Extra, Extra, Read All About It!

While most journalists struggle, Sally Nagappan has found a niche

By Maria Johnson

Like most writers, Sally Nagappan is curious. She asks a lot of questions, and sometimes the answers light a fire in her — a passion for truth that passes through who-what-when-where-and-how.

In other words, she’s a journalist.

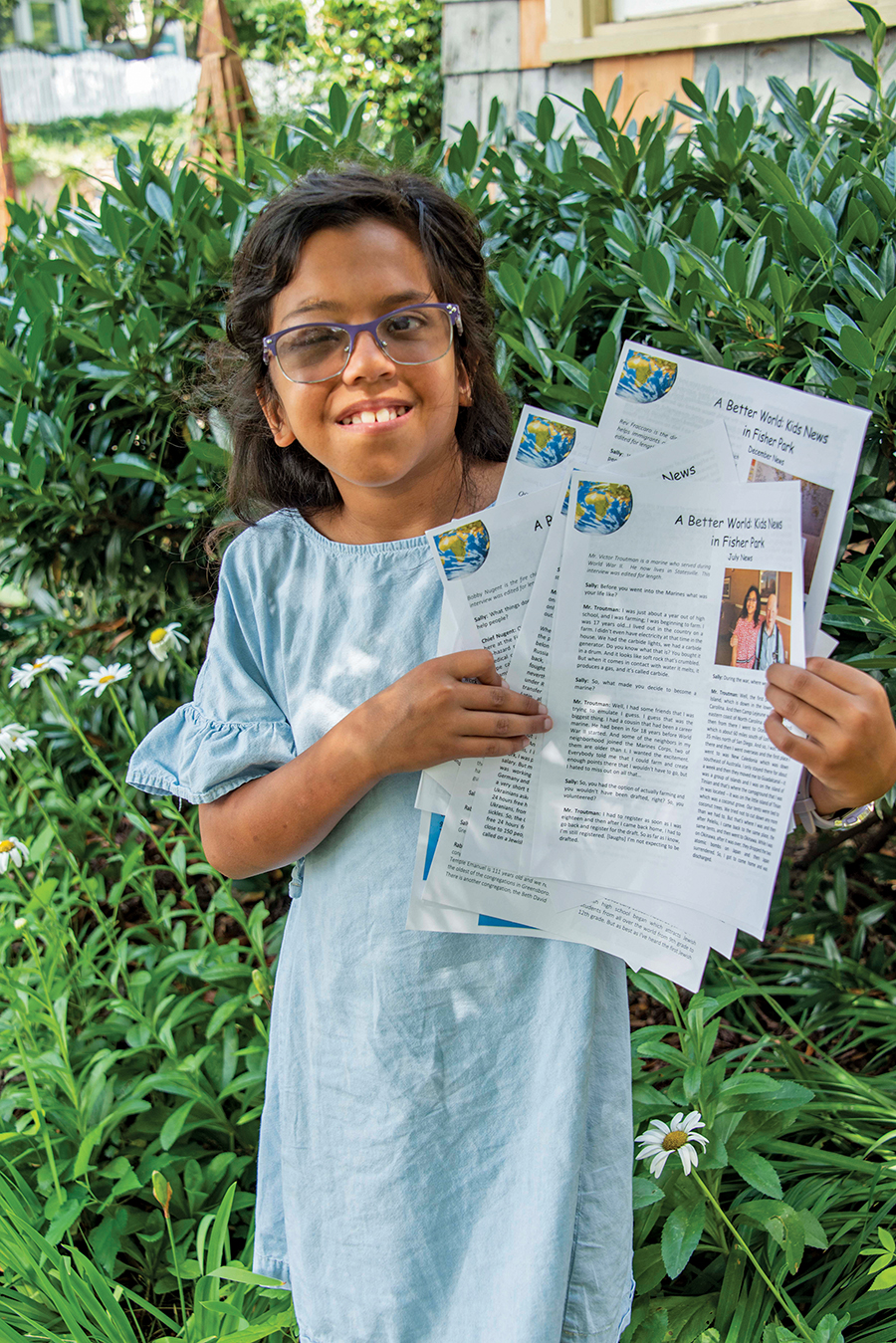

Two years ago, Sally, now a rising fifth grader at Irving Park Elementary School, started a neighborhood newsletter called A Better World: Fisher Park Kids News.

The first issue — printed on a single sheet of paper, front and back, in full color — came about after Sally and her mom, Sarah Jordan, stopped to talk to a neighbor who’s a teacher.

The conversation turned to immigration. Sally, whose paternal grandparents came to the United States from India in 1970, jumped into the front-yard discussion about modern-day newcomers.

“We decided we should write about this, and so we did,” says Sally, with 11-year-old matter-of-factness.

Sally and her neighbor teamed up to create the first newsletter. In the lead editorial, labeled “Sally’s Opinion,” the fledgling scribe supported legal immigration.

“I think maybe they should have documents,” Sally wrote.

But she challenged readers to have compassion for refugees and illegal immigrants.

“How do you think it would feel if you had to leave your country because it was dangerous or you needed a better job but you were undocumented?” she asked.

With fifth-grade simplicity, she summed up a complicated issue that stymies older, supposedly wiser heads.

In neighborhood news, she investigated water that was flooding the streets around her house. She found out the city had hired a contractor to flush out water pipes that had not been cleaned in 60 years.

“Look at all this wasted water! But really they were flushing the pipes,” she wrote under photos of the repairs in progress. In lighter news, she included a short feature about Halloween.

“There was a zombie wandering the streets. He chased people but he wouldn’t hurt them because he was a nice zombie,” she reported. “It was tiring toward the end but all in all it was fun.”

Sally and her neighbor assembled the paper. Sally drafted her dad, Suresh, to print them on his office printer and help with distribution of the first issue in November 2017.

“I was the paperboy,” he says.

After that, the bulletin became a family enterprise. Sally’s dad, who wrote for his high school newspaper near East Lansing, Michigan, lent Sally his cell phone to take photographs. He helped her lay out the newsletter on a laptop. Together they walked door-to-door, delivering the sheet to people living on Isabel, Hendrix and Olive streets in the northeast quadrant of historic Fisher Park.

The second issue appeared in March 2018 — “I tried to make it monthly, but it was too much,” Sally says — and she settled into the current format: a question-and-answer session with someone in the community, plus an editorial and a photo feature.

Her interviewees have included Officer R.C. Dixon of the SCALE (School- Community Alternative Learning Environment) School in Greensboro; Rabbi Andy Koren of Temple Emanuel; her grandmother, Saku Nagappan; Rev. David Fraccaro, executive director of FaithAction International House; Greensboro fire chief Bobby Nugent; Holocaust survivor Hank Brodt; and, most recently, Sally’s great-great-uncle Victor Troutman, who was a Marine in the Pacific theater in World War II.

With help from her father, Sally picks subjects whose views are sometimes neglected.

“They don’t get their voices heard a lot,” she says.

Maybe because she’s so young, Sally has a way of bringing out her subjects’ vulnerabilities. Officer Dixon confessed to her that sometimes police are just as scared to speak to people as people are to speak to them.

Sally doesn’t hesitate to ask tough questions.

“Is a wall really that bad?” she asked FaithAction’s Fraccaro on the subject of adding more wall along the southern border of the United States.

“We think there are smarter ways and more affordable ways to monitor the border,” replied Fraccaro.

The reason Sally likes to interview older people, she says, is to document their experiences while there’s time.

“It’s now or never,” she says candidly.

Suresh Nagappan says the project reflects his daughter’s determination.

“I’ve always appreciated Sally’s work ethic,” he says. “She dives in and sticks to it.”

Her ability to ferret out subtleties and yet understand the big picture makes her a good journalist, he adds.

“I think she does a great job of not reducing people to a job or activity or event in their life.”

So far, through eight issues, readers have responded favorably.

Sally’s across-the-street neighbor, Marianne Gingher, a professor of English and comparative literature at UNC-Chapel Hill, sends notes of support regularly.

“I like getting fan mail from her,” Sally says. She perches on a comfortable chair in the lobby of her editorial office, also known as the living room of the family’s bungalow.

“I’ve lived in this house all my life,” Sally says, tugging at the sleeve of her cardigan. When she’s not churning out copy, she explains, she likes to swim for fun and play violin and ukulele. She enjoys crafting with beads.

A few feet away, her brother Will, who’s 8, wiggles on a couch between his parents.

“My dad wants Sally to ask me to write an opinion piece about school lockdowns,” says Will.

The look on Sally’s face says she’s heard this story idea before, and she’s not sold on it.

“Maybe the next issue,” she offers.

Will presses. He brings up her refusal to run a free ad for the leaf-raking business he operates with a buddy.

“I don’t want to do advertising,” she says cleanly.

The kid is a born editor.

But she nixes her current gig as a career.

She’d rather be a doctor, like both of her parents are, or maybe help immigrants by working at FaithAction, she says.

Still, her stint in journalism is teaching her a few things.

No. 1, it’s not easy work, she says. It takes a lot of planning to conduct interviews and put together an interesting paper, especially when your news hole has doubled from two to four pages.

Also, she’s found out, being a reporter introduces you to all kinds of people, including people you don’t agree with.

In Sally’s opinion, that’s not a bad practice.

“It makes me a better person to listen and learn,” she says. OH

Maria Johnson is a contributing editor of O.Henry. She wants to be like Sally Nagappan