The extraordinary life of WWII flying ace George E. Preddy Jr.

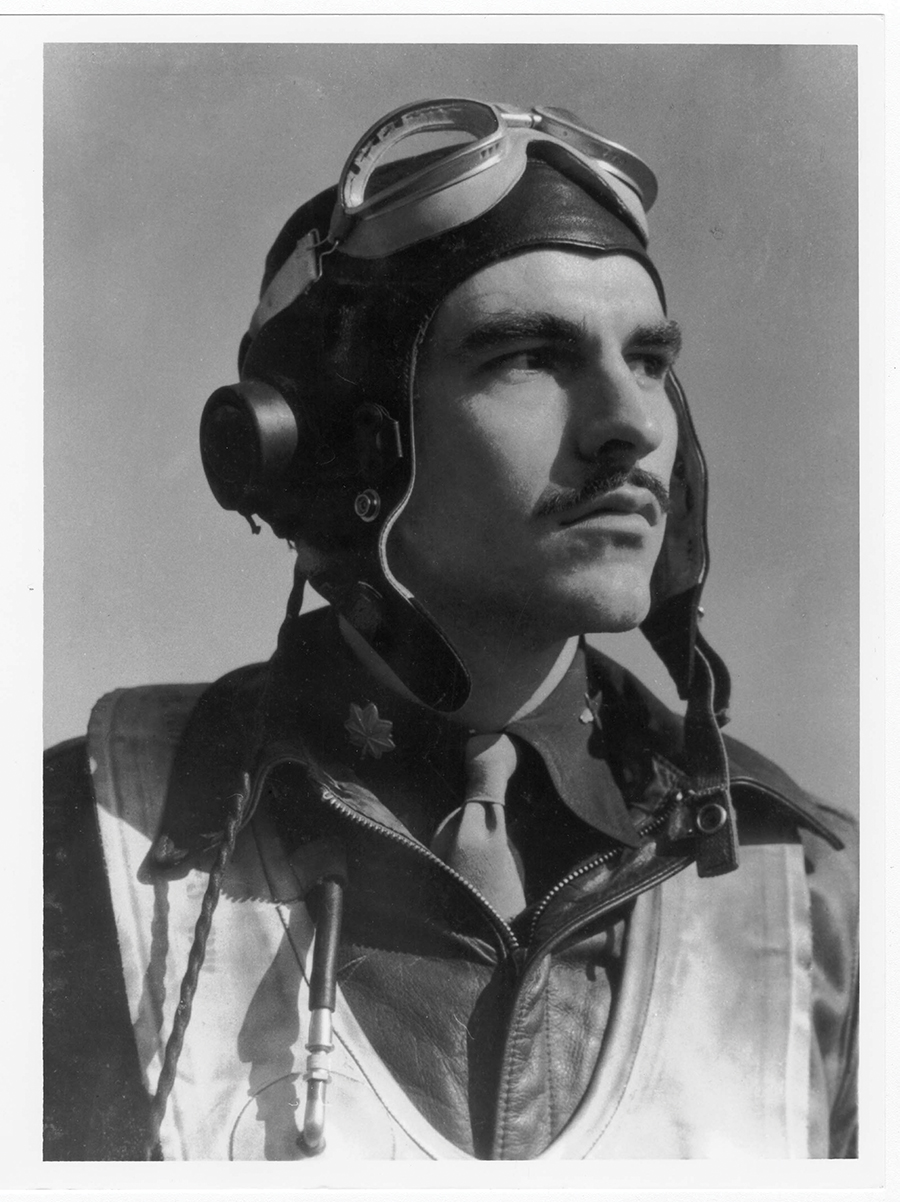

By Ross Howell Jr.

Let’s start with darkness. Then we’ll look for light.

On Christmas Day, 1944 — 75 years ago — our city’s most famous aviator, George Earl Preddy Jr., was killed. He was 25 years old. Just months later, on April 17, 1945, his baby brother, William Rhodes Preddy, was also killed. Bill was 20.

The two men rest side-by-side — not in Greensboro, where they attended Sunday services as boys at West Market Street United Methodist Church, but in Lorraine American Military Cemetery, Saint-Avold, France.

Both men piloted the P-51 Mustang, perhaps the most famous U.S. fighter of World War II. George was flying in support of the Battle of the Bulge, an enormous German counterattack launched in Belgium after the Allied invasion at Normandy on D-Day. Bill was strafing an enemy airfield near Prague, Czechoslovakia (now the Czech Republic), just days before V-E Day, when Germany unconditionally surrendered to the Allies.

George and Bill grew up in a modest, brown-shingled house their father, George Earl Sr. (whom the family called Earl), had built in 1921 at 605 Park Avenue in Aycock (now Dunleath). The household included their mother, Clara Noah Preddy, and sisters, Jonnice (oldest child) and Rachel (born between the boys).

George was small — he stood 5 feet 9 inches tall and weighed 125 pounds as a grown man. And he had big ears. The neighborhood boys nicknamed him “Mouse,” a moniker that stuck till his WWII days, when he was renamed “Ratsy.”

Since the Preddy house was near War Memorial Stadium, George frequently played on the tennis courts there. He was tremendously competitive, and enterprising enough to make money on a soft drink concession he dubbed, “The Mouse Hole.”

George attended Aycock School (now Melvin C. Swann Jr. Middle School) and Greensboro High School (now Grimsley High School). Not big enough to make the high school basketball team, he played hoops at the YMCA, set up a horizontal bar in his backyard to practice gymnastics, and even tried to bulk up his muscles with the popular Charles Atlas bodybuilding method.

He was a serious enough student to double up on courses, graduating from GHS at age 16. While he’s remembered as being cerebral and quiet, he could cut up with the best of them, once convincing his buddies to dangle him by the ankles from a second-story school window in order to prank a teacher on the floor below.

Following graduation, he worked at a cotton mill and attended Guilford College for two years. Then came the experience of a lifetime.

On November 13, 1938, George wrote in his diary: “Had my first real airplane ride today. Hal Foster took me to Danville with him in his little ’33 Aeronca. It took us 30 minutes to make the trip. I see now how great the airplane is. That trip was the most wonderful experience I ever had. I must become an aviator.”

Just months later, after learning his flying skills from Bill Teague, an A&P grocery store manager, George soloed from a grass airfield near Vandalia, six miles south of Greensboro, in Teague’s Waco biplane — named Wanda C, after Bill’s wife.

Teague and George hit it off. After George’s solo, Teague suggested that they each chip in $75 to buy a second Waco. Together, they’d set out barnstorming.

“George was absolutely crazy about an airplane,” his father Earl said in a 1966 interview recorded by then-director of the Greensboro Historical Museum, Bill Moore. “He wanted to fly all the time.” With “headquarters” at a grass airstrip just outside Vandalia, George and Teague would fly to Liberty on Sundays and take passengers up in the plane for “hops.”

“They had this little two-seater,” Earl continued. “I believe they charged a dollar for a five-minute ride.” Earl, who was employed by the railroad “for 49 years and 7 months,” usually worked a freight run to Sanford on Sundays. The tracks ran right alongside the airfield near Liberty.

“I noticed a little gum tree there,” Earl said. “And if George wasn’t up in the air, he’d be standing under that tree in the shade and wave at me. I named the tree, ‘George’s tree.’”

While barnstorming with Teague in 1939, George’s cowling flew up in front of the cockpit, completely blocking his view. Looking from the side of the aircraft, he was able to land in a cornfield with no damage. The cowling latches had not been properly fastened, and the incident underscored for him the importance of a pilot’s thorough walk-around of an aircraft before flight, a lesson that would remain with him through his military service.

On September 1, 1939, Adolph Hitler’s armies raged into Poland, employing a furious tactic called blitzkrieg — “lightning war.”

That fall George boarded a train bound for Pensacola, Florida, and the Naval Air Training Center. He passed all application tests except the physical — the Navy said he had high blood pressure and curvature of the spine.

Back home he did stretching exercises to improve his back. After applying twice more and being rejected, he decided to spend another summer barnstorming with Teague.

The first performance of the 1940 season was at Walnut Cove. With few customers at the airfield, they made three low passes over Main Street and turned out a real crowd.

George and Teague were vagabonds with wings, flying from town to town, sleeping under their aircraft, staying at a YMCA every third night so they could get a shower.

Adventures followed.

There was the time George noticed a police car’s flashing lights out on the field as he landed near Valle Crucis. The officers were carrying the state representative for the district who wanted to get to Asheville in a hurry, rather than take the slow way on curvy mountain roads. George obliged, and was paid handsomely.

And there was the time a mother asked him to fly her 10-year-old daughter to Winston-Salem because the medical help the girl needed wasn’t available in nearby Mount Airy. He refused payment of any kind. At the end of the barnstorming season, he received a letter from the mother, telling him her daughter had successfully recovered from pneumonia.

News of the war in Europe grew more ominous by the day. Holland, Belgium and France were under Nazi control, and the aerial Battle of Britain had begun.

George gave up on the Navy and applied to the U.S. Army Air Corps. He was accepted, and his name added to a long list for cadet class. Then, on September 7, Hermann Goering ordered his Luftwaffe to launch the London Blitz, an all-out bombing campaign to destroy the city. Streams of German aircraft flew missions by day and by night, wreaking havoc below.

Anxious to get in on the fighting, George enlisted with the National Guard at the advice of recruiters. He did his basic training in Fort Moultrie, South Carolina, then was sent to Fort Screven, Georgia. Next he was ordered to Darr Aero Tech, a flying school southwest of Albany, Georgia. By October 1941 he had reported for advanced flying school at Craig Field, Alabama.

The clouds of war were rapidly darkening.

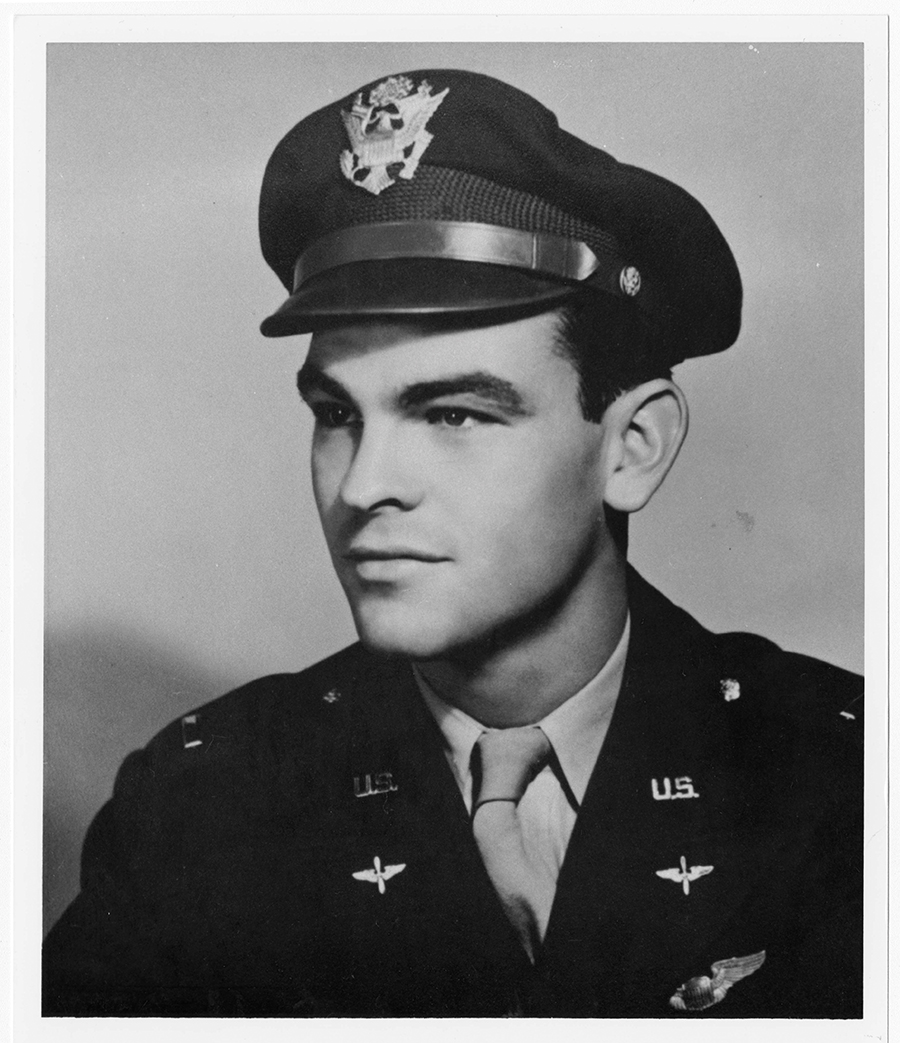

On December 7, the Imperial Japanese Navy struck Pearl Harbor. Five days later, George graduated with his class from flying school at Craig Field. His mother, Clara, rode the train to Alabama and proudly pinned pilot’s wings on her son’s blouse at the ceremony.

Commissioned as second lieutenant, George used a short leave to come home to Greensboro before reporting to West Palm Beach, Florida, to join the 49th Pursuit Group, 9th Pursuit Squadron. Once he checked out in the P-39 Airacobra fighter, he was ordered to ship by train to San Francisco, where he boarded the U.S. Army Transport Mariposa on January 11, 1942, destination unknown.

In February the transport docked near Melbourne, Australia. George’s unit was moved by train from Melbourne to Sydney. It had been six weeks since he’d flown an airplane.

He received scant training in his new aircraft, the P-40 Kittyhawk. George’s unit ferried their fighters north to Brisbane, then set off northwest to a primitive base near Darwin, where he slept on the wing of his aircraft. He was now in a battle zone.

In honor of the Old North State, George dubbed his P-40 Tarheel.

Soon his unit was scrambling to intercept Japanese bombers and fighters. But George was still new to the game. On March 30, 1942, he wrote in his diary: “I had a perfect shot at a Zero [Japanese fighter], but missed by not turning one gun switch on.”

By April, George could lay claim to having damaged two enemy aircraft but still had recorded no aerial victories. Then in July, he nearly lost his life.

On an evening training mission with three other pilots, George and a wingman were flying level, simulating enemy bombers, while two other pilots “bounced” them from above, diving from an altitude of 20,000 feet. On one pass a pilot misjudged and crashed into George’s plane just behind the cockpit.

The first pilot was killed instantly. Badly injured, George was able to bail out before his airplane went down. A tree limb pierced his leg as he parachuted into heavy brush. Fortunately, he was rescued — bleeding badly, but still conscious — before night set in.

What followed was a long, painful transfer by air to the new U.S. Army hospital in Melbourne. He would spend weeks bedridden — and three months in recovery.

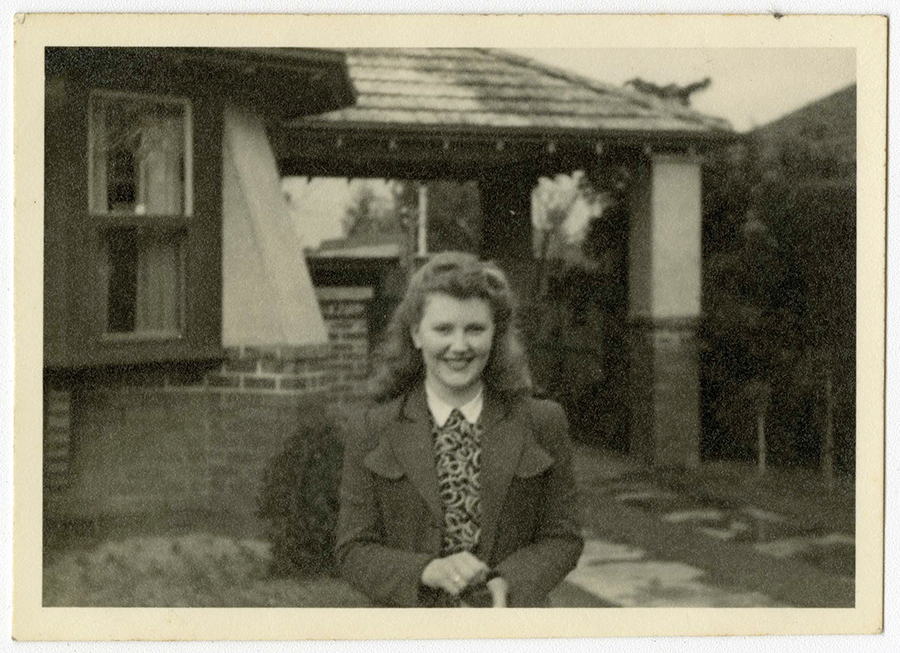

But fortune smiled. A young Australian woman named Joan Jackson often visited soldiers at the hospital to cheer them up. Joan made quite an impression on George. When he was finally up on crutches, he’d go on outings with her. Although he saw other women at the time, it seemed that he was smitten.

On September 9, 1942, George wrote in his diary: “Had dinner at Joan’s house this evening. . . . Her Dad is a famous golfer and a very nice fellow. Also her sister is a clever girl and very attractive. I think I could love Joan.”

There’s a portrait photograph of Joan wearing George’s wings. But the record about her goes silent for a while.

At the end of September, George was ready to report back to Darwin. He made it as far as Brisbane, where he received two sets of orders: one directing him to return to the States, and the other promoting him to first lieutenant.

By way of Fiji, New Caledonia, Canton Island, Honolulu, California, by military transport to Salt Lake City, and then by rail, George journeyed home to North Carolina. He was surprised and happy to see his father Earl board his train in Reidsville. Together, father and son rode south to Greensboro.

George’s nine-day leave was a whirlwind of family and friends. His brother Bill and childhood chum “Bozo” Boaz drove him to Winston-Salem to see Bill and Wanda Teague. During the visit, his old instructor and barnstorming pal flew Bill, Bozo, and George to Charlotte and back in his new Stinson Reliant.

On November 10, George boarded a train for Oakland, California. He had been a combat pilot for nearly two years, and had yet to score an aerial victory.

In Oakland he was introduced to the P-38 Lightning, an elegantly designed, twin-engine fighter. November 19 he wrote in his diary: “Spent the day at the field and checked out in the P-38. Flew it 45 minutes of the most enjoyable flying I ever did. That is a wonderful flying ship and fast as its name. . . .”

Next stops: Orlando, Florida, then back to California, then First Fighter Command in New York. He wrote in his diary on December 31: “Well, here it is the last day of 1942. . . . I am on a train setting out on my sixth crossing of the country since this time a year ago. . . Hope by the end of next year I can have done much more for my country than I have last year.”

From New York George was assigned to the 320th Squadron at Westover Field, Massachusetts, where he checked out in the P-47 Thunderbolt, a thick-fuselage, powerful fighter nicknamed the “Jug.” In January he was transferred to the 34th Squadron of the 352nd Fighter Group in New Haven, Connecticut, a tactical unit training to go overseas.

George was finally preparing to enter battle in one of the most dangerous places on earth — the skies over Europe.

On June 30, George boarded the Queen Elizabeth, bound for England. He had been promoted to captain. Six days later he disembarked at the Firth of Clyde, taking a train to a deserted Royal Air Force airfield in Bodney, 90 miles north of London.

At Bodney George named his P-47, Cripes A’Mighty, a phrase he used for luck when shooting craps. On December 1, he scored his first aerial victory — a German Me 109.

George’s P-47 was hit by enemy antiaircraft fire in January 1944. He was forced to ditch in the icy waters of the English Channel. With rough seas and poor visibility, the amphibious aircraft sent to rescue him ran over him three times before they could fish him out.

“They damn near killed me!” he complained.

Piloting his replacement P-47, Cripes A’Mighty 2nd, George continued to pursue enemy aircraft, both on the ground and in the air. On March 22, 1944, he was promoted to major and named operations officer of the 487th Fighter Squadron. December 22, he achieved a second aerial victory, shooting down a Me 210.

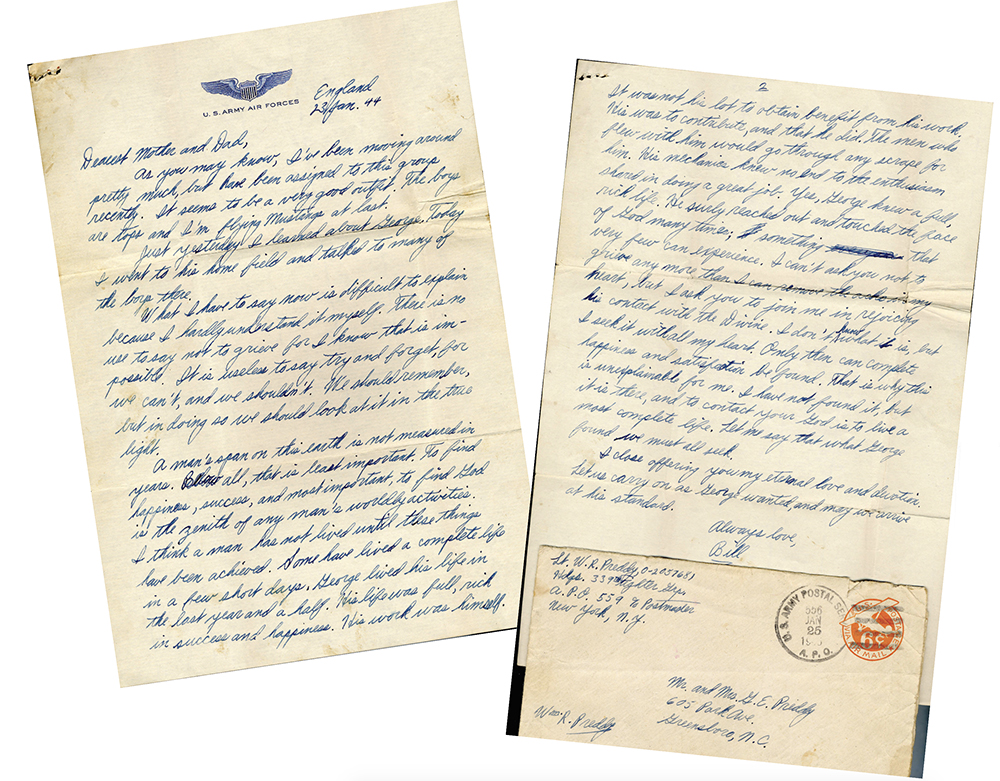

By letter he learned that his brother Bill was making good progress in his military training back in the States.

“You should take advantage of all the instrument time you can get,” George wrote Bill on April 17, “because when you get to our theater of operations you will fly in weather you wouldn’t walk outdoors in at home. . . .”

That same month, George’s outfit, the 352nd Fighter Group, transitioned from the P-47 to the P-51 Mustang. George named his new airplane Cripes A’Mighty 3rd. A nimble, fast fighter, the P-51 with drop tanks had the range to escort U.S. heavy bombers on raids deep into Germany, protecting them from enemy fighters.

Flying just such a mission on August 6, 1944, George became a legend.

For two weeks his squadron had seen fierce action, and he personally had accounted for more than six enemy aircraft destroyed. But poor weather was predicted for August 6, so no mission was planned.

George celebrated at the craps table in the officers’ club. Exclaiming “Cripes a’mighty!” with each roll of the dice, he won an astounding $1,200.

Ever the dutiful son, he used his winnings to purchase a war bond and mailed it home to Clara. Greater merriment ensued.

But a mission was called the next morning, and it was George’s turn to lead. Others offered to fill in, but he insisted, still tipsy enough to fall off the table he was standing on to brief the men. Their mission was to escort U.S. bombers to a target east of Berlin.

Breathing pure oxygen got George on the mend, but when he buckled into the cockpit of his P-51, he had a brutal hangover.

That day he shot down six enemy aircraft.

It was a feat unprecedented in the course of the air war in Europe, and though his exploit later was equaled, it was never surpassed.

Photographers, reporters, and correspondents arrived at Bodney to get George’s story.

Three days later, he was interviewed about his exploit for a CBS radio broadcast. The program announcer was the famed head of the CBS European Bureau, Greensboro’s Edward R. Murrow.

As was his wont, George closed the session by acknowledging others: “You just can’t watch your tail and concentrate on your shooting, too. That’s why my wingmen are due as much credit as I am.”

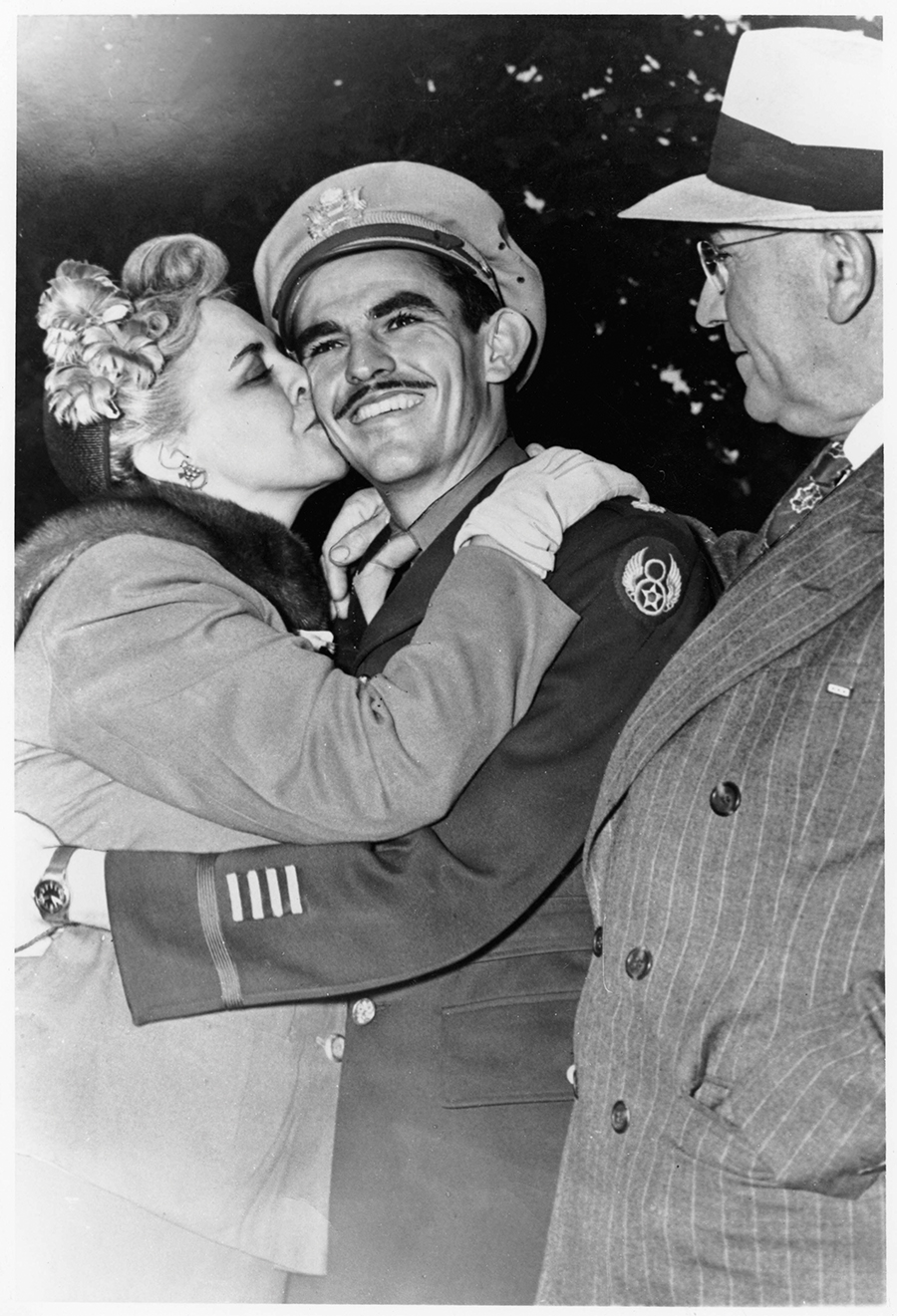

In September George was granted a 30-day leave. It was a glorious homecoming. Clara and Earl met him in Washington, D.C., where he was scheduled for a couple days of publicity interviews, standard fare for an American ace.

Then it was on to Greensboro. George addressed a crowd at a ceremony in War Memorial Stadium, just blocks from where he’d once sold soft drinks from “the Mouse Hole.” He gave speeches to the Boy Scouts, to high school students, to the Chamber of Commerce.

And George announced his engagement to Joan Jackson, the Australian he’d continued to romance by mail. They planned to wed at war’s end.

George then traveled with his family to visit Bill in Venice, Florida, where his brother was in the final phases of air combat training. The two even engaged in a mock dogfight in P-40s, with Bill giving George as good as he got.

“Don’t get cocky!” George told his little brother.

Back in Greensboro, he agreed to do a local broadcast radio address. When he was introduced and asked to tell the audience about himself, he spoke instead about Edward R. Murrow.

George spoke about how he and the other officers gathered in the lounge of the Queen Elizabeth — the troop vessel that first carried him to England — listening on the radio to Murrow’s 15-minute news broadcasts, “when he gave the straight dope on the war news of the day.” He spoke about how kind Murrow was to him when he was interviewed for CBS, how they talked about the people they knew back home in Greensboro.

“Ed Murrow knows what he speaks about because he has spent every available moment getting a better insight into the feelings of the war-stricken peoples of Europe,” he said. “Greensboro should be proud of him.”

By the end of September, George was anxious to get back in the fight. His father Earl tried to convince him to stay stateside, since he had flown many more combat missions than were required.

But George was adamant about returning. He felt he had a job to do.

When he returned to the 352nd Fighter Group at Bodney, George was assigned to lead the 328th Fighter Squadron, the group’s goat, with the lowest number of enemy aircraft destroyed. His commanding officer felt that with his leadership and reputation, George could get the squadron on track.

He took over on October 28, 1944, christening his new P-51 simply, Cripes A’Mighty, no number.

George took up where he had left off, destroying enemy aircraft as squadron leader. The overall aggressiveness and effectiveness of his squadron considerably improved.

That fall, Giles “Runt” Teague, Bill Teague’s younger brother, paid George a visit. Runt asked if George could help him transfer from piloting heavy bombers to fighters. George agreed to have his commanding officer write a letter requesting the transfer.

On December 10, 1944, George answered a letter from the Teagues, thanking Wanda for the fruitcake she had sent him. “I have some fine pilots and am proud of the job they are doing,” he added, “particularly on one mission, when we knocked down 24 Jerries to set a new record.”

A week later he posted his final letter home to his parents. He complained about the slow mail service, described the awful weather in London, where he’d been on a 48-hour pass.

“I sure hope Uncle Laurie [his mother Clara’s brother, who’d been badly injured in a rail accident] is better now,” he wrote. “Mail [delivery] from Joan [his fiancée in Australia] is even worse than from you. I don’t expect to hear from her until way after the first of the year. . . Best love always, George.”

In horrendous weather conditions the morning of December 23, Preddy flew with his squadron to Y-29, a primitive air base near Asch, Belgium. Their job was to provide air support for the Battle of the Bulge.

On Christmas Day, George briefed his squadron on their mission, hiked up a pants leg to show the men his bright red “fighting socks,” and said, “Let’s go get ’em!”

And that was it.

After the fighters in his squadron became scattered in a dogfight, George spotted an FW 190 flying at treetop level, and dropped to the deck to pursue the German plane. Cripes A’Mighty was brought down by friendly antiaircraft fire.

Runt Teague’s transfer never came through. He was killed when the B-17 Flying Fortress he was piloting went down over the English Channel on December 30, 1944.

Bill Preddy was killed four months later when his P-51 was destroyed by enemy antiaircraft fire as he and a wingman strafed a flak tower in Czechoslovakia.

George died as the highest-scoring Mustang ace of World War II.

Joseph J. “Red” McVay, the assistant crew chief for whom George always had nothing but praise, commented about his death in a letter to the Greensboro Daily News.

McVay explained that a keg of beer had been purchased to help the enlisted men celebrate the holiday, but when word “came that the Major, our Major, had been killed . . . we emptied our glasses on the ground.

“Christmas will never be the same for me again,” McVay concluded.

Earl Preddy in an interview described George as “just an ordinary American boy.” He described his son Bill the same way. Certainly Earl and Clara’s boys were like many of their buddies. But their love of flying, their love of country, their skill, their determination and the dark realities of war made them heroes.

Their lights burned brief and bright, much like the star that guided searchers to a stable in Bethlehem so long ago. Surely the firmament holds stars for the brothers, and for all their like.

Merry Christmas. OH

To learn more about the Preddys, Ross Howell Jr. recommends Wings God Gave My Soul — the Factual Story of One of America’s Greatest Fighter Pilots of World War II, George E. Preddy Jr. by Joseph W. Noah (1974), George Preddy: Top Mustang Ace, by Joe Noah and Samuel L. Sox Jr. (1991), Carolina Ace, a documentary film, by Shawn Lovette, and the Preddy Memorial Foundation, preddy-foundation.org, and the Preddy exhibit at Piedmont Triad International Airport.

Photographs courtesy of Greensboro History Museum