John Mark Hampton’s Moriah Guitars is an acoustic dream come true

By Grant Britt • Photographs by John Koob Gessner

“Let me find somewhere to sit down and kinda blow off the dust,” Moriah Guitars’ proprietor John Mark Hampton says by way of greeting when you enter his space. Hampton has a sawdust nimbus hovering over his head, surrounding him with a slightly fuzzy aura that marks him as a luthier, a hands-on creator of one-of-a-kind stringed instruments.

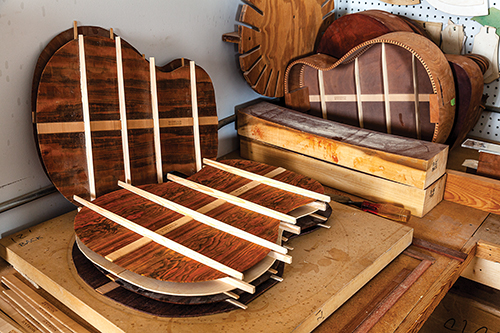

Hampton creates his magic in a warren of rooms tucked away behind a tax and accounting service in a business park near Guilford College. Enter through the tax office lobby and wander through a labyrinth of expanding spaces littered with dismembered guitar body parts and tools like Paul Bunyan’s dentist might use to extract teeth. Lurking in the back of the warehouse-sized space are hulking machines the size of printing presses, resembling cast-iron behemoths lying in wait for prey to devour.

The process here seems to be a marriage of the old and new. “My philosophy is find the best way to do it, and don’t be anti-new,” Hampton says. “There’s lots of great stuff coming out with technology, but there’s also the old way where you have to take a tree and turn it into something, you know? It’s just a lot of processes.”

The Greensboro native kicked off his luthier career while attending Wilmington College in Ohio, taking an independent study at the Guitar Research and Design Center in Vermont in 1979. Returning to Greensboro from summer vacation with some of the guitars he built while in the program, Hampton approached Keith Roscoe, owner of the Guitar Shop, a guitar-building business on Tate Street. Roscoe gave the newly minted luthier an opportunity to build something for him that summer. “He just said, ‘Here — why don’t you just go in yonder and make me some guitars?’” Hampton recalls. “And I went to the drawing board and designed ’em from scratch. I made three electrics and one bass.”

He had been playing guitar since he was 13 and loved the sound and capabilities of the instrument. He also had a knack for woodworking. “When I got up to college, I had the opportunity to do anything I wanted, and I just shot for the moon, and said ‘What can I make?’ Just started like that, kind of like a dream to do it.”

Hampton was working for Roscoe, designing and building guitars when Ken Hoover started working there as well. Within a year, the two had left to start their own company, Zion Guitars, in 1980. “Ken and I just loved working together, and the chemistry was just really there,” Hampton says. “Bear in mind, I’m 62 now, and I was only 22, and Ken looked over at me one day and said, ‘How would you like to start a business?’ And I looked and him and said, ‘Uhhh . . . what do you mean?’ We just started off really from scratch, flying by the seat of our pants,” Hampton says, describing their shoestring operating budget as “nothing,” or next to it. “It was a real miracle,” he says now. “Ken believed in me and we just tried to do the best we could.” Gradually, service jobs and repair work for Triad area clients started to trickle in, and Zion Guitars started to gain a reputation by word of mouth.

The business took a flying leap forward the following year when Hoover and Hampton befriended Seymour Duncan, one of the first custom guitar pickup makers. Duncan invited Zion Guitars to a National Association of Music Merchants show in Atlanta, so the duo packed up one of their early prototypes they called a Tele-Zion Powerglide, a tribute to the Telecaster, and Duncan let them display it in his booth. The NAMM is the big dog of trade shows, attracting artists and dealers from all over the globe. Hampton was strolling around the showroom floor taking in the sights when he bumped into Kansas founder/guitarist/songwriter Kerry Livgren. “He was just looking around and I said, ‘Hey, are you Kerry Livgren?’ He said ‘Yeah.’ I said, ‘You might want to come see what we’re up to,’ and he graciously came over to the booth, saw the guitar we made, and ordered one on the spot,” Hampton remembers. That national artist link was a turning point for the young company. “[It] just of sort of grew little by little,” Hampton says. “We just knew some people, and they knew some people.”

Another giant step for the company occurred when Guitar Player magazine commissioned a guitar to put on the cover. GP editor Tom Wheeler was aware of the work of another Greensboro artist, Wayne Jarrett, who has enjoyed a career custom-painting guitars for the likes of Prince, Alabama, and .38 Special, as well as motorcycles. Wheeler asked him if he could do a custom paint job on a guitar to be featured on the cover of the magazine. “And Wayne, bless his heart, he said, ‘Tom, why don’t you get these local guys here in Greensboro to build the guitar, and I’ll paint it,’ and that’s how it all started,” Hampton recalls.

Seymour Duncan provided the pickups, and bridge makers Floyd Rose had a new tunable locking tremolo that graced Zion-manufactured Silverbird for the cover.

But just when the business was going great guns, Hampton decided to take a leave of absence. He says his heart’s desire “had always been to build acoustic guitars. I was feeling that we got things going pretty good with Zion and Ken was really wanting to take it into the electric zone. I felt like it was time to move on.”

So in ’84, Hampton left — to go to Scotland for what he described as “a worship and mission ministry” to do whatever the church over there needed. “I was going over to be a servant,” he says humbly of his service for New Life Christian Fellowship in Hawick [pronounced “hoyk”], Scotland. “They had a youth group I was helping pastor, leading the worship.” He met his wife, Eileen during his stay from 1985–1990, and when he returned, resumed his friendship with Hoover, who passed away last year from complications due to MS. During their renewed time together, Hampton designed and built the Zion Primera guitar, which attracted the attention of Christian guitarist Phil Keaggy, who signed some early models. Hampton started his own business, Moriah guitars in 2008.

“I had been a builder from 1990 up till 2008,” he reveals during a tour of his shop. “Building houses, and what we would do here, I would acquire tools along the way, kind of like gathering moss along the way, and here are the machines that sort grew little by little.” Then by 2008–’09 he felt like he needed to get back into building guitars again. “And my children were bugging me, they were telling me ‘Daddy, why aren’t you doing that?’ So that’s what started this. We built the shop and I’ve probably moved four or five times in the last 10 years. We’ve been here about four years.”

In one of the back rooms of his cavernous headquarters, Hampton is showing off some of his exotic woods. He pulls out a slab of beautifully grained quilted maple that looks like designs have been etched into the wood, but it’s just the natural grain. Acquiring the materials is a treasure hunt for the luthier. “You’re always looking out for something really beautiful. Sometimes we’ll find a board somewhere, or somebody will find something,” he explains. Like his friend who went on a surf trip down to Costa Rica brought back a board of rain tree wood. “I’ve made a few guitars off that,” Hampton says. “And sometimes we buy wood off suppliers who do make the wood prepared for guitar-building.”

Ironically, you’ll see no completed instruments at Moriah. “We’ve got a few bodies, just got ’em to this stage,” Hampton says of the stack of raw forms on a shelf. “We don’t have a contract on anything, so we leave it at a certain spot and people can come in and put whatever they want on it.”

Most of his builds are custom orders, which is great for business, but leaves no showroom models.

“I’m thinking of building a bunch of them just to have for people to look at. A lot of times people come here, and all the guitars I’ve built are already gone,” he says.

And even though Hampton says he doesn’t have any nationally known people among his clientele, he is building instruments for local friends and people who have known him for years. The commissions keep him busy. He says he’s got about 16 acoustic guitars in process — none of them finished. “But we’re working really hard to get ’em done.”

And Hampton has capitulated to some electric projects. But only a bit. “There’s always been a designing thing going toward the electrics,” he concedes, “but I’ve always wanted it to go to the acoustic. That’s been my dream. That’s what we’ve finally been able to do . . . that’s what Moriah’s about.” OH

Grant Britt peruses his own collection of trashcan-rescued guitars displayed haphazardly against the walls of his tchotchke museum across form the graveyard.