bring in national acts also. We have improv on Saturday. When we started having Open Mics, we had five or six new comics and now our Open Mic sells out a lot. We do one on Thursdays always and we do one on Friday nights sometimes.”

Comedy Zone also emphasizes homegrown humor. “We do very few national acts here, once a month maybe,” Talley says. “The price is only $10 a ticket which is insanely cheap. If you had a national act it would be 30, 40, 50 bucks. Our acts, they’re all funny as can be, they’re just not quite famous yet.”

Talley also understands the importance of priming the pump. “We do have an amateur night once a month,” he says. “We get 150, 175 people in a crowd, which is strong for a Thursday night. We do about eight to 10 locals then we put on a bigger act up there to close the show. The problem is, from a club’s perspective, it’s a little tough to make money on it.”

Comedy Zone’s amateur nights have led to some major talent rocketing to shooting star status. “Jourdain Fisher [back-to-back winner of The Ultimate Comic Challenge] started here. He’s now writing for Jimmy Fallon’s Tonight Show monologue,” Talley tells me. “Chico Bean got his start here as an amateur. He’s now very big on Wild ’N Out, the MTV show.” B-Daht (102 JAMZ’s morning show) and A&T alumnus Darren Brand, who goes by Big Baby, were also featured on Wild ’N Out.

Chemistry nightclub drag performer Heidi N Closet will join 12 other contestants on Ru Paul’s Drag Race this year. Cee-Jay Jones, Ben Jones and King David all tour extensively, each owing their careers to our comedy scene. As for some of the up-and-comers, just tune in to ROCK 92 every Friday morning to “2 Guys Named Chris.” Their presence on the airwaves, says Talley, “is tremendous for us.”

The 2 Guys Named Chris Comedy All-Stars are all Comedy Zone alums.

Chris Wiles is another well-known working comic with local ties, “I’ve been with Carnival Cruises since 2001,” Wiles tells me from somewhere in the Caribbean. “It’s been my main source of income since 2009. With multiple television appearances, including season 3 of Last Comic Standing, his way up the laughter ladder was not atypical — just get up in front of folks and start slinging jokes.

“I was a junior in high school,” says “A teenage nightclub called Islands in Winston-Salem was opening up in 1989. I went in to audition as an actor and spent about an hour with the owner and he goes, ‘Man, you’re really funny. Have you thought about doing standup?’ I said, ‘Look man, if you’re going to pay me and put me on stage I’ll do anything.’”

The owner of Islands and the high school student sat down and wrote what they thought was five minutes of the greatest standup comedy ever. “It was a really strange setup,” Wiles says of Islands. “The music would be playing, kids would be dancing, then three times a night the DJ would stop the music and go, ‘OK, it’s time for comedy’ and I would be on the stage. They’d put the light up and the kids would gather around the stage. I would do five minutes of comedy and then they’d go back to dancing and playing video games.”

Wiles was managing Dominos Pizza and Papa Johns when our Comedy Zone opened in ’96, another local comic introduced him to Paul Talley and he ended up becoming the house emcee there for the next 13 years. “I’ve got a neat following [in Greensboro]. They always show up,” Wiles says. “This Valentine’s weekend I had the fastest sellout of any of my shows. They’re from all walks of life, all ages, I’d say the average crowd is between 23 and 60 years old.”

Shared laughter unites people, at least you’d think so. Then again, it may be true what George Orwell once famously said: “Every joke is a tiny revolution.” Fifty years after Lenny Bruce tested the limits of performance art, in today’s pearl-clutching atmosphere, where scolds and trolls garner attention for themselves not by creating something but via expressing outrage over the slightest slight, what are the limits to what can and can’t be expressed in public?

“It’s much worse now than it was in 1996,” Talley says. “Before, there were just some things that were offensive. Everything now is offensive. Twenty years ago, you could tell a joke without offending people. There are certain things I tell my comics to avoid. Politics, religion — you’re gonna be funny to half the people but you’re going to piss off the other half.”

“The world is definitely different,” says Jennie Stencel of The Idiot Box. “For our improv shows, our goal is for people to come and have a night out and have fun. Nobody really wants to talk about politics. They yell it out, they think they want to hear about it, but you have to agree with everyone 100 percent now. We could be the same political party, we can mostly agree, but I like this candidate and now we’re not friends anymore!”

“We kind of figured it out,” Talley says. “Some people might say, ‘He offended me, he said this. . . ’ I thought, ‘Well, that’s reasonable.’ Everything was a surprise when it was all new.” While there’s no desire to stifle a performer, “There are certain things, certain words that, in this market, we really don’t want them to say.”

Stencel has noticed a seismic change in the national sense of humor over time. “If you go watch comedians in the ’80s,” she offers, “Famous people, the terminology that was P.C. then is just not OK now. They weren’t terrible people in the ’80s. Now they’re great people, but what you were allowed to say was different and how you said it was different as well.”

Disparate age groups even think different things are humorous. “You could have amateurs come in and make fun of millennials,” Stencel says. “Well, if it’s an audience full of millennials they’re like, [‘Ugh’]. We have a lot of young people come here to have a good time and if it’s not really funny, it’s just insults.”

Surely college campuses, those bastions to an open-minded understanding of the world writ large, would be a safe haven for the free expression of ideas. On the contrary, it’s been more than a decade since comedians like Chris Rock, Larry the Cable Guy and Jerry Seinfeld swore off doing shows on college campuses lest they find themselves buried in an avalanche of grievances from butt-hurt snowflakes.

“The college crowds have become overly sensitive,” Chis Wiles notes. “I think they forget they’re coming to a comedy show. Without tragedy there is no comedy, without conflict there is no comedy.” The last place Wiles played a college gig was Virginia Tech. “That was about six years ago and even then they were becoming a bit sensitive,” he says. “You can’t talk about homosexuality, can’t talk about race, you can barely talk about sex on a college campus which is weird because, you know, outside of going to learn something I thought that’s what college was for, sex.”

Another factor, Stencel believes, “It’s just easier to perform your comedy in a venue that’s intended for comedy.”

This level of selective outrage is a worldwide phenomenon. In 2015 almost two dozen staffers at the French humor magazine Charlie Hebdo were gunned down by religious fanatics because of a cartoon they published.

Numerous studies over several decades consistently inform us that a fear of public speaking is an American’s worst nightmare . . . more terrifying than death, financial ruin, or (shudder) clowns. Besides being an effective way to improve one’s oratory skills, I’ve been told that The Idiot Box’s weekly improvisation classes are highly entertaining. “Comedians are a fun group of people to be friends with and work with,” Jennie Stencel insists. “That part of my job is way more fun than probably a regular job. Everybody’s cool and interesting and smart.”

I myself tried standup once, back in the mid-1970s, when I convinced club owner Bill Griffin at the Hilton Underground to let me go on before the band on a Friday night. The Underground was one of those darkly lit, smoke-filled, shag-carpet-on-the-wall joints but it never occurred to me that my 17-year-old self would get heckled by one of the seven drunkards right out of a W.C. fields movie scattered about the 20 tables at 7 p.m. in the evening. As a result, my five-minute act became a minute, 45-second routine. At least the hippie musicians liked it.

Who knows, had I succeeded at standup, perhaps I’d be cruising from one tropical sandy paradise to another just like Chris Wiles. “I’ve gotten to the point now that I’m not a big fan of beaches anymore,” Wiles confesses. “I’m more about the mountains because I’ve been on every beach out there.”

That’s the punchline. Say g’night Gracie. OH

According to IMDB, Billy Ingram is an actor, producer and editor best known for “The Nathan Stringer Summer Music Show.” He’d like to think otherwise.