Mudd in Yer Eye

Permaculture takes root in Greensboro

By Grant Britt

Once upon a time, public grazing was a no-no. Many of us older earthdwellers remember dire consequences for chowing down on public shrubbery and the fruits thereof. To do otherwise — picking berries, or digging up anything with roots and leaves in public parks would likely earn you a firm swat across your bottom. But lately, freethinking, food-for-the-masses agriculturalists have untightened the rules against free-range munchables, and public grazing is getting a second look.

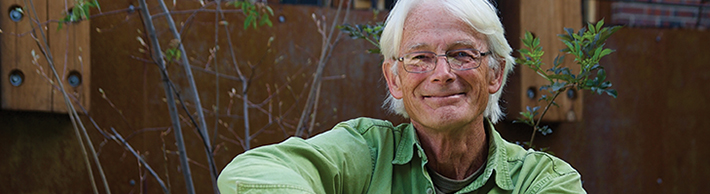

The rise of permaculutre is the culprit, creating edible landscapes. Former UNCG adjunct professor Charlie Headington is responsible for introducing Greensboro to permaculture 25 years ago after attending a lecture on the system. “I listened for about 15 minutes, realized this was something I wanted to do,” Headington says. He and his wife, Deborah, were avid gardeners, the kind who grow fruit in the front yard. “Permaculture gave us a bigger picture strategy, how to integrate fruit trees into it, capture your rainwater.”

“In permaculture, some spaces are left wild, others are restored, and still others are highly developed, as in an urban context,” Headington writes on the Greensboro Permaculture website, https://greensboropermacultureguild.wordpress.com/about/what-is-permaculture/. “Nutrient cycles, water storage, soil quality, and plant diversity are enhanced, while the resources flowing through the system are slowed down, stored, recycled and used sparingly,” he continues. “Small spaces can yield big harvests; human intervention, inputs, and maintenance are kept to a minimum. The aesthetic is pleasingly natural. Eighty percent of the work is in the initial installation, and 20 percent in its maintenance, the reverse of normal gardening, (devoting) less time to weeding and fighting insects and more to designing, harvesting, and learning.”

Headington was hooked: “I took a 72-hour course, learned more about it, from then on started doing workshops and introducing it to schools.”

It couldn’t have come at a better time for the professor, who was associated with the religious studies department and continual learning center at the university. “When you’re adjunct faculty, they should call them the agile faculty [since] you have to wear several hats. You have to be opportunistic,” Headington says.

“Permaculture became one of my hats that I wore, and it turned out to be a very happy endeavor,” he says. Although he continues to teach part-time on a graduate level online, he became the Gate City’s Johnny Appleseed of permaculture, introducing it to schools and churches. When the legendary chef and food activist Alice Waters came to town, he joined forces with her, touting the newly opened Edible Schoolyard at the Greensboro Children’s Museum.

“Permaculture gardens, farms and landscapes are organic, edible and diverse,” Headington writes on his website. “They are practical, low-maintenance and productive. Each element of the landscape, whether, plant, animal, or structural, is placed by the designer in a mutually beneficial relationship to its neighbor, the yields of one supporting the needs of the other. Permaculture designs and builds communities.”

It also attracts new converts who try to improve on the original model. Freelance writer David Mudd, who had just moved to Greensboro from a farm he was living on in Kentucky, took Headington’s course in 2013. Missing the rural life, Mudd wanted to connect with people with similar interests. He took the 72-hour course that is offered on weekends over a period of six months. “We’d go two days a week, amble around downtown, travel to farms in Summerfield,” Mudd recalls. They also visited abandoned lots that seemed as if they could be reclaimed and repurposed.

Mudd started the Greensboro Permaculture Guild because he says when he finished the course he wanted to just keep doing it. “I wanted to learn more, didn’t want to walk away from the people I had enjoyed hanging out with,” he says. “So I and a couple of others proposed us continuing to get together to teach and help one another, have lunch one day a week, and bring to one another what we wanted to do in our own yards, and what we might do to help other people interested in edible landscaping, urban gardening.”

Their first major project was at Elsewhere, Greensboro’s unconventional museum that collaborates with resident artists. Headington says he had been talking to co-founder and director George Sheer for a long time about reworking the weed-and junk-filled empty lot out back. When downtown developer and entrepreneur Andy Zimmerman started buying up adjacent property, Mudd enlisted his aid to work with him on landscaping the area. But Headington says the Guild tries to think beyond landscaping. “We’re not not only concerned with natural landscaping, but people landscaping,” he says. “You have to provide walkways and interesting venues along the way and plants play a part.” But there’s also a social aspect to it: “Urban design is really challenging,” Headington says, “because you have to think as much about people as you do about nature.”

The people/nature aspect has come together with an informal partnership with Habitat For Humanity.

We design edible landscapes for each house they bring online now,” Mudd says. “We make every effort to meet with the family/individuals targeted to own the house before the landscaping takes place” He says his team tries to “learn where they’re coming from, see what plants they know and make an edible landscape if that’s what they want.”

Habitat is a registered nonprofit, which enables the Guild to get nonprofit pricing from some area nurseries on trees and plants. “On the day of installation, one or two or three of us will be there to implement the plan we’ve come up with,” Mudd says. “But mostly it Habitat’s regular crew of volunteers who actually put the plants in the ground.”

In addition, there’s a Design Studio made up of people with good graphic and design skills. They work with homeowners and others on formulating landscape designs.

The Design Studio is made up of Guild members, some of whom have a degree in architecture, like lead designer Tay Hallas. “But we basically go by word of mouth, by what people like about what we do, and people seeking alternative designs themselves,” he says. “We certainly would love to add some landscape architects, but we’re kind of just growing now, we’re fledglings, so we’ll see what happens.”

Headington and the Guild are involved in a number of permaculture installations throughout town, working with Action Greensboro, an economic development group, and the Greensboro Parks and Recreation Department’s trail division on greenways and other projects. “I was just communicating with Parks and Rec the other day about refurbishing a park that had fallen on hard times,” Headington says. “They liked my ideas about bringing in native woodland plants that would also attract birds, butterflies, a variety of healthy insect life, so there’s just a growing interest in this.”

The Guild is particularly proud of their installation called the Meeting Place on the corner of Prescott and Smith. “It’s the first public orchard, was just a gas station at one point and now a popular little park on the triangular lot, with a gazebo,” Headington says. “We’re growing about 20 kinds of fruit there, have a big strawberry production, have peaches, pears.”

It’s more than something pretty to look at. “It’s part of that whole movement of people to not only be closer to nature, it’s not so much a romantic vision, it’s useful,” Headington says. “ It’s something we get food from, we gather rainwater, we lower our energy costs, and we have all this fresh food and, of course, kids love it, they’re very involved in it.” And best of all, the wee ones these days don’t get smacked when they dive in for grazing. OH

Grant Britt now grazes free rangily wherever nature catches his eye — without fear of retribution.