The Airing Of An Artist

A Greensboro gallery reveals a long-hidden cache of work by

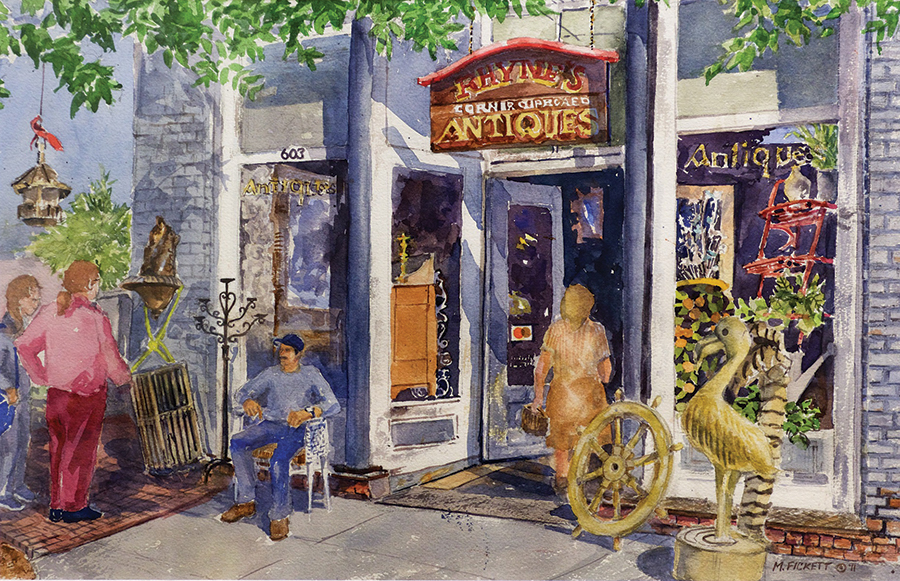

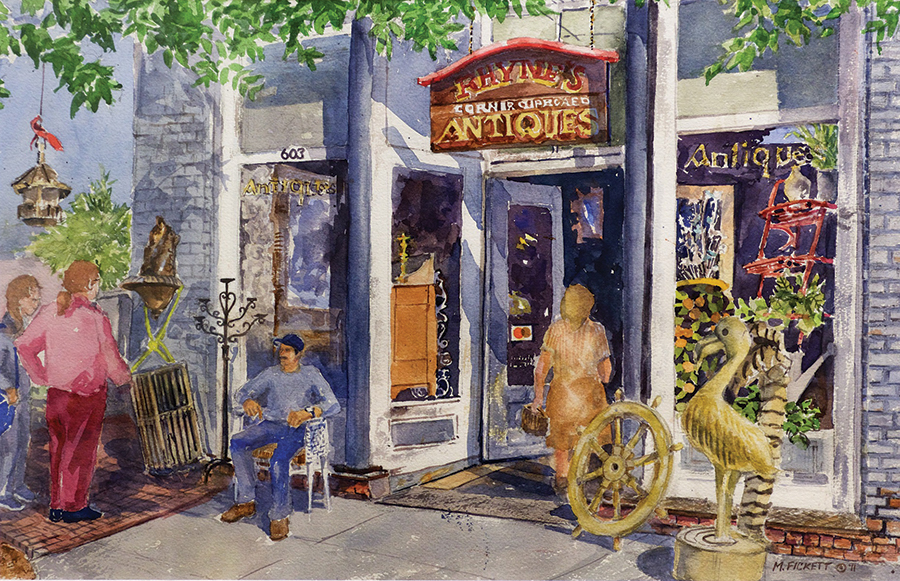

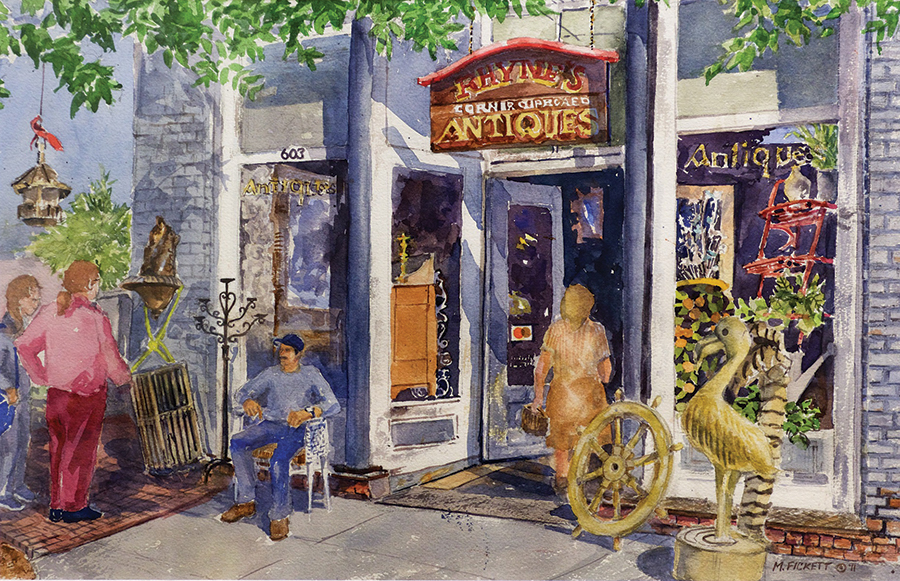

beloved streetscape artist Maggie Fickett

By Maria Johnson

The Center for Visual Artists, a nonprofit gallery in downtown Greensboro, usually promotes the work of emerging artists.

But next month, the gallery will spotlight an artist who emerged a long time ago: 89-year-old Maggie Fickett, who painted Greensboro streetscapes and landmarks for three decades — in the 1980s, ’90s and early 2000s — before returning to her native Maine.

Why mount an overview of her work now?

Because it’s a shining example for up-and-coming creators to follow, says gallery director Corrie Lisk-Hurst.

“We were blown away,” says Lisk-Hurst, recalling the first time she and gallery manager Devon McKnight laid eyes on a trove of Fickett’s work that her family had stored in Greensboro, hoping to show and sell it one day.

Viewing more than a thousand pieces, McKnight and Lisk-Hurst were struck by Fickett’s technical prowess and by her embrace of different media, styles and subjects.

Most of all, they were impressed by Fickett’s faithfulness to her muse. She painted every day.

“It’s important for us to say, ‘Look, this person had a lifetime of making art. Maybe she wasn’t thrilled with every single piece, but she was committed.’ It’s really about practice, like having yoga practice,” says Lisk-Hurst. “If you’re doing it every day, you’re more likely to get in the flow at the right time and get those spurts of genius.”

The public can see those transcendent moments in Maggie Fickett: Living in Plein Air, an exhibit built on more than 75 framed works — mostly watercolors — and hundreds of unframed pieces sorted in bins.

The show opens April 21 and stays up through June 14.

All works will be for sale, and 60 percent of the proceeds will go toward caring for Fickett, who lives in a memory-care center.

“Alzheimer’s is a terrible thing,” says Debbie Fickett, who is married to Maggie’s nephew Bob. The couple moved the artist to Maine in 2014 after becoming concerned about her safety.

This magazine’s story about Fickett’s departure and the raft of work remaining in Greensboro (See www.ohenrymag.com/ficketts-charge) caught the eye of Laura Gibson, who curates revolving art exhibits at Greensboro’s Center for Creative Leadership.

Gibson had met Fickett and owned one of her paintings. Her employer, CCL, also held several of Fickett’s works in its permanent collection.

Gibson knew the Center couldn’t accommodate a large-scale exhibit with a lot of walk-in customers, but she still wanted to help.

She contacted Fickett’s family about organizing a show of Fickett’s work at another venue. (Full disclosure: This writer also assisted in getting the show off the ground.)

Last year, Lisk-Hurst and McKnight offered the CVA gallery in the Greensboro Cultural Center — the very same space where Fickett had shown her work 20 years earlier.

Back then, the gallery was operated by the Greensboro Artists’ League, a forerunner of the CVA, and Lisk-Hurst was a part-time curator.

She remembers Fickett.

“Personally, it was cool that she was someone I’d crossed paths with,” Lisk-Hurst says.

Her CVA colleague McKnight agreed that exhibiting Fickett’s work — including her studies, sketchbooks and photographs — would fit the nonprofit’s mission.

“Most gallery shows don’t show the artistic process, just the final product,” McKnight says. “This is valuable because it lets us see how she’s approaching things, like mixing colors and using the back of paper.”

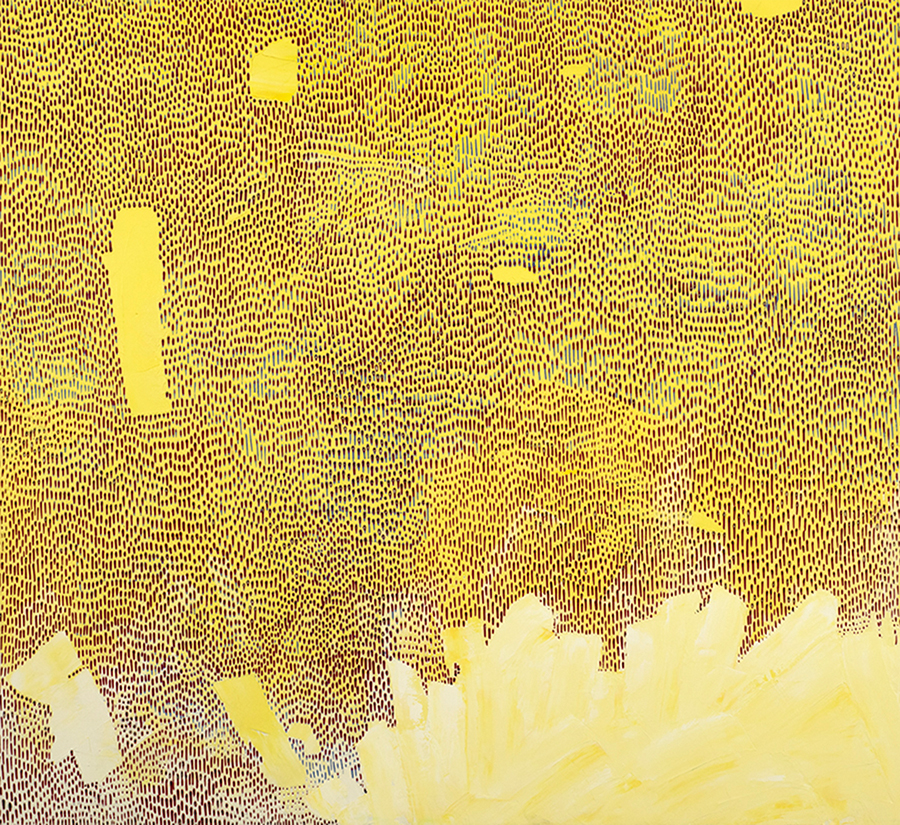

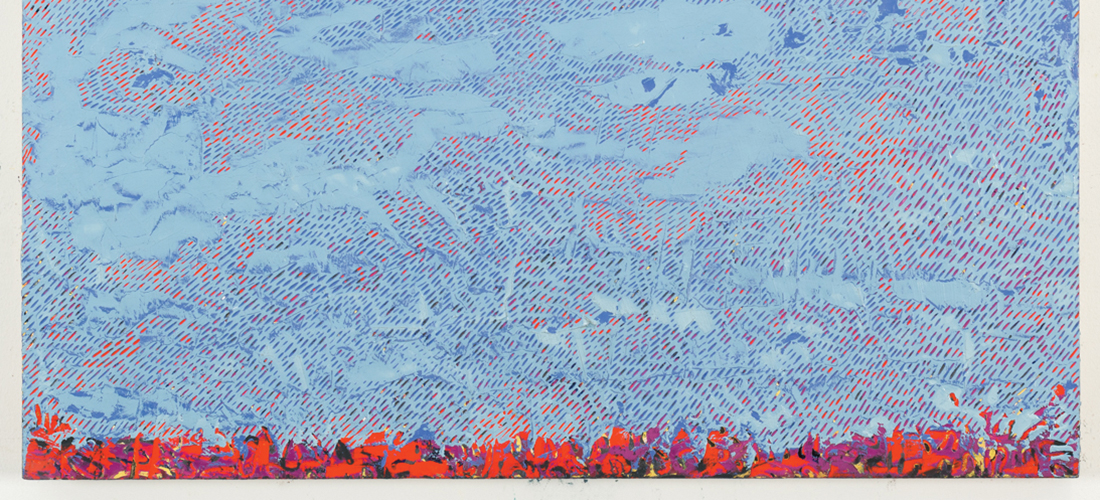

The show also will demonstrate Fickett’s range. She could pen a cartoon-like character; chalk moody landscape; stamp a woodcut print; glue together a satirical collage; or dip a brush in watercolor to record a quaint storefront. Occasionally, she dabbled in acrylic paint.

“That’s what great artists do: They play with things,” Lisk-Hurst observes. “They look at something and they’re like, ‘Huh, what can I do with this?’ ”

Fickett’s creative evolution began in her teenage years. Born and raised in South Portland, Maine, she was working in the laboratory of a Catholic hospital when nuns noticed and encouraged her artistic ability.

With limited support from her family, Maggie moved to Boston and trained in commercial art. She worked for a Boston advertising agency before moving to Greensboro, on the advice of a friend, in 1979.

Here, she gave up the regular paycheck of agency work for the more tenuous income of a self-employed artist.

She was primarily a watercolorist, but years of illustrating gave her the confidence with pen and ink. Balancing sharp details with softer suggestive

lines, she snared the physical and emotional elements of her subjects.

Her bread and butter came from doing commissioned portraits of people’s homes.

She also did pen-and-ink drawings of local landmarks, made prints and sold them for $10 each. For $40 more, she hand-colored the prints.

Her subjects included the historic F.W. Woolworth store; the first Ham’s restaurant; The Boar and Castle restaurant; Yum Yum Better Ice Cream; the Carolina Theatre; Castle McCulloch; War Memorial Stadium; and numerous fire stations, churches and local colleges.

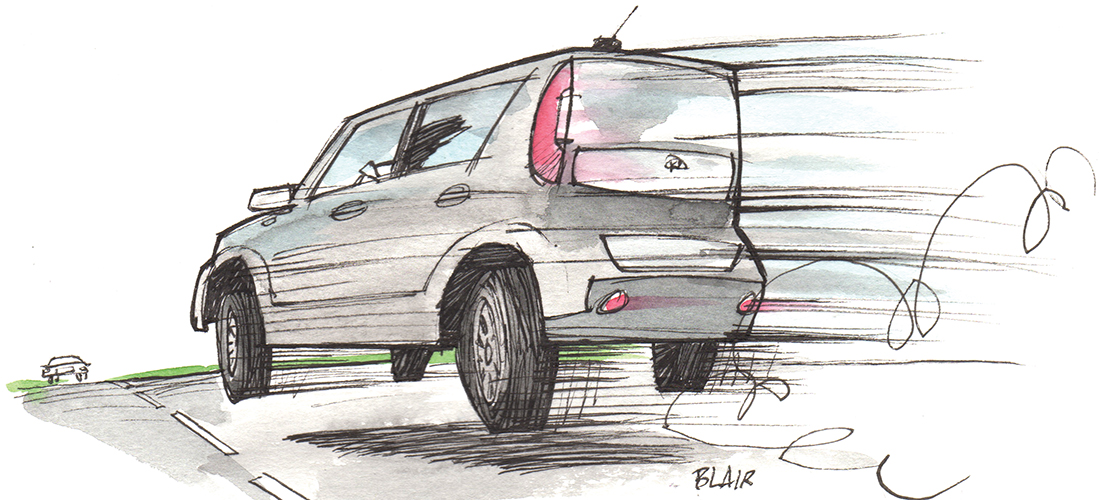

Fickett specialized in streetscapes, working on location, en plein air, popping her easel and umbrella-shaded stool on sidewalks and hillsides.

A favorite locale was downtown Greensboro, where she documented everything from crane-studded construction along North Elm Street to the railroad bridge and antique shops of South Elm Street.

She found inspiration in natural settings, too. The Greensboro Arboretum, the Tanger Family Bicentennial Garden, the Bog Garden and Country Park were frequent subjects.

She loved her own backyard. She painted dozens of scenes around her home on Mayflower Drive near UNCG.

Often, she picked flowers and vegetables, brought them inside, arranged them and preserved them in still lifes.

She painted her cats with nuance and affection.

“Everything was fodder for her,” says Lisk-Hurst. “It didn’t matter if it was a construction site, or a cat lounging on a chair, or a person running on a trail. Everything was worthy of observation.”

Who needs smart phone tracking apps? Exhibit goers can trace Fickett’s movements by looking at her work.

When she lived in Boston, she painted the Charles River, Boston Common and Beacon Hill.

When she moved to Wilmington for a couple of years in the late ’80s, she painted Front Street, Chandler’s Wharf, the Cape Fear River and Wrightsville Beach.

When she traveled with friends to Bermuda, she set down the white roofs and sapphire water.

When she made trips to see pottery in Seagrove, or rolling farms in southern Virginia, or the carousel in Burlington, or the state fair in Raleigh, she painted.

When she returned home to the rugged coast of Maine, she painted.

When she visited friends in Jamestown, cheek-by-jowl with Greensboro, she painted Jamestown.

Works depicting all of these places will be for sale at the exhibit. Prices will range from $10 for small, unframed works to hundreds of dollars for large framed pieces.

Organizers hope the show will draw people who feel connected to Fickett’s subjects.

“Sure, you can buy pieces online or in a retail store, but they don’t have a story. And you’d pay more in those places than you would for some of this original, really high quality work,” Lisk-Hurst says.

In addition to the show and sale, organizers plan an opening party, a panel discussion of Maggie’s life and work, a roundtable on making a living as an artist, and a painting class that guides participants through a Fickett-inspired scene.

Maggie’s health won’t allow her to attend the show. But her spirit will be here, says Debbie Fickett.

“Her heart will always be in Greensboro.” OH

For more on the exhibit, go to www.greensboroart.org

Maria Johnson is contributing editor of O.Henry magazine. She can be reached ohenrymaria@gmail.com.