All the yard’s a stage in Shellie Ritzman’s blooming world

By Maria Johnson

Photographs by Amy Freeman

Shellie Ritzman is having a vision.

Right here, right now, standing in the dirt beside the brand new, tin-roofed workshop in her backyard in Kernersville.

She’s waving her hands. Her voice and her body are animated.

She can see the future. She points to it.

See? There’s a bright floral design — one she has painted — on the exterior wall of the workshop.

Below the design, on the ground, there’s a bench. A long bench.

The bench is filled with Boho pillows.

“You can seat probably six, seven, eight people,” she says.

Her customers will mug for pictures there, she says. Young people, especially. They want pictures to post on social media to show people their memories before they’re even memories. That’s why Ritzman has painted cheerful background graphics on other walls around the property.

But back to the vision.

Gravel will go here, Ritzman says, brushing broad strokes with her palms to the ground.

Her hands fly up, and she draws lines overhead.

Bistro lights will go here.

Anchored by a tall post here.

And, of course, she says, her fingers playing arpeggios in the air, the space will be surrounded by gorgeous flowers and plants.

“There’s so much to do,” she says, turning on the heels of her sporty flip-flops.

Somewhere, there’s a stopwatch ticking, and Ritzman — who goes by Shellie Watkins Ritzman professionally — hears it loud and clear.

“I’m always thinking of stuff,” she says. “Always.”

Her feat isn’t so much the thinking, though.

It’s the doing.

The actions that make her vision real.

In the last two years, this semiretired executive assistant has created, from thin air and good dirt and more than a little sweat, My Garden Blooms, a homespun enterprise that wraps a cut-flower business — rooted in a backyard labyrinth of raised beds— around cozy staging areas where area artists and craftspeople conduct flower-friendly events for paying customers.

For example, later this month Ritzman will host a class called Board and Bloom Bar. For 65 bucks a head, a dozen people will gather in the breezy outdoor room that juts from the back of her ranch-style house to learn how to make a charcuterie board, the 21st-century term for a spread of meat, cheese, nuts and other antipasto.

Whitney Chaney, owner of Gather & Graze Co. in Winston-Salem, will lead the session. Participants will sip botanical teas and lemonades and nibble from their own charcuterie cups. At the end, students will make a small bouquet from a selection of cut flowers to take home.

Next month, Kiley Duncan, who owns Tea + Toast, another Winston-Salem business, will show people how to make cocktails and mocktails using loose-leaf teas and botanicals. Customers will, of course, make themselves a parting bouquet. They’ll also have a chance to buy some of Kiley’s handcrafted bitters and elixirs.

Ritzman’s calendar stretches on, year-round, with tutorials on candle pouring, rock painting, flower pressing, wreath making and dried-flower arranging.

The events are good for her collaborators and for her. They raise the visibility of Ritzman’s property — which is available for private events, too — and they spotlight her primary stream of income, subscriptions to cut-flower bouquets that Ritzman wraps in brown paper and delivers weekly to pick-up points near her subscribers.

At the moment, her distributors are Cake and All Things Yummy in Kernersville and Lavender and Honey Kitchen in Winston-Salem.

“Hopefully they’ll buy a cinnamon roll and a cup of coffee while they’re in there,” Ritzman says. “I don’t know what it is about flowers and bakeries.”

Ritzman sees symbiotic relationships everywhere, especially in her second profession. Her pesticide-free flowers attract pollinators — birds, bees, butterflies and the like — which benefit the family farms that surround her. She stands in her driveway and points in three directions.

“100-year-old farm, 100-year-old farm, 100-year-old farm,” she says.

Her farmer-neighbors haven’t necessarily grown the same crops for a century. One neighbor has swapped tobacco for hemp. The point is, Ritzman sees herself as a part of the region’s agricultural tradition.

It just so happens that her boutique farm covers half an acre and that she’s wearing Ray-Ban sunglasses, a yoga studio T-shirt and cropped joggers with a snakeskin print.

“Can you tell I’m an old soul?” she asks.

She means it.

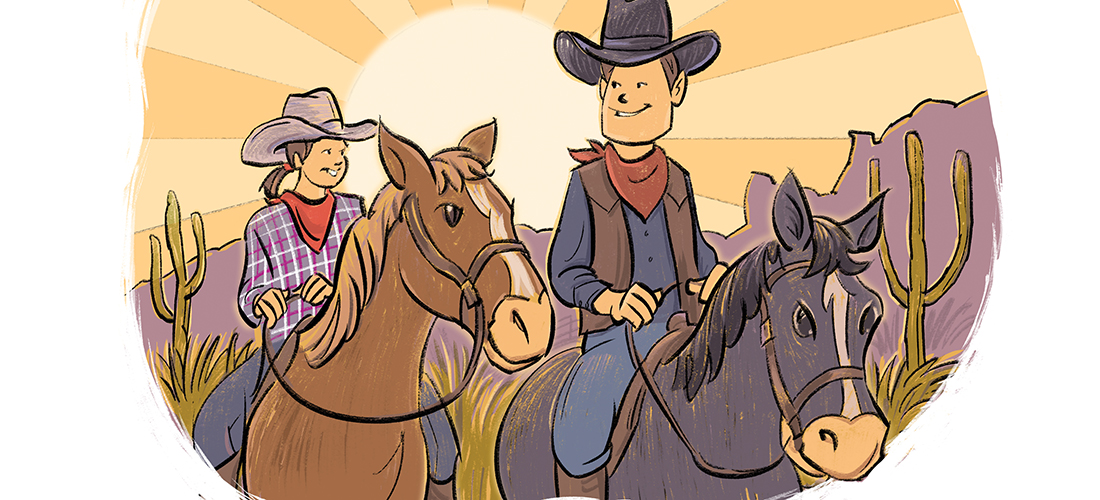

Ever since she was a girl in Amarillo, Texas — back when her mom played “tea party” with her and served graham crackers with chocolate frosting — her goal was to own a tearoom.

Then came life.

And two sons.

And the need to work as a single mom.

Ritzman typed. She took shorthand at 110 words a minute — almost as fast as most people talk.

Her fingers flew over a 10-key calculator.

“I learned real quick to say, ‘I’m finished. Is there anything else to do?’ I had a good work ethic, I guess,” she says.

She mastered bookkeeping, then spreadsheets. She transplanted her family and worked for various bosses — and their wives.

“When they said, ‘Oh, Shellie, can you design a garden club invitation?’ my little artsy self was on it,” she says.

She came by her little artsy self honestly. Her father had been a Marine, then an overall-wearing gas refinery worker, then, in a somewhat surprising turn, a self-employed commercial artist who took a mail-order course to learn to draw for profit.

He set up his own shop and designed business cards, letterhead and logos.

He painted watercolors.

He designed a commemorative coin celebrating Evel Knievel’s motorcycle jump over the Snake River at Twin Falls, Idaho, in 1974.

“The Texas Cattlemen’s Association still uses my dad’s logo,” Ritzman says.

She fed her own simmering talent with nature.

In her time off, she tended flowers in her yard — veggies never held much appeal for her — and read Victoria magazine, losing herself in slick pages filled with bowers of blossoms, smartly set garden tables and handicrafts fashioned by clever women.

Sound familiar?

When her sons graduated from college, and her boss sold his family’s Winston-Salem company, Ritzman saw blocks of time open up before her.

She bought a book called Floret Farm’s Cut Flower Garden: Grow, Harvest and Arrange Stunning Seasonal Blooms.

She followed up by taking Floret’s six-week class online.

“Their concept is, you can grow a lot of flowers in a small space,” she says.

She had the space, reclaimed from her boys’ soccer balls and go-carts.

She had the smarts.

She had the shovels.

She dug in. With the help of her second husband, Nevin Ritzman, a retired firefighter, she plopped raised beds made of corrugated metal atop islands of cypress mulch and started planting in 2018.

She made a lot of mistakes.

She buried bulbs, plugs and seeds at the wrong time of year.

She covered the beds with cloth that was too thin and shredded easily when it was removed and replaced for frost.

She misfired with flora that frowned on the climate along Cherry Vale Drive.

She tinkered until she found what worked best.

Peonies

Sweet William

Tulips

Mums

Gladiolas

Dahlias

Zinnias

Snapdragons

Sunflowers

Yarrow

and more . . .

When she hit a snag, she got advice from a supportive online community.

“I follow probably 2,000 flower farmers,” she says. “It’s not a competitive community. It’s a collective community.”

She saved what she learned in her own databases.

“People say, ‘How do you manage it?’ I say, ‘It’s a skill set: Spreadsheets out the wazoo.’ ”

In 2020, she started delivering her prepaid subscription bouquets, the only business model that made sense to her.

“I’m not go gonna sit at a farmers’ market somewhere, and nobody buys my flowers, and then I take them home, and they die,” she says.

She opened her yard for the first class later the same year. COVID delayed the startup. People still came. Some wore masks, some didn’t. Ritzman left it up to them.

Most customers felt safer knowing that the classroom was an outdoor room, essentially a covered patio anchored by a fireplace, stirred by a ceiling fan, and decorated with hanging light balls.

Last year, the Ritzmans bought a slice of land next to their yard. They colonized it with more raised beds and a heated and cooled workshop that seats 12 people — the max for events— in all kinds of weather.

Calling it a workshop is an understatement.

“I thought, ‘OK, people are going to be dining out here. It needs to be froufrou,’” she says.

Mission accomplished. Smelling of paint and sawn lumber, swaddled in creamy fabrics, and floored with gray vinyl planks, the 14-by-28-foot space (which inspired the vision described at the beginning of this story) features a long, custom-built, bar-height table centered under an elegant light fixture.

A wallpaper mural, reminiscent of a Dutch still-life painting, reminds viewers that “In Joy or Sadness, Flowers Are Our Constant Friends.”

Apothecary jars parade dried petals of marigolds, peonies, roses and lavender.

Event participants can buy floral bookmarks, candles and other what-nots.

Ritzman will use the workshop for classes, bouquet assembly and private events, should someone want to rent it.

Her Victorian-style greenhouse also is available.

“You know the custom Boho picnic people?” she says. “If they want to offer somewhere to do a picnic, here it is.”

The same offer applies to the green outbuilding she calls the flower shed, which she uses chiefly as a photo studio for her wares.

“If someone calls and says, ‘Hey, can I have an intimate dinner out there with my girlfriend?’ sure, we’ll fix you up.”

Already, she makes the colorful grounds available, by the hour, for photography and video sessions.

Most visitors, though, come for the classes.

“Once they get here, they’re like, ‘OK, I get it. It’s a place to come play with flowers,’” Ritzman, 62, says.

Her customers are overwhelmingly women.

“You’ll have the sassy girls, all dressed up with their girlfriend groups. We had a group of homeschooled girls. We get a lot of sister groups, a lot of mother-daughter groups,” she says.

Recently, the first male student signed up to take a two-hour charcuterie class with his wife.

“I told my husband, ‘You have to be here so he won’t be intimidated,’” she says.

Regardless of gender, Ritzman believes, her customers are hungry for beauty and company. As the pandemic wanes, they’re emerging like the lime green knuckles of seedlings, testing the environment to see if it’s safe to bloom.

“Last year, we did really well, but this year we’re selling out quicker,” she says. “People are ready to get out.” OH

Learn more about Ritzman’s business at her website, mygardenblooms.net or on her Instagram page, @mygardenblooms.

Maria Johnson is a contributing editor of O.Henry. She can be reached at ohenrymaria@gmail.com.