O.Henry Ending

The Naked Truth

How I really feel about birthday suits

By David Claude Bailey

“Dad! Put your shirt on,” my daughter scolds as we leave the beach at Zahara de los Atunes, a shoreside village on the Atlantic west of Gibraltar.

“What?” I shoot back. “We just left a beach where a third of the women were topless, and you want me to put my shirt on?”

Sarah explains that no one in Spain with any couth goes shirtless on the streets in beach resorts — or anywhere else in public, except bathing venues.

Here in the states, I can jog down the street shirtless without anyone blinking an eye (though they might look the other way, given my physique). Only in nudist colonies (like the one outside of Reidsville you read about last month in O.Henry) do women and men go around in their birthday suits. But, oh, those sexy Europeans.

Each time my wife, Anne, and I come back from visiting our daughter in Spain, my hiking buddies are envious of my basking in the Mediterranean sun surrounded by bare-breasted beauties. “Did you take any pictures?” they ask.

Back in the spring, only a few days after Spain lifted their COVID ban on American tourists, I dipped my toes in the water at a nude beach. Anne, Alice and I were visiting Sarah on the Spanish island of Mallorca. We had driven to a remote beach near S’Albufera, a vast marshland preserve on the east coast. When I set off for one of my notoriously long walks, Sarah said, “Dad, you’ll probably see a lot of nudists. Try not to stare.” In fact, Sarah knew I had stopped fixing my gaze on nude sunbathers several years ago, not because I was tired of seeing stunningly trim and attractive examples of the human anatomy, but because of something she’d told me: “Maybe you’ve noticed that a lot of kids under the age of three don’t wear swimming suits over here. Nudity and toplessness are ways for adults to recapture those carefree, early experiences of being unencumbered with clothes, of feeling the sun and saltwater all over them.”

Walking down the undeveloped stretch of sugar-white sand, I saw moms, dads and kids building sandcastles without the advantage of any clothes. Elderly couples sunned together in the altogether. Single men and women walked and talked and swam unclad without appearing to me in the least bit sexy. In fact, the women wearing string bikinis seemed to be making a much more tantalizing fashion statement.

A final au naturel, European-style, story.

Some years ago, when nudism and the topless thing were brand new to Anne and myself, Sarah took us on a long hike. We were on the coast near Llucalcari (pronounced in Catalan “You Call Car-ee”), a village named for its once sacred woodland grove. A friend had told Sarah about an enchanting beach accessible only by a primitive, handmade ladder of grapevines and driftwood. “It’s a favorite haunt for nudists,” Sarah told us. At the end of several hours of hiking, I eagerly scrambled down the vines and headed down a narrow path toward Homer’s wine-dark sea, only to encounter three nude 20-something women. They were headed back up the path to a spring where water poured from the hillside. We passed within inches of one another and I couldn’t help but notice their outstanding anatomical features — covered in dark purple mud that they’d smeared on themselves from the hillside as a self-administered spa treatment. I stood to the side to let them pass and smiled. They smiled back, a sticky, purple vision from head-to-foot, with only the whites of their eyes and teeth shining comically. As they passed, we all broke out in giggles.

“Given my experience in Spain,” I tell my hiking friends, “nudism in Europe is not all it’s cracked up to be.’” OH

David Claude Bailey is a contributing editor of O.Henry. Although he doesn’t offer details, he claims the purple mud does, in fact, work wonders.

Almanac November ’21

November Almanac

By Ashley Wahl

November is the rush of wind through leaves, the rush of leaves through wind, a cradle song before a long night’s sleep.

In the garden, the unblinking statue has seen it all before, will see it all again: birds, here and gone; the explosion of color; the great release; the withering; the nothingness; the sweet and glorious rebirth.

Today, light feels soft and precious. The air is cool. The garden statue, barnacled from yet another sleepless year on watch, holds a stone bird in cupped hands — the weight of the world; the burden and the gift of the silent witness.

As tree limbs bend and sway on high, leaves and squirrels scatter across the earth in dramatic bursts.

Soon, when the wood frogs sleep, the roving cat will make its way from the rose bed to the back porch, press its paw against the glass panel door, give up its wanderings for a place by the hearth. The crickets play their final tune as the snake enters brumation.

In its quiet meditation, the statue sees and hears what most do not. It knows that summer’s light is still here, pulsing within all living things; that spring is autumn’s waking dream; that there is magic in the heart of winter’s stillness.

A whirl of golden leaves descends. An aster blooms. And in the fading autumn light, a pregnant doe plucks freshly planted bulbs, nibbles dwindling grasses, steps boldly toward the night.

The statue neither smiles nor frowns. It simply watches, listens as the world goes quiet.

Pass the Gravy

Autumn’s color show does not stop at the swirling leaves. Inside, where golden milk simmers on the stovetop, the spectacle continues.

Behold a rainbow spread of roasted beets and carrots. Collard greens flaked with red pepper. Cranberry-pear chutney garnished with orange peel.

Come Thanksgiving, add warmth and color any way you can. We all know it: The mashed potatoes need the contrast.

Despite how you serve them — smooth and creamy; hand-mashed and skin-on; loaded with garlic and butter — there’s no denying that mashed potatoes remain a holiday favorite.

Unlike green bean casserole, which Campbell’s introduced in the 1950s through their Cream of Mushroom soup, mashed potatoes have been a Thanksgiving staple since the 1700s.

Sure, add a dollop of sour cream and a little cheddar. Or fresh rosemary from the kitchen garden. Just don’t go messing up a good thing.

Hold the Dairy

How to make vegan mashed potatoes? Two words: vegan butter. And as for vegan gravy? Ditto. Sub pan drippings for nutritional yeast, soy sauce, Dijon mustard, onion powder and the like. There are dozens of recipes out there. No need for the vegan you love to go without.

I love to see the cottage smoke

Curl upwards through the trees,

The pigeons nestled round the cote

On November days like these . . .

— John Clare, “Autumn”

Southside Reimagined

Transforming Greensboro one office — and vision — at a time

By Maria Johnson

Photographs by Amy Freeman

Thirty-three-year-old Dan Brown, founder of one of Greensboro’s newest start-ups, Precise 3D Scans, has just moved into a new office, and he has lots of ideas about how to make it his own.

Slide a bookcase against one wall.

Hang a couple of motivational posters.

Prop some photos of his wife and 3-year-old son on his laminate desk, which came with the space, along with an ergonomically correct chair.

There isn’t room for much more. The space is roughly 6-by-7 feet and industrially chic with bright white walls, concrete floors and fluorescent lights overhead. But at this stage, Brown, who started his one-man business in the spring of 2020 — yes, that spring — doesn’t need much more, aesthetically speaking.

What he does require is an affordable place to work outside of his home, a place where he can drill down, for about 10 hours a day, in his specialty: making 3D virtual tours of apartments, stores, schools and the like. At the moment, his MacBook Air is propped open, next to a couple of crinkly plastic water bottles and his earbud box. He’s fine-tuning an interior view of the Nike House of Innovation in Paris.

Yes, that Nike. And that Paris.

Whenever he wants, he can open the glass door of his office — the wall facing the hallway is entirely glass — to mill around with other entrepreneurs, swapping small talk, pinging ideas and harvesting support as he goes.

His neighbors include writers, real estate agents, architects, techies and Mayor Nancy Vaughan, who’s using the space for her re-election campaign.

Tenants — they’re called “members” here — share conference rooms, printers, business supplies, a reception desk and an airy common area with modern furnishings, low-light plants and a long wooden bar with ready-made coffee, an espresso machine and beer on tap.

“I’m a really social person,” Brown says, his eyes smiling over his paper mask. “But for the most part, when I’m here, I’m really siloed in. This building has been wonderful.”

A place to burrow in — as well as a place to socialize and experience “happy collisions” with people in different fields — is just what Andy Zimmerman and his business partner Ken Causey had in mind when they soft-opened a second location of Transform GSO, a co-working office space, in the trendy Southside district of downtown Greensboro in September.

Last month, they celebrated the 22,000-square-foot expansion — inside the old Blue Bell textile mill at the corner of South Elm and Bain streets — with an official opening and more explanations of the co-working model.

“It’s kind of like a coffee shop where the coffee is free, but you pay to be here,” says Causey, Transform’s techie-in-chief.

Zimmerman continues: “A lot of co-working spaces are real estate businesses. Not that we’re not, but first and foremost, we’re a community. That’s our total drive. We wanted to create our own community of entrepreneurs.”

The latest Transform site, sporting a new entrance at 111 Bain Street, joins a smaller sister location, the former HQ Greensboro, which opened at 111 Lewis Street, one block away, in 2014.

Already, Transform on Bain has leased two-thirds of the 52 work spaces, with rents stretching from $1,550 a month for the largest rooms, suitable for five or six people, to $20 for a day pass that covers access to the common area and bottomless coffee.

Potential members can choose from nine packages, each with different perks. Leases run for 12 months versus the five-year terms that are standard for many commercial properties, and all Transform members can use the shared spaces at both sites, including a lushly landscaped area and vegetable garden maintained by the Greensboro Permaculture Guild.

“Members can come and pick a tomato. Honestly, anyone can come and pick a tomato,” Zimmerman says.

O.Henry magazine recently moved its office to Transform on Bain.

Zimmerman explains the draw for many small businesses.

“The only rhyme or reason is the cool spaces, the flexibility and the collaboration,” he says. “I’m not sure there’s another place in Greensboro that has these components in a critical mass.”

Zimmerman says it’s his favorite story: how he came to buy the 100,000-square-foot Gateway Building, an L-shaped colossus that housed the Blue Bell Co. offices and textile plant at 620 South Elm Street through most of the 20th century.

In the early 1900s, the plant wove denim and sewed it into overalls that were popular with railroaders on the nearby Southern Railway. Production shifted to military uniforms during World War II. Most of the factory workers were women.

Civic powerhouse Betty Cone owned the building — then called the Old Greensborough Gateway Center — by the time it caught Zimmerman’s interest.

He called her in 2016.

“I know it’s not for sale, but if it ever is, I’d be interested,” said Zimmerman.

“You’re right — it’s not,” said Cone, “But I know about your work.”

Six months later, Cone called Zimmerman.

“Are you still interested?” she said.

“Yes,” said Zimmerman. “When can you meet?”

“How about now?” offered Cone.

A couple of hours later, the transaction was sealed, face-to-face, with a verbal agreement.

“We made a deal the old-fashioned way,” says Zimmerman. “We dotted the ‘i’s’ and crossed the ‘t’s’ later.”

Zimmerman added the property, which Cone had sectioned into offices and studios, to a half-dozen other parcels he owned in Southside, but there was one hitch: He wasn’t sure what to do with his new acquisition.

“Ready, fire, aim — that used to be my way,” Zimmerman says, poking gentle fun at himself.

Gradually, he and Causey decided to expand the co-working venture that was operating on Lewis street. With the help of general contractor R.P. Murray, they ripped out drywall and low ceilings, uncovered 55-pane factory windows that had been blocked by bricks or concrete blocks, and installed new electrical, HVAC, plumbing and motion-sensitive lighting systems.

They also brought in gigabit fiber optic cable, assuring the ability to live stream and download large video and audio files.

The first stage of the makeover, inside the brick wing that faces South Elm Street, opened in 2019. Centric Brands, a New York-based designer of clothing and accessories, moved in.

The rest of the Gateway Building — including the stucco-clad leg that houses the common area of Transform and all of a wedding and corporate event space called Elm & Bain — was delayed by COVID and finally brought online in September.

“This is a community we’re creating here — work here, play here and hopefully live here,” says Zimmerman, who fondly recalls Green’s Supper Club on U.S. 29 north of Greensboro and wants to make Elm & Bain the home of a monthly Southside Supper Club with live entertainment and catered multicourse meals.

“I personally have graduated from standing shoulder-to-shoulder to listen to live music,” he says.

Zimmerman also plans to develop 240 apartment units across Gate City Boulevard with parking to support both the apartments and the Gateway/Transform complex.

The busy intersection is already home to Union Square Campus, a health sciences education building operated jointly by Cone Health, UNCG, N.C. A&T and GTCC.

“We’re breaking down the silos that have existed here in Greensboro for a long time, hopefully with The Gateway and Transform Greensboro being at the heart,” Zimmerman says.

No one would wish a pandemic on anyone, but COVID-19 hasn’t hurt his team’s dream.

“The demand for remote employment has gone up so much,” says Transform GSO’s executive director Kaitlin Conover. “We’re having a lot of people coming in because they’ve been working from home. This gives them a break, a respite.”

That’s the case for Dan Brown, the 3D entrepreneur.

He started his business last year, soon after he and his wife, Madeline, moved from New Jersey to Greensboro for her job in the office of student retention at N.C. A&T. When COVID hit, both of them were working from home, occasionally with Madeline’s mother trying to babysit their son in the background.

“If he knew I was there, it was ‘Daddy, daddy, daddy, can I get some fruit snacks?’ and when I didn’t respond, it was, ‘DADDY, CAN I GET SOME FRUIT SNACKS?!!’ I said to myself, ‘This can’t work.’”

In June 2020, Brown started camping out at the Greene Street office of Collab, a hatchery for entrepreneurs fostered by Launch Greensboro, an arm of the Greensboro Chamber of Commerce.

“It was one of the best moves I’ve ever made, especially for the networking and connecting,” he says.

When Launch Greensboro moved into the new location of Transform GSO, a dozen Collab inhabitants, including Brown, followed.

“The whole ecosystem — it’s been a continuation of the excellence I’ve experienced from day one,” says Brown. “I’m grateful to have a space to work out of. I like to get out of the house and go somewhere. I’m an extremely routine-oriented guy.”

To that end, he’s adding one more item to his list of office decorations: frosted peel-and-stick window film to cover the glass door of his stall and make the space more private.

“I know myself,” he says. “I need to put the blinders on and zone out.” OH

Maria Johnson is a contributing editor of O.Henry. Email her at ohenrymaria@gmail.com.

Ten To One

A Visionary Perspective

A lot can happen in 10 years. This city — and magazine — are living proof. Greensboro’s past and present have graced our pages over the last decade. Heading into our next 10 years, we decided to ask a handful of Gate City visionaries 10 questions, including their hopes and dreams for what Greensboro might look like 10 years from now. We’ll let them do the talking.

HAROLD L. MARTIN SR.

Harold L. Martin Sr. has served as chancellor of North Carolina A&T State University since 2009 and is the first alumnus ever to hold the position. Martin was heralded as an education and business thought leader in TIME magazine’s 2020 edition of The Leadership Brief. In 2019, he was honored by the Thurgood Marshall College Fund with the Education Leadership Award, and in 2017 he was named America’s most influential Historically Black Colleges and Universities leader by HBCU Digest. In 2015, Martin was named to the EBONY Power 100 list alongside some of the nation’s most prominent African American thinkers, artists, government officials and business leaders. Under his leadership, A&T has emerged as the top-ranked historically black public university in the nation.

OH: What was it like growing up in Winston-Salem?

HM: Often I refer to the saying, “It takes a village to raise a child.” I lived in that village — it was both protective and supportive. Our school, Carver Consolidated School, was segregated. I began Carver in first grade and ultimately graduated in the last senior class before the school became integrated. Carver was a critical part of our community.

OH: What role did your parents play in determining your path in life?

HM: Our parents were not able to get a college education themselves. They grew up in large families — each came from a family of 13 children — and they were poor. My father was a Baptist minister, so there were high expectations for the behavior of my brother, sister and I. Our parents were highly committed to the three of us going to college — no exceptions.

OH: Why did you decide to attend North Carolina A&T State University?

HM: One of my most influential teachers — my high school basketball and tennis coach — had graduated from A&T and my brother and sister already were students. But I had a basketball scholarship to attend Ohio Wesleyan University. During my senior year at Carver, my father’s eyesight was failing due to glaucoma, and I met this beautiful young woman. At the last minute, I told my coach I did not want to go away. He drove me to Greensboro and I applied to A&T.

OH: The 1969 “Greensboro Uprising” led to gunfire between protestors, police and National Guard troops, leaving an A&T student dead. How did this affect you?

HM: It was such a traumatic event that schools let out early. My brother was in his sophomore year at A&T and my sister was a freshman. When they came home, they talked about the event around the dinner table in profound ways — the fear they had, the military presence was unlike anything they’d ever seen. It was the year after Martin Luther King had been killed, so our talks were buttressed by an ongoing conversation about civil rights, social justice and, ultimately, trust that education was going to be the difference-maker in our futures. At the same time, there was a push to close all the black high schools in Winston-Salem and bus black children to white schools to integrate them. There were demonstrations and protest marches. I participated in those marches, much to my parents’ consternation.

OH: Were you quick to realize your high school sweetheart, Davida, would be your life partner?

HM: Our relationship began to shape everything about the two of us. When she came to A&T, we both began to take maximum course loads, so we could graduate early. The summer before my senior year, we made the decision to get married. To our surprise, our parents said “OK,” and my mother-in-law even asked, “Why did you wait so long?”

OH: Did you feel any reluctance moving from teaching into administrative leadership?

HM: I did. When I was offered the deanship, I realized that I would not be able to teach and advise students directly. But I realized as dean my influence would be on shaping the environment, building the right culture, recruiting the talent and enhancing the academic quality of programs.

OH: You’ve been called an education and business leader in national magazines and recognized as one of the area’s most admired CEOs. How do you explain that?

HM: The toughest person I ever had to please was my mother. She was intolerant of poor performance — even on the modest things, like sweeping the floor or working in the yard. Interestingly, I have been drawn to that type of person throughout my career. All my significant mentors were demanding as hell. I have been so blessed as a result of the passion I feel for what I do. I appreciate the recognition, but it does not define the work I do each day.

OH: How do you hope your sons and grandchildren will remember you?

HM: I want them to remember me as a committed and devoted father. We have three grandchildren, and we just learned that our younger son and his wife are expecting twins, so we’re over the moon about that.

OH: In 2020 A&T received a gift of $45 million, the largest in the university’s history. Is that the beginning or the end of the story?

HM: Very much the beginning. We continue to grow in enrollment, quality of students and investments in research. We’re turning out STEM [Science, Technology, Engineering and Mathematics] graduates in large numbers, along with agriculture scientists, teachers, nurses and social scientists — individuals in high demand nationally.

OH: What do you see for A&T and Greensboro in the coming decade?

HM: New jobs are emerging in STEM and technology, but there is global competition. Consequently, we must position ourselves to attract these jobs to our region. Our university is an integral part of creating that culture. I’m excited about what that means for the future. OH

— Ross Howell Jr.

LAURA WAY

Laura Way, CEO of ArtsGreensboro since 2019, says she learned about development, community building and, most importantly, “about putting your money where your mouth is” from no less than banking icon Hugh McColl (one of North Carolina’s top visionaries) when she was a vice president at Charlotte’s McColl Center before heading the GreenHill Center for North Carolina Art. “I love art, she says. “But I am not a curator. Not an expert on who’s a rising star, or why.” An M.B.A. and prior experience made her a hand-in-glove fit for ArtsGreensboro, where she helped develop the Greensboro Cultural Arts Master Plan, a “roadmap” created in 2018 for the city’s cultural and creative future.

OH: What’s your hope for the arts in Greensboro?

LW: My hope for Greensboro is the arts are not a “nice-to have.” They are recognized as a “need-to have” — for the love of art, how [the arts] play a role in education and health, bring people together to form common bonds, revitalize our economy and make our city and county a destination and model for excellence.

OH: Can you tell us about yourself and what you hope to accomplish?

LW: I arrived here in 2009 to interview as the director of GreenHill, staying with Dabney and Walker Sanders for a week. If you were open to being welcomed, people wanted to welcome you.

[After being hired,] I stayed in the same house in Fisher Park, and it has been my neighborhood. On New Year’s Eve, 2015, I met my boyfriend [developer Andy Zimmerman]. We’re a good couple. He always says, “Do it like you mean it.” Andy wants his imprint to be something special — he’s actualizing it through redevelopment. I want my imprint to be a more creative, vibrant city, where people feel they have a home here and make a good living.

OH: How can ArtsGreensboro help accomplish that?

LW: We need to incentivize people to stay here, move here. The Arts Council was founded to support the EMF, the Symphony and Carolina Theater 60 years ago. People didn’t think about anything outside that. It wasn’t in the gestalt of the times.

OH: You’re unusual in that you have an M.B.A. and found your way into art organizations. Can you speak to that?

LW: Even though I studied economics, I sat in religion and philosophy classes, and they required you to look at everything through the liberal arts lens. We have too many small, emerging organizations that don’t have the capacity to grow. And fewer organizations of color that have no capacity without significant investment. One study found their budget sizes are significantly smaller than in benchmark cities. Everyone deserves access to art. But what I’ve learned over the last two-and-a-half years at ArtsGreensboro is that we have to be careful how we define art. Art is based in Eurocentric traditions that are primarily white. Art takes different connotations, and it is developed in different ways

OH: Can you discuss the arts in a city walloped by a pandemic?

LW: When the pandemic set in, I saw a clear path. It allowed us to lean in and say we can effect change. We launched an artists’ emergency fund and raised $100,000 immediately. We’ve never lived through anything like this pandemic. [Given my background,] I can do the research, crunch the numbers, look at the data. Working with Steve Colyer [of Greensboro Bound], we ascertained the median hourly salary of people working in arts, entertainment and recreation was $11.47. People cannot survive on that! We need a stronger creative sector. If you can’t support creative artists, what’s the point of having organizations?

OH: What did you learn from the pandemic?

LW: The pandemic made me more reclusive. I focused on Andy and my dog, Gravy. Andy bought an RV and we went camping. We took the RV on the Nantahala. At Christmas, we went to the coast. Both of us are public people. But Andy is very interested, very involved with others. I’m more private. My Sunday morning routine, if up at 7 a.m. and alone, is to have a long hike with Gravy. We’ll go to Starbucks and get a coffee for me — Gravy gets a Puppuccino.

OH: What are you reading? Watching?

LW: I don’t sleep — get maybe 4–5 hours a night, which I’ve learned since getting a Fitbit. I think a lot about work. I listen to The Daily. I like podcasts. I watch Jon Stewart.

OH: What were the first 10 years of your life like?

LW: Most of my memories of my first decade before my parents divorced involve my [six] siblings. It was sort of disjointed, and uncertain. So, I invented my own little world. And I became quite insular.

My father remarried, and we all moved with him to Syracuse, N.Y. In fourth grade I got rheumatic fever. That was the year when I stabilized. A year of being nurtured. A year of no drama. It shaped my ability to be with myself and self-isolate. That year shaped who I am today.

OH: What would you tell your 10-year-old self?

LW: Someone told me I wasn’t smart enough; I wouldn’t amount to much. . . . It stuck with me. But I would probably tell my 10-year-old self that it is OK to love and trust. I do love people. I realized growing up in a big family that each of us has our own reality. We compartmentalize our childhood. Later in life, it’s hard to decipher what was our own internal myth.

OH: What do you think Greensboro will look like in 10 years?

LW: In 10 years, [I hope] we are a more connected community — where our college and university students see themselves staying here, our streets and neighborhoods are safer and the talk of failing schools is behind us. And art and creativity are abundant and authentic. And then I will retire. OH

—Cynthia Adams

DONNA BRADBY

An unabashed lover of Greensboro, local theater maven Donna Bradby has owlish vision that swivels easily from past to future — hers and the city’s. At 59, she summons images from her childhood in Greensboro’s Cumberland Courts assisted housing community, then pans to modern-day scenes of artistic activism on Elm Street. With the practiced eye of a storyteller, she relates them with the frisson of someone who knows her way around the stage. She comes by her creativity honestly: Off the clock, her mother was a gospel singer, her father, an actor and musician. Following suit, Bradby is an adjunct professor and director of marketing for the theatre arts program at N.C. A&T State University. She’s also the executive director of the homegrown Touring Theatre of North Carolina, and on the board of Triad Stage. “I feel so connected to this city as an artist, as a woman, as a creator,” she says. “I’m so grateful that this is where I live.”

OH: Can you reflect on the last 10 years in Greensboro?

DB: Greensboro, to me, takes some heavy hits around race. People thinking that we’re ignorant, that the political climate in Greensboro is in turmoil. All of these things, to a certain extent, are true. But on the other hand, we’re resilient. We will change.

OH: So in the past 10 years, there’s been an ongoing tug of these forces in Greensboro, many of them racial?

DB: Yeah, and I don’t think that’ll ever end for us. . . . There will always be some kind of racial tension or divide. And then 10 people will come together and say, “I don’t want to do this anymore. I want to be together.” And a year later, 12 more people will say, “I get it.”

I think all relationships have a push and a pull. We can co-exist. We don’t have to agree on everything. We don’t have to be best friends.

OH: What are some memories from the first 10 years of your life?

DB: I did arts camp at Windsor Center and at Lincoln school. I went to Mt. Olivet AME Zion Church, and I still belong. That’s the first place I ever took a creative dramatics class, in the fellowship hall, and it really shaped me. I loved third grade at Porter Elementary. Mrs. Quillian was the teacher. That was the year we learned cursive. I was the only little black girl, and there was one little black boy in the class. I do remember racial slurs, but I was always clear about who I was. I always came home to a safe space.

OH: Who was instrumental in that?

DB: My Aunt Annie Ruth was my favorite person. She used to say, “Other families are jealous of our family. We’re so good-looking and smart.” And if you told us different, we didn’t understand that. She could see good in a serial killer. She always found something good in people.

OH: Fast-forward to the last 10 years of your life. Can you share an experience that has affected your personal growth?

DB: This story I’m about to tell you is funny, but it’s not funny. When I was in junior high school at Mendenhall, I had a bully. She was an African-American young lady, and that was a tough time for me. Even though I came home to a safe space, I was in that teenager, awkward I-don’t-know-who-I-am stage. I attempted to kill myself with pills because of the bullying. I was so frightened. I said if I ever saw her (the bully) again, as an adult, I was gonna jump on her . . . I ran into her a little over a year ago at the bank. I thought, “OK, it’s going down in the bank. Should I take my earrings off? Should we do it in the parking lot? Security, get ready.” We locked eyes. She came up to me and said, “Donna, you look so pretty. We’re so proud of you. I’ve never been to see one of your plays, but we read about you in the paper.” My ego kicked in. I hugged her and kissed her. I think we exchanged numbers. Then, when she walked out the door, I said to myself, “Damn!”

OH: There it was, right?

DB: I shoulda kicked her ass. What was wrong with me? But she embraced me. It was weird. It was one of the weirdest experiences that I’ve had in the last 10 years.

OH: What shifted for you?

DB: My spirit just opened up. I think everybody wants to be embraced. I always wanted to be friends with her.

OH: And how did you reckon with that experience?

DB: She was a part of who I am now — the courage I have now, the boldness I have now. . . . I believe everyone comes into your life for a reason, good, bad or indifferent, and I want people to know you can get on the other side — and there’s another side to it.

OH: What do you see in Greensboro in the next 10 years?

DB: I see more innovative artistic things happening. I think there’s a tide of more corporate support for the arts here. On the political scene, I think we’re going to be at the center of what’s happening next in a way that’s going to change policies around voting. When you look at the civil unrest and the civil rights in this area — and you look at the people on our city council — the up-and-rising new people who want to make a political stand and have a voice — I think there’s going to be some coming together, some unity. I believe in this city. People like to worry about how long it took for something to happen. It’s happening! Jackson Library (at UNCG) just did an exhibit on gay bars in Greensboro. Come on! I love you, Greensboro! When George Floyd was killed, our artists went downtown and created murals. I believe chaos has to happen. I don’t mean bad chaos. I mean chaos in a way that’s going to wake us up, that’s going to hit us in the face and bring us home.

OH: If you were the director of a play called “Greensboro,” where would you shout “cut” and where would you shout “action”?

DB: I would shout “cut” at the Woolworth’s sit-ins (1960), then I would take up action during Black Lives Matter (2020) because I think they are pivotal points for this city. It’s the same story, give or take some specifics. It’s the same because we took action, we rose up, we were at the forefront, we were bold, we joined the nation. Even the people who don’t believe in it weren’t quiet. OH

—Maria Johnson

MAX CARTER

If you can’t spot him by his Santa Claus beard and ever-present hat — a straw fedora in the summer and a broad-brimmed black lid in the winter — you’ll know him by the lively blue eyes and rollicking laugh that make 73-year-old Max Carter appear to be much younger than he is. A fixture in Greensboro’s Quaker community, he retired from Guilford College in 2015, capping a career of leading campus ministries and religious studies. His specialty: Speaking truth to power. His life is full of examples, from Carter’s own conscientious objection to the Vietnam War and his role as a peacemaker in the Israeli-Palestinian conflict — he visits the West Bank city of Ramallah annually to bring enemies face to face — to his persistent lobbying of local government to support a Quaker Heritage Community. Since retiring, he has written three books and is working on a fourth. He teaches for the Shepherd’s Center of Greensboro and for N.C. State’s Osher Lifelong Learning Institute. Fun fact: When Carter was a freshman at Ball State University in Indiana, he lived on the same floor as David Letterman, then a junior. “He didn’t have the time of day for us mere frosh,” says Carter. “At least my beard is longer than his is now.”

OH: What do you see when you look ahead for Greensboro in the next 10 years?

MC: In so many ways, this city represents speaking truth to power. If we could only bottle it, it could be a gold mine.

OH: An example?

MC: We used to take Guilford students to the Underground Railroad Tree on campus to tell the story about 12-year-old Levi Coffin confronting 85-year-old David Caldwell. Levi Coffin was not yet the president of the Underground Railroad. He was a farm boy of minimal education. This was about 1810, and David Caldwell was the guy in North Carolina. He started the first college and the first Presbytery. He was Princeton educated. He was a patriot of the Revolutionary War and the War of 1812. Caldwell was an enslaver, and he was going to send his slave Edie to Charlotte to be domestic help for their son, who was just married, which meant she would be separated from her husband and family. She took her newborn infant and ran away. They went to Levy Coffin’s family’s farmhouse on Horse Pen Creek, and they were taken in. Little Levi heard this story, and he couldn’t imagine that a minister of the gospel would do this. He said, “I’ve got to confront David Caldwell.” If he blew the whistle on his parents, they could be arrested, and he could be an orphan. But in Quaker culture, if you have a concern that’s rooted in truth, you’re supported. So his parents said, “Sure.” This kid walked seven miles from his home, confronted David Caldwell, and talked him out of it. It’s a remarkable story.

OH: What are some modern examples of this kind of courage?

MC: This city has done that with February 1, 1960 [the start of the Woolworth’s sit-ins]; with the Underground Railroad; with getting Josephine Boyd Bradley to integrate Greensboro Senior High, now Grimsley. She was recruited by Quakers to do that.

OH: How much of Greensboro’s present-day personality is influenced by the Quaker presence in our history?

MC: It has a lot more bearing than we talk about. Williamsburg and Old Salem have capitalized on far less. Could you imagine a walking tour here, where you go from a mass grave of British and American soldiers, to the origins of the Underground Railroad, to the history of integration? My limited vision for a Quaker Heritage Community could be, with the resources of the city, turned into a remarkable tourist attraction.

OH: We have a feeling that your vision of historical tourism does not include a Quakerland with an Underground Railroad roller coaster ride. Or does it?

MC: We used to joke about that: Six Flags Over George Fox [a road through Guilford College], but no. It would violate Quaker simplicity.

OH: Can you reflect on the last 10 years of your life and the significant experiences that have affected your growth?

MC: I retired in 2015, and when you reach a culminating point like that, you look back. People say, “Oh, you’re an institution, you’ll be remembered forever,” and all of that kind of stuff. No. Campus cultures change every three years. There were about 25 different programs I began in my 25 years at Guilford. All but one has disappeared. As I reflected on that with a colleague, he said, “When I was there, I thought ‘I’m creating a future for this college,’ and I’ve now realized I was creating a wonderful present for myself.” That has been a great solace.

OH: What can you tell us about the first 10 years of your life?

MC: My first 10 years of life were spent on an Indiana dairy farm. My father died of a brain tumor when I was 5, leaving my mother with three boys and pregnant with the fourth on an 80-acre farm. My memories are farm work. Herding cows, milking cows, working in the garden, helping with hay, silage, and perfecting the ability to get under a hen and grab all the eggs you can and get out before your hand is pecked off.

OH: Can you think of a formative experience that helped to make you who you are?

MC: I started school at age 5. I was making Ds and Fs. I was not into it. A substitute teacher said take your papers out and design a Christmas tree, bring it up to me for approval of your design, then color it in. It was the first thing I’d gotten excited about. I made this design and decorated it and put Christmas presents under it. I colored it in. I took it up to Miss Allie and showed it to her, kind of expecting a pat on the head. She looked at me and said, “You didn’t get approval for this first, did you?” I said “No,” and she ripped it into shreds and tossed it in the trash basket.

OH: And?

MC: It ruined me for about eight years of education.

OH: Is this why you became comfortable with being anti-authoritarian?

MC: Yes. And that’s why I could never tear up, in any way, student papers. I can see every moment of that first-grade experience. I could never do that to a student. I was probably easier than I should have been as a college professor. OH

—Maria Johnson

O.Henry’s 10 for 10

Our 10-word short story winners

Back in January, we announced a short story contest in honor of our namesake, William Sydney Porter. As in, really short.

“Tell us a story in 10 words,” we challenged, adding that winning entries would appear in our 10-year anniversary issue.

And here we are.

It turns out you can say a lot with just 10 words.

Many readers responded with short stories that surprised and delighted us in ways we could not have imagined. Although it was nearly impossible for us to agree on winners (and please don’t ask us to rank them), the following are among our staff favorites. Thanks to all the clever souls who played along.

Figs bloomed. Leaves faded. Donating last year’s clothes. Contact Eve.

–Kathy Ross

Kathy Ross of Danville, Virginia, is a reading and English tutor who spends weekends with her husband in search of coffee, vintage books and issues of O.Henry in and around Greensboro.

Froggie, arriving in a poinsettia, joined the church Christmas pageant.

–Tom Black

Tom Black lives in Southeast Greensboro, where he is spending his retirement reading and fishing.

Sobbing, paddle resting on his lap; dark water, we drift.

–McCabe Coolidge

McCabe Coolidge is a community potter in Greensboro who has given away hundreds of bowls to nonprofits during the pandemic.

He looked, he lied. He never thought about it again.

–Mia Malesovas

Mia Malesovas is a lifelong learner and educator who lives in Summerfield.

Dad loved sunny sides. Mom fried hard. Broken shells. Done.

–Mike Cecil

Born in Greensboro, Mike Cecil now lives in Summerfield where, retired, he writes and creates. He recently mastered the art of cooking in cast iron and says he can also make the perfect hard-boiled egg.

Green sky

Howling train

Closet quick!

No room for Lucky

–April Pilhorn

April Pilhorn of Browns Summit is an explorer who appreciates all things art and nature. She is a collector of moments, not things.

She smiles as her husband drinks. Poisoned tea tastes sweet.

–Kay Cheshire

Kay Cheshire retired from the medical field and lives in Greensboro.

She left the bear and her walking staff behind her.

–John Adamcik

John Adamcik lives in High Point with his wife, Jeanneen, and family. He is a part-time minister who works in HR for a nonprofit human services agency.

O.Henry About Town

Photographs By Lynn Donovan and Bert VanderVeen

The spirit of William Sydney Porter, aka O.Henry, is alive and well in the city he once called home. In fact, on a recent autumn morning, several of his characters were spotted downtown wandering around in a world that must have been deeply familiar and yet perplexingly futuristic. Where were the streetcars? The wide-brimmed hats and spatterdashes? And what on this green and spinning planet was a selfie? Well, folks, they would soon find out. “The true adventurer goes forth aimless and uncalculating to meet and greet unknown fate,” quoth O.Henry. That’s for sure. Please enjoy a few snapshots from their whimsical escapades about town.

Can a lady get a drink around here? A pumpkin spice what? Sure. While two oat-milk lattes are being whisked to frothy perfection behind the bar of The Green Bean coffee shop, this gossipy pair discovers that they have scored front row seats to the best people-watching on the block. Would you look at that hemline! How deliciously scandalous! How utterly cosmopolite!

Of all the places they could go, who knew that the road of destiny would lead this pair down Elm Street to a place called The Selfie Spot? Inside, a wild and glittering world of vignettes beckoned. Jim pulled out his gold pocket watch to check the time, then shrugged. “What does it matter?” he said to Della, who gave her glorious locks a playful toss before asking the bright-eyed lady behind the counter, “What’s an iPhone?”

Something about the old Fordham’s Drug Store made the O.Henry troupe feel both dizzy and elated. It was almost as if it was déjà vu all over again. As if this place were somehow a part of them. And was anyone else suddenly craving a soda?

What happens if you miss the train? Something called Blue Duck. Don’t knock it until you’ve tried it — but do hold on to your hat.

Well, well. Look who got caught canoodling in The Selfie Spot’s ball pit. Or is that, in fact, a time machine?

A special thanks to An O.Henry Celebration: Stories & Song — formerly 5 By O. Henry — for breathing O.Henry’s short stories to life through its theatrical vignettes year after year. Stay tuned for September 2022 performances at Well-Spring’s Virginia Somerville Sutton Theatre.

Poem November 2021

Quarantine Haircut

I’ve had hundreds of haircuts over the years

but never one as intimate as the one Julie

gave me yesterday, mid-quarantine, and my

hair standing up and out of control and when

she could take it no more she said sit down,

Bozo. I happily complied, always eager for

her touch. She stood over me cutting, clipping,

and buzzing and I could feel her legs on mine,

her forearm brushing my ears. But it wasn’t

the physical touch as much as the proximity,

breathing the same air like we used to do back

when the sight of each other would result in

clothes flying through the air, naked bodies

moving together in rhythm, but this was a haircut,

scissors, a misused beard trimmer, a memory of

what was once there. When she asked why I was

crying, I said Some hair must have irritated my eyes,

and she didn’t press, only wiped it away, said

you’re a fool and she was right once again.

—Steve Cushman

Wandering Billy

Content May be Graphic

How discovering artist Christopher Williams was sort of a perk of the job

By Billy Eye

Toward the end of middle school we went on a field trip to Virginia to go whale watching. I don’t remember any of us seeing anything through the rain-smeared windows of the cabin. Most of us were sitting in the boat, drinking hot cocoa. But it was a trip where we got to stay in a hotel with our friends, away from parents, so that’s what mattered. I didn’t do much, certainly didn’t climb across balconies to sneak into girls’ rooms or sneak alcohol into my room like some of my peers (and one of my roommates). I don’t know what the chaperones expected, as there was zero chance they’d be able to monitor all of us. I’d like to think we were innocent as my son is approaching the age I was, but I know from the stories that a lot of that innocence was long gone.

— An excerpt from The Letter Journal

One afternoon, while tending bar at Parts Unknown: The Comic Book Store, I happened upon a 5-by-5-inch graphic novel that blew me away with its raw, emotionally charged storyline. The Letter Journal is one man’s illustrated tale about growing up in Greensboro, leaving for college and becoming a working artist and father — all the while plagued with depression and gut-wrenching insecurities. Which pretty much describes the trajectory of every true artist I’ve ever come in contact with. This book drills into where those feelings of inadequacy originate, wrapped in a deeply personal narrative.

The Letter Journal is written and illustrated by Christopher Williams, whose family moved to The Gate City from Florida when he was a child in 1986. After attending App State in 1998, Williams moved to Durham, where he lives today.

“It’s not standard comic-book fare,” Williams explains, “especially in that it’s not strictly sequential.”

But experimental? Absolutely.

Drawing from personal experience, the artist mused, “What if I just start attaching different images to paragraphs of a story?” Which brings us to the aforementioned whale-watching trip.

“Would it be safe to say that you have a permanent case of teen angst?” I venture.

Williams laughs.

“I have maybe an evolving sense of angst,” he says. “I thought that it would go away at some point . . . But yeah.”

As for the inspiration for The Letter Journal?

“John Porcellino makes a comic called King-Cat,” Williams says. “He’s been publishing that for, I think, 30 years, and it covers a lot of what he’s been through. Also, Adrian Tomine published a book last year that covered his experiences as a freelance artist, and that really resonated with me.”

Williams has published ten graphic novels in two-and-a-half years. Most of them come with a suggested soundtrack to help bring the reader “into the kind of mood that I want them to be in to experience the book.”

For The Letter Journal, he recommends the song “Claws” by post-rock/post-hardcore band Shipping News.

Radio, one of Williams’ latest books, was made possible with support from a Durham Arts Council grant.

“If I had the opportunity to go and speak with my younger self, what would I say? How would I handle that?” he says, speaking to what sparked it. “My son, Seamus, is in eighth grade now. I was thinking about what it would be like to be my son’s age.”

Williams’ family still resides in Greensboro. “I’ve started taking my son around town and showing him around. ‘This is my old high school, Page. That’s where the art room burned down . . .’”

Wait, what?

“The story that I had heard was that someone broke into the school and tried to burn it down. And the art room was in the middle of the campus, so they set it on fire. It meant the art students had to go to the library for a semester. It didn’t affect anybody else.”

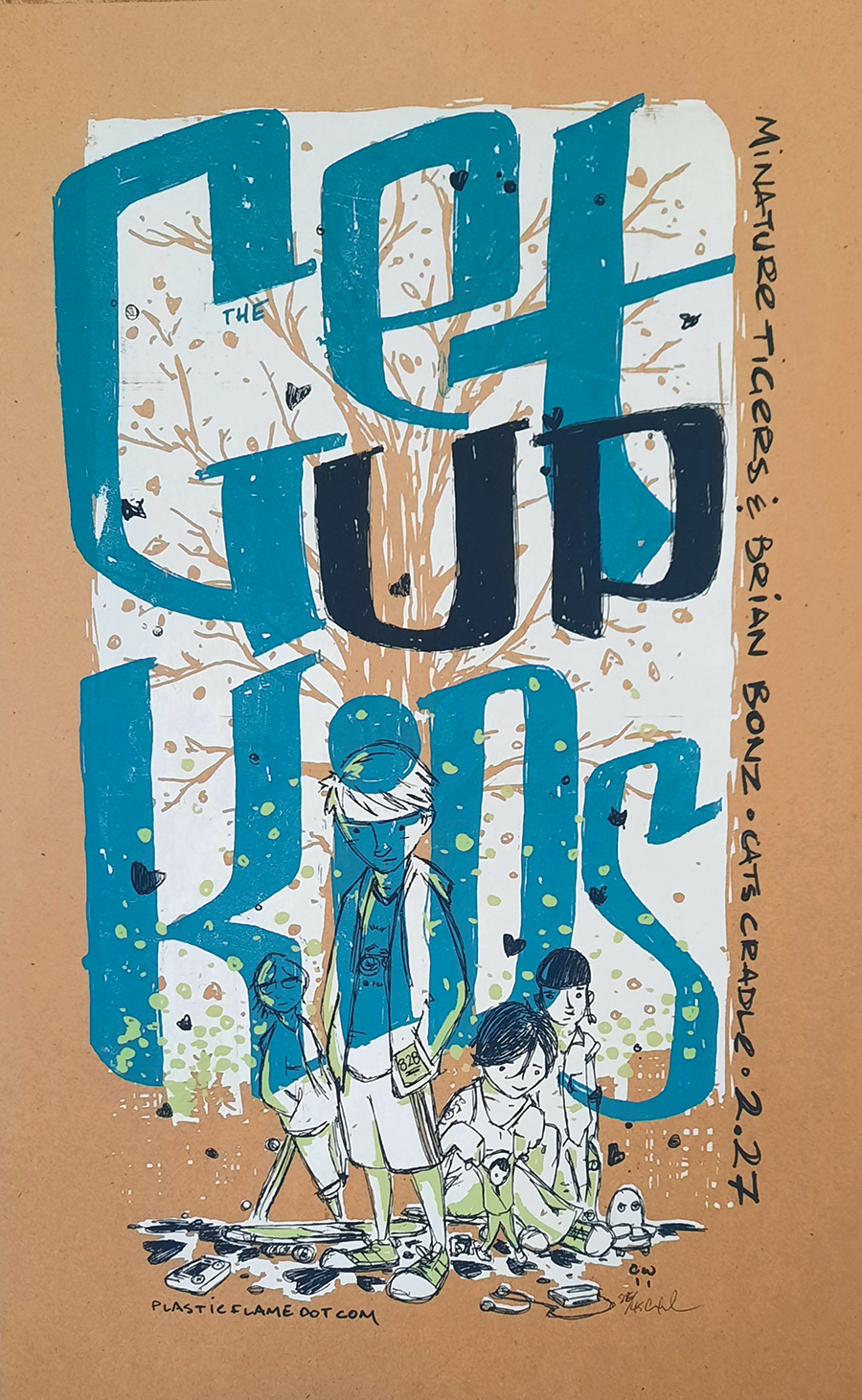

During the lockdown, Williams concentrated on creating books. But his real passion, his raison d’être is creating gig posters for bands playing at Cat’s Cradle, the iconic music venue in downtown Carrboro. Truthfully, his posters are some of the most amazing designs I’ve ever seen. (Keep in mind that in a previous life I was tasked with creating artwork for big budget Hollywood blockbusters. I’ve worked with some of the biggest names in illustration and photography. Williams’ work is right up there with the best.)

What makes these posters so remarkable is that for the longest time they were strictly silk-screened, not fashioned from pixels.

“When I started, I thought computer art was going to be a fad,” Williams told me. “And I was like, ‘No, no. That’s nice that people are using Photoshop. That’s not my thing. That’ll go out of style.’”

Instead, he would draw and letter everything by hand, creating color separations with sharpies on tracing paper.

“A couple of years ago, I started to change things up by going completely in a different direction and began collaging illustrations digitally. Now it’s a mix.”

Since 2003, he’s personally screened around 1,000 works of art for Cat’s Cradle. Imaginative, fluid designs for seminal musical artists like The Get Up Kids, Superchunk, Pedro the Lion, Holy Ghost Tent Revival and The Lemonheads. “I’ll get contacted by Cat’s Cradle with a list of bands that are coming through. And I’ll email back, ‘Hey, if no one is doing that band, I really want to do it,’” Williams says.

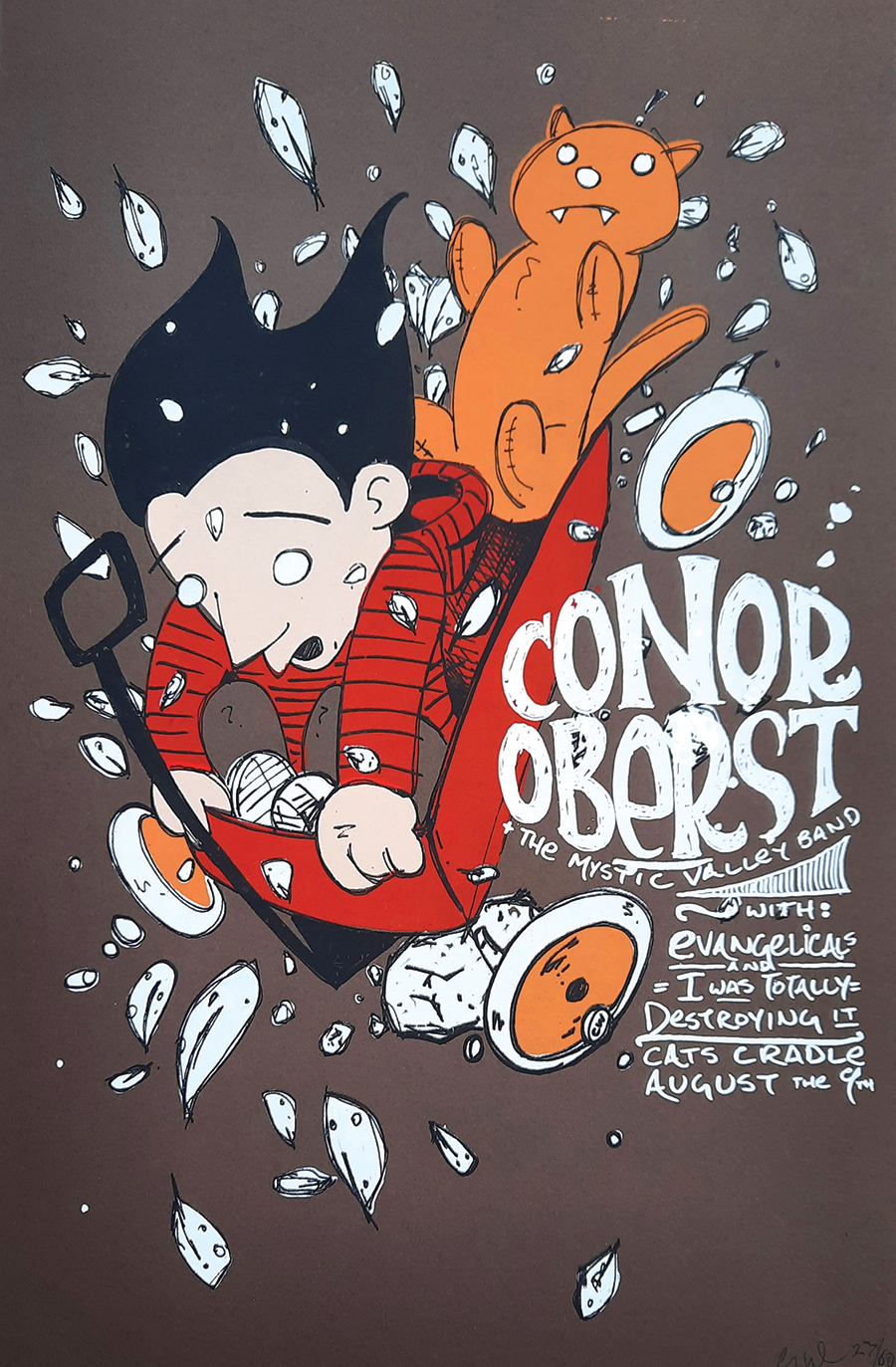

One of my faves is a poster for singer/songwriter Conor Oberst: a rollicking juxtaposition of Calvin and Hobbes-like imagery, conveying a zany joy that stands in stark contrast with the performer’s melancholic but melodious musings.

“It’s important to me, and I know it’s important to Frank [Heath] — the owner of Cat’s Cradle — that there’s this visual representation of an eve

nt,” Williams says. “That someone can go and have this great time — maybe it’s their first date or something — so they rip the poster down off the wall of the club and put it up in their house and have this thing that they can always remember.”

Improbably, he recently created a series of 12-page screen-printed “short story” event posters.

“It’s fun to try and line all that up, so the pages are lined up exactly.”

Williams continues: “With not having a lot of gig posters [last year], it’s been a nice way to challenge myself in a new way.”

Christopher Williams’ books, T-shirts, skateboards and 100 or so vintage band posters are available at his publishing company, plasticflame.com. Spend an hour immersing yourself in what amounts to a timeline of cutting-edge musicians who provided the soundtrack for a couple of generations at least. OH

Billy Eye, who wrote a bi-monthly column covering the East L.A. music scene from 1980–83 (the source for his book, PUNK), is OG — Original Greensboro.

Birdwatch

Turkey Time

A surprisingly wily wild bird

By Susan Campbell

Shorter days and cooler nights have many of us thinking about the holiday season. Thanksgiving is not that far off — and that means turkey. Most of us look forward to feasting on the tender meat of this domesticated, large member of the fowl family. But its wild ancestors are a far cry from the bird we prepare on the fourth Thursday of November each year.

Anyone who has had the opportunity to taste a “real” turkey will tell you that there is no comparison. But hunters who pursue the wild birds are far more often skunked than successful. Turkeys seem to have a sixth sense when being called or decoyed in. Fooling one of these birds to get it within range is one of the biggest challenges bird hunters (or photographers, for that matter) face.

The wild turkey was very nearly our national bird. It is, in fact, the only bird species native to the United States. Benjamin Franklin nominated the turkey for this honor but it lost in Congress, by only one vote, to the bald eagle back in the late 18th century.

Although the cultivated variety is completely white, skittish and not very bright, forest-dwelling turkeys are glossy black, wary and rather agile for a bird with a wingspan of over 5 feet. They are typically found in mature forests with clearings but take advantage of open fields as well. Turkeys forage on a variety of food, including insects, small berries, seeds and buds. Interestingly, one of their favorite fall foods, acorns, are often abundant in our part of the state.

Individuals are well known to associate in large flocks of 50 or more birds. In the early spring, older males will attract and attend to and defend a flock of several females. At this time, they can be heard gobbling and strutting in their characteristic puffed-up posture. Only during the early part of the breeding season, in April and May, are the birds solitary. Once the chicks hatch and reach about 4 weeks of age, hens will gather together with their young and form new aggregations.

In the early 1970s, there weren’t many more than a million turkeys on the landscape. Persecution and habitat alteration had resulted in dramatic reduction in the population. Now, throughout not only the United States but parts of southern Canada and northern Mexico, there are seven times that many.

Here in the Old North State, turkeys can be found in almost every county. In recent years, both the Triad and Triangle have experienced an influx from the Uwharrie Mountains in the west as well as from the inner Coastal Plain to the east. It is not surprising that these big birds show up to take advantage of seed around bird feeders and forage in grassy vegetation along our roadways, as well as looking for tender vegetation and insects in agricultural fields across the area. So, keep your eyes peeled — you, too, may spot one, or more, of these majestic birds here in central North Carolina. OH

Susan Campbell would love to receive your wildlife sightings and photos. She can be contacted at susan@ncaves.com.