Five friends, a thousand paintings and the extraordinary legacy of Greensboro’s finest street artist

By Maria Johnson • Photographs by Lynn Donovan

It was a twist worthy of Maggie’s creativity.

There was a guy named Mike at the dog park. He had a basset hound, Buster. We got to be friends.

Mike and I did, too.

One day in 2014, as our pups snuffled around, Mike mentioned that he’d been helping an older lady who lived next door to him. She was having memory problems. She was an artist.

“What’s her name?” I said.

“Maggie Fickett,” he said.

My mouth dropped open. If I’d been running, I could have caught a Frisbee in my teeth as easily as any dog.

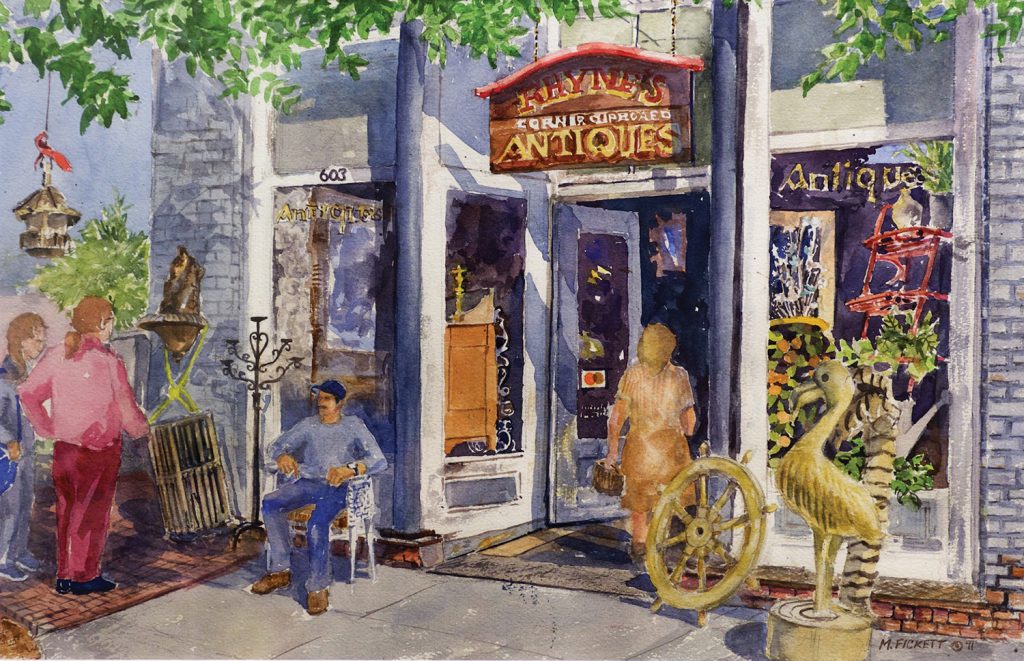

Thirty years before, as a newbie to Greensboro, I’d wandered into Maggie Fickett’s booth at a street fair. It was probably at Fun Fourth or CityStage, a now-defunct fall festival.

In any case, Maggie was minding a stall lined with her watercolors. As the daughter of an artist, I’d been taught to appreciate a keen eye and a quick hand. Here it was, right in front of me. A painting of Elm Street in downtown Greensboro caught my eye. It cost more than I wanted to part with, given my reporter’s salary. I exchanged greetings with the ash-blonde lady in the booth and left without the painting.

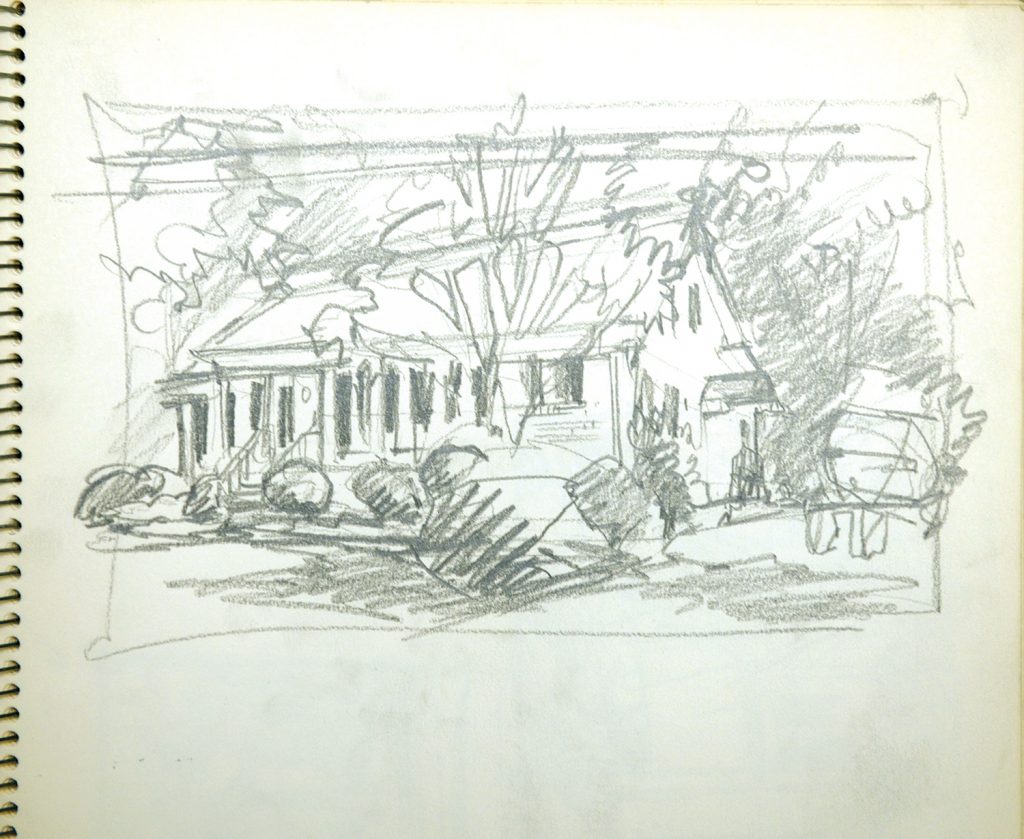

I regretted not buying that piece for a long time, but it did not diminish my fondness for Maggie’s work. I kept up with her loosely, through word of mouth and sightings around town. She was known for working en plein air, or on location. It wasn’t unusual to see her perched on a folding stool, sketching in a park or at a construction site.

She was a favorite subject of photographers at the News & Record where I worked. They often turned in Maggie’s picture as a stand-alone feature photo. It usually fell to a reporter who worked nights to write a cutline about the photo while weaving in, not very subtly, the next day’s weather forecast.

“Fickett spent Wednesday afternoon in Lake Daniel Park in Greensboro painting,” said a cutline that accompanied Maggie’s picture in January 1986. “‘When the weather gets good, I’ve got to get out and do something,’ she said. But the mild weather will end today with a high only in the low 40s . . .”

I saw Maggie’s work around town, in galleries and offices. Her prices climbed, and so did my appreciation for what she was doing. I came to regard her as the finest artistic chronicler of daily life in Greensboro in the waning years of the last century.

It wasn’t just how she painted, with a looseness that signaled deep study, but what she painted, which was basically everything she saw.

She preserved the unvarnished truth. Her streetscapes contained landmark buildings, yes, but also fire hydrants, and telephone lines, and birds, and traffic signals and campaign signs. There, on display, were all kinds of people, fashion, cars, seasons and animals.

Where other artists might edit out the “junk,” Maggie understood that recording the details was essential to recording the era. She froze time, but her work wasn’t frozen. It was fluid, full of life.

And yet, in the midst of the hubbub, her paintings were balanced, harmonious.

I might have been the biggest Maggie Fickett fan who didn’t own a Maggie Fickett painting.

Mike’s aside at the dog park brought all of that back to me.

I was happy that Maggie had a neighbor as trustworthy as Mike. Others had taken advantage of her kindness and her checkbook. Mike looked out for her. He communicated with Maggie’s nephew and wife in Maine.

Several months later, in April 2015, Mike broke the news.

Maggie, who’d never married or had children, had left Greensboro. Her nephew, Bob, and his wife, Debbie, had moved her back to Maine, where Maggie had been born 84 years before. Bob and Debbie were coming to Greensboro to finish cleaning out Maggie’s house before selling it.

Would I like to meet them?

Absolutely.

It was pouring rain when I rolled to a stop in front of Maggie’s brick bungalow on Mayflower Drive near UNCG.

Mike was there. So were Debbie and Bob. So was Lynn Donovan, an O.Henry photographer with a deep knowledge of the Greensboro arts scene. The house was musty and smelled of cats, Maggie’s companions for years.

It was a tired house, a dated house, in the way that the homes of the elderly often become. Also, the place was being dismantled, so it was half-dressed, a state that always embarrasses me a little, as if I’ve walked in on someone stepping out of the shower.

Bob and Debbie had already taken the art they wanted to keep. They would stash the rest in a storage unit while they figured out what to do with it.

“The rest” amounted to more than 1,000 pieces. They were scattered about, stacked on shelves, on tables, in closets. Some of the work was framed. Most of it was unframed.

Hundreds of unsold prints were sealed in plastic. They depicted iconic Greensboro places: the F.W. Woolworth store downtown, home of the 1960 sit-ins; Yum Yum Better Ice Cream and Hot Dogs; War Memorial Stadium; Ham’s restaurant on Friendly Avenue; the Boar and Castle drive-in; West Market Street United Methodist Church.

We thumbed through Maggie’s original work, hundreds more pieces. Like the pulpy paper they were painted on, her renderings were rich to the touch and to the eye.

Flipping through her work was like taking a tour of Greensboro, with recognizable homes, streets, parks and gardens. Her still-life paintings juxtaposed flowers, vegetables, bottles, and knick-knacks, some still visible in in the house.

There, too, were paintings of places we did not recognize — beaches, city skylines, mountain valley farms, woody hillsides. And cats. Lots and lots of cats.

One of the cat paintings, an unframed watercolor on paper, stopped me. It showed two felines, both black and white, lounging in the folds of a red throw. The little leos were curled, facing each other. The background was impressionistic. The cats were sharper.

The thing that arrested me was a flap of onionskin paper. Maggie had used masking tape to attach a scrap of onionskin to the edge of the sketch paper. On the underside of the onionskin, she’d rubbed a graphite patch with the broad side of a pencil. On the top of the onionskin, she’d traced the contours of one cat’s face, applying pressure to literally make a carbon copy. She hadn’t been happy with the cat’s original face, and she wasn’t going to quit until it fit her vision of what it should be — or at least got closer.

That told me everything I needed to know about Maggie as an artist.

“That’s Jimmy and Emmett,” Debbie said, identifying the father and son that Maggie once owned. When she moved, she was down to one cat, Shadow. Mike was taking care of Shadow.

I made my case to Debbie quickly. I wanted to do a story about Maggie and her art and what it meant to Greensboro. But where to start?

I couldn’t interview Maggie, and it would be hard to grasp the scope of her work without sorting through the brimming gallery of paintings she left behind.

Later, Debbie and I made a few calls to local organizations. No one wanted the job of cataloging Maggie’s work.

So a few of us made a pact. We would go through Maggie’s work in storage, describe and record what we deemed the sellable pieces, then turn the ledger over to Maggie’s family, hoping that — when they found someone to dispose of it — Maggie would get her due, artistically and financially.

We were quite a team, Fickett’s Charge. We consisted of her devoted neighbor, Mike Decker; photographer Lynn Donovan and her husband Dan; my dear friend and former colleague Jim Schlosser, who’s a walking encyclopedia of Greensboro history; and yours truly.

We met a dozen times at the storage unit, working for a couple of hours every time, usually on a weekday afternoon.

We learned a lot in those visits, chiefly that we all enjoyed each other and Maggie, too. She made us laugh. She had a delicious sense of humor. Sometimes, she jotted witty comments beside her preliminary drawings.

Her satirical posters were a hoot. One depicts the evolution of women’s fashion as a circle, starting with a cave woman wearing a leopard skin, progressing through women in corsets and pencil skirts and business suits, cycling all the way back to a modern woman in a leopard dress and platform sandals.

The two leopard-clad women stand face-to-face, regarding each other with looks that say, “Don’t I know you?”

Sometimes, we laughed at things that Maggie didn’t intend to be funny, but that probably would have tickled her, too.

One example was a series of the same scene — the taillights of a car on a highway. It was painted from the viewpoint of a trailing car.

Maggie tackled that scene over and over and over again. In different lights. In different colors. In different styles. In different levels of detail.

Delirious from the repetition and numb from the meat-locker temperatures, we cracked up with laughter on the day we came across those paintings.

“Really, Maggie?” we teased aloud. “Who the hell was in that car ahead

of you?!”

Piece by piece, we grew to love Maggie’s spirit, her sensitivity, her work ethic.

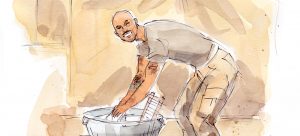

She painted or drew every day. She once told her dear friend and fellow Greensboro artist Jane Averill that she thought she might have Attention Deficit Disorder. She couldn’t focus, she told Jane, unless she was drawing or painting. Art delivered Maggie, and she gave in to her muse, which made beautiful things happen between her eye and hand.

Our respect for Maggie filled in, like glue, between the biographical bits of her life we already knew — and those we would come to find out.

A child of the Great Depression, Margaret Ellen Fickett was born in South Portland, Maine, in 1930. Her parents were farmers. They directed most of their attention to their son, Robert II, Maggie’s younger brother and only sibling. Maggie’s early life was difficult.

“It was just a very, very harsh, cold family,” says Debbie Fickett, who’s married to Maggie’s nephew Bob.

Maggie knew at a young age that she was an artist, but her family had little use for art. After graduating from high school, she worked in a Catholic hospital, prepping slides for a pathologist. The nuns at the hospital found out about her artistic ability. They encouraged her to attend fine arts school.

Maggie’s father refused to pay for a fine arts education, but he agreed to pay for commercial art school so Maggie could get a job. He took her to Boston and left her in a basement apartment. She had one year to make it, he said.

Maggie was on her own. She might have been emotionally starved, but she had been dropped in a visual Valhalla, and she feasted her eyes on Boston.

The macro and the micro enthralled her. She sketched and painted architectural details – cornices, iron railings, bay windows, columns, steps – as well as wide-angle views of Boston Harbor, Boston Common, Boston Public Garden, Beacon Hill and the Charles River.

She finished the School of Practical Art and worked as a commercial artist in Boston, but she didn’t enjoy it. She sought refuge in her days off, wandering the streets with pad, pencil and paint. She honed her skills by taking more classes at the Museum of Fine Arts and the Massachusetts College of Art.

She played with different styles. At times, her work appeared cartoonish. At others, abstract or impressionistic.

She experimented with acrylics and oils before settling into the medium that would define her work: watercolor.

“I enjoy working in WC because its light weight and fast application are very well suited to my temperament,” she wrote years later.

She painted scenes for a greeting card company. She worked at a Boston ad agency for 15 years. Her sketchbooks, dotted with self-portraits and snippets of herself, such as a curled hand holding a cigarette, suggest that she lived alone during most this time, but she was not without company. Lithe and blonde, with crackling blue eyes, Maggie dated several men, including a fellow from her hometown.

They were engaged for a while, but he was too quiet, she told friends. When she asked him why he spoke so little, he told her it was because she had a mind like a steel trap; she remembered everything he said.

His answer did not inspire confidence. Maggie gave back the ring.

Other developments pushed her out of Beantown.

“After being evicted several times to make way for condominiums in Boston’s Back Bay, I quit the job and came South at the suggestion of a friend here,” she wrote in one of her sketchbooks.

Driving a car packed with a sedated cat and her belongings, Maggie landed in Greensboro in May 1979.

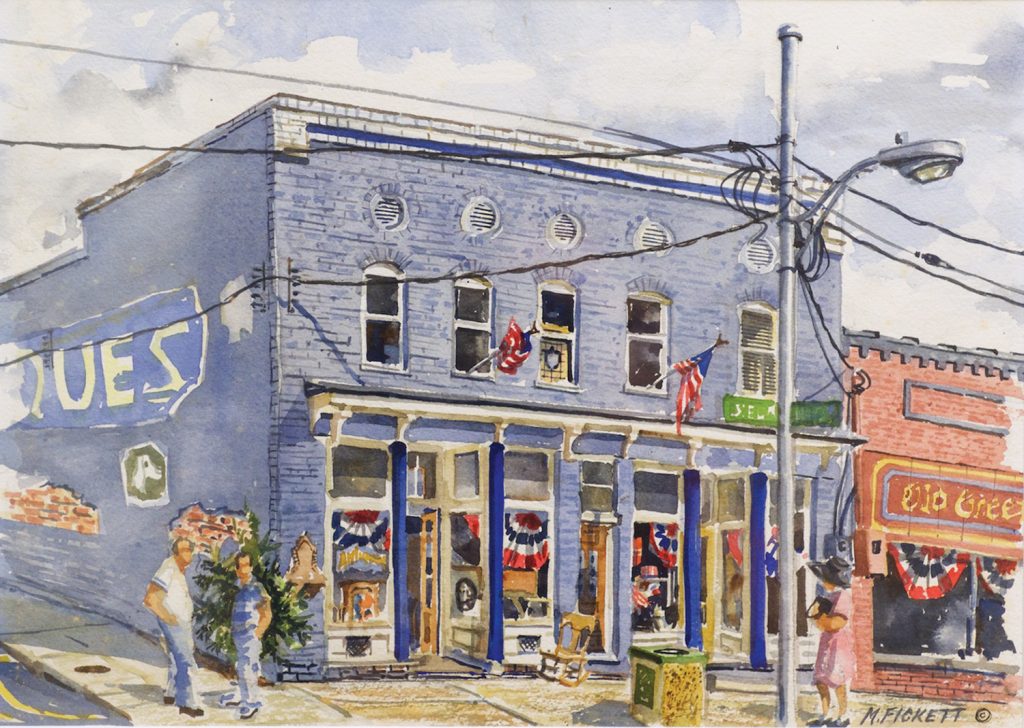

“Didn’t know what I would do, but knew it wouldn’t be commercial art,” Maggie wrote. “Once I discovered Old Greensboro, I got the urge to do street scenes again . . .While working there, I was approached by a merchant who asked if I would do a watercolor of his home. This opened a whole new field for me . . .”

Thanks to Bob Blumenthal, who owned Blumenthal’s clothing store, Maggie had found her bread and butter: preserving private dwellings on paper.

Her patrons became her friends and champions, touting her work to others, who hired her to paint their own homes.

Maggie briefly considered leaving Greensboro. About a year after she arrived, her former employer, the Boston ad agency, wanted her back. She was tempted, but Greensboro had a lot to offer. She felt safe here – she’d been mugged twice in Boston – and people recognized her on the streets. They called her by name. It meant a lot to someone who was plagued by self-doubt.

She stayed and painted a new life for herself.

Her career rested on house portraits in Greensboro’s toniest neighborhoods: Old Irving Park, Starmount and Sunset Hills. She worked in Jamestown and High Point. Often her clients had second homes, and they hired Maggie to paint those, too.

Known for refusing to edit the gritty details out her street scenes, Maggie obliged her house-proud patrons.

“I can take out telephone poles and wire,” she told an interviewer. “I can change the seasons, put blossoms on the trees.”

She recorded landmark public buildings, too.

Occasionally, she painted a building that had been demolished, using pictures as her guide, but she wasn’t terribly interested in painting long-gone structures. The buildings she painted would be historical soon enough, by dint of development or disaster, she believed.

In 1981, fire confirmed her approach, gutting the Carolina Theatre on South Greene Street. The shell of the building survived. The interior was overhauled. Maggie made a print of the theater to coincide with its reopening the following year.

She captured South Davie Street in 1984, a year before a fire ravaged the area. She painted the George C. Brown & Co. plant, a cedar mill, before the complex ignited in 1997. She stuck to the present day while it lasted.

“I prefer to work on location and endeavor to catch the fleeting moment,” she wrote in a sketchbook. “Very often an unsuspecting pedestrian wanders into my scene and . . .”

Maggie immortalized the bystander. Typically, she sketched on location and trundled her pieces home, to a rental house on Spring Garden Street, to finish them.

“Although my scenes take two or three days to complete, I try to convey the feeling of spontaneity,” she wrote.

Often, she sold two versions of her landmark scenes: black-and-white prints of her pen-and-ink drawings; and hand-colored versions. She charged $10 for the plain prints, and $30 to $50 more for hand coloring, depending on the complexity of the subject.

She sold her work through the Greensboro Artists’ League, galleries, in-home shows and exhibits in office hallways.

Jim and Diane Stanley decorated the walls of their accounting firm with what they called a “Greensboro Collection,” local scenes by several artists: Wendy Wallace, Bill Mangum, Dale Gallon, Larry Johnson, Craig Hyman, Maggi Clark, Allan Nance and others.

Fickett’s work, more than 40 pieces in all, formed the foundation of the Stanleys’ 100-piece collection.

“Her style was so easy,” says Diane Stanley.

And portable.

Maggie left Greensboro in 1986, moving to coastal Wilmington, possibly to follow a man. She drew a light-hearted postcard to announce the move. The card shows Maggie in sunglasses, on the beach, surrounded by four cats. A paintbrush is tucked behind her right ear.

“WE’RE MOVING!,” the postcard says. “Our new home will be 501 S. Front Street effective 6-30-86.”

Two years later, she came back to Greensboro alone. Debbie Fickett guesses that there could have been another broken engagement. Maggie, a model of New England reserve, divulged little to family and friends.

She soothed herself with art.

“It was her escape,” says her friend, Jane Averill.

Old Greensborough, the historic area around South Elm Street between McGee Street and Gate City Boulevard, was Maggie’s favorite stomping ground. Southern Living magazine wrote about the district in March 1992. Maggie was the lead.

“I like to work on Sundays when there isn’t much traffic,” she told the writer. “Just me and the street.”

The changing face of downtown fascinated her. Wherever cranes swung wrecking balls and hoisted girders, Maggie was sure to be nearby.

She captured the construction of a second tower at Jefferson-Pilot headquarters, now a part of Lincoln Financial Group. She caught, in progress, an addition to the Greensboro History Museum. She recorded the birth of the downtown Marriott hotel.

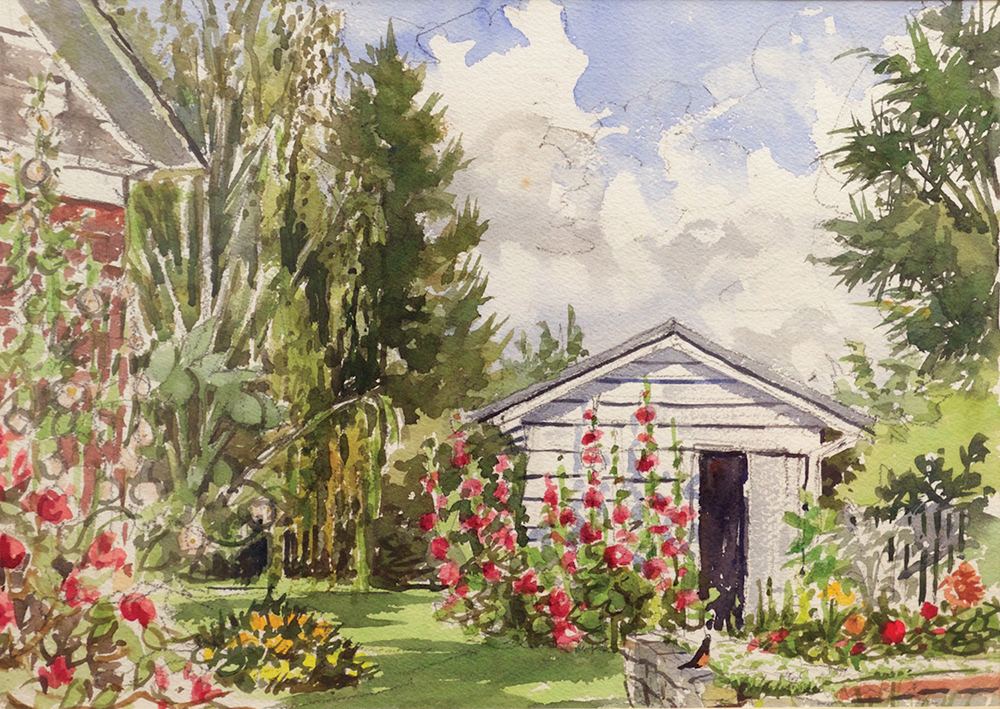

She resumed painting homes, including her own. After returning from Wilmington, she bought the bungalow on Mayflower Drive. She found inspiration in every corner.

Outside, she painted her garden, her home, her neighbors’ homes.

Inside, she painted her cats, her kitchen, the views from her windows and doors. A night owl, Maggie worked into the wee hours. The snowy screen of her rabbit-eared television kept her company.

Before screen shots were a thing, she captured Aretha Franklin. And Diahann Carroll. And people in courtroom reality shows. “Hootchie Mama (judge’s words)” Maggie wrote under the rendering of a provocatively dressed woman.

Everything was fair game to Maggie. What others might express in writing or by telling a story verbally, Maggie communicated in art. She talked in pen, pencil and watercolor.

When she traveled to Bermuda, she spoke of sun-bleached walls and impossibly blue water. Virginia was patchwork farms laid across valleys like quilts; Seagrove was kilns tucked under sloped sheds. In Maggie’s vernacular, Burlington was the carousel; Graham, the movie theater on Main Street; Winston-Salem, R.J. Reynolds Tobacco Buildings. And Pinehurst? Not the golf courses that typically come to mind but horses that circled the harness track.

Her friend and patron, Greensboro developer George Carr, drove her to Pinehurst to capture the trotters.

“I liked the way Maggie could create a good image without it being too architecturally perfect,” Carr says. “I never wanted to use another artist after her. She would capture the relevant things that you didn’t know where relevant until you saw her art.”

Maggie pushed herself to improve, even when most people considered her accomplished. In preparation for a watercolor class, she filled out a survey assessing her skills. She rated herself strong in realism and description. She wanted her work to be simpler, looser, more painterly.

The survey ended by asking the students what their goals were. Among the many choices were “sell paintings,” “win an award,” and “produce paintings I find satisfying.”

Maggie checked only the last one.

No one who knew her would have been surprised.

If Maggie had enough money to live on, she considered herself a success. Her art came first. The rest of her life molded around that. She lived simply.

On Sundays, she attended mass at downtown’s St. Benedict Catholic Church.

She ate tuna fish, noodle casseroles and vegetables from her garden.

She splurged on tickets for the symphony, where she sometimes sketched right over the program notes, and on clothes from consignment shops. She gravitated to denim skirts, Bohemian tops and purses that did not match her shoes.

“She wanted funky clothes, nice funky clothes,” says her friend Jane Averill. Maggie’s free style was an extension of her values. Her inclination was to nurture and let be. She fussed at her neighbor, Mike, when he mowed over flowering weeds in her yard. She paid for ballet lessons for Debbie and Bob’s daughter. She donated to her church, to firefighters, to St. Jude Children’s Hospital, to the Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Animals.

Toward the end of her years in Greensboro, she became an easy mark for scammers.

She knew she was slipping.

She left a note for a friend who stayed with her.

“I want to apologize for not being fully ready for your arrival tonight. As you and everyone knows by now, my memory has gone down the road and around the corner. Much to my dismay,” she wrote.

Her fender benders mounted. She missed appointments. She lost weight because she forgot to eat. Then came the calls from police saying that Maggie had been found acting confused at a grocery store or gas station.

Maggie had always been a little scatterbrained, like many artists, but finally it dawned on her relatives and friends that she had dementia.

She was diagnosed with Alzheimer’s disease. A doctor said that Maggie should not be driving. Maggie was angry. She told her friends to mind their own business. She was determined to drive. Her friends hid the keys and took the distributor cap from her car’s engine. Maggie started walking. She drifted for miles, unable to find her way home. She wouldn’t stay in the house.

It was time.

Mike, her neighbor, and Jane, her friend, cried as Debbie drove away with Maggie that June.

By the time they got to Maine, Maggie had forgotten what Greensboro was.

She sketched the whole way.

She seems happy today, in the assisted living center that cares for people with memory loss. Whenever Debbie appears, Maggie stares at her.

“Maggie! It’s wonderful to see you!” Debbie will say.

Maggie, now 87, always breaks into a smile.

She enjoys gardening on the grounds, puttering in special planters that stand waist-high. She dresses up for parties. From time to time, a night nurse on the Wyeth wing — named for one of Maggie’s favorite artists, Andrew Wyeth — helps her to draw while the other residents sleep.

As darkness deepens, a light shines in Maggie’s room. OH

Maria Johnson is a contributing editor of O.Henry magazine. She can be reached at ohenrymaria@gmail.com.

Art for Art’s Sake

When it comes to the art that’s cached in Greensboro, Maggie’s family would like for a college or nonprofit group to show and sell the works, with most of the proceeds going to create an art scholarship in Maggie’s name.

They’d also like to see some of Maggie’s paintings and sketchbooks archived here.

“We want her life’s work to create more art,” says Debbie. “That was so important to her, that the world be filled with art.” Debbie Fickett can be reached at sebago14@gmail.com. —M.J.