Chief

And the art of moving on

By Nancy Oakley

“That was our hand-washing station,” he says, pointing to a snapshot of an orange Igloo cooler. The photograph is neatly laid out in a column among four others in a narrow album.

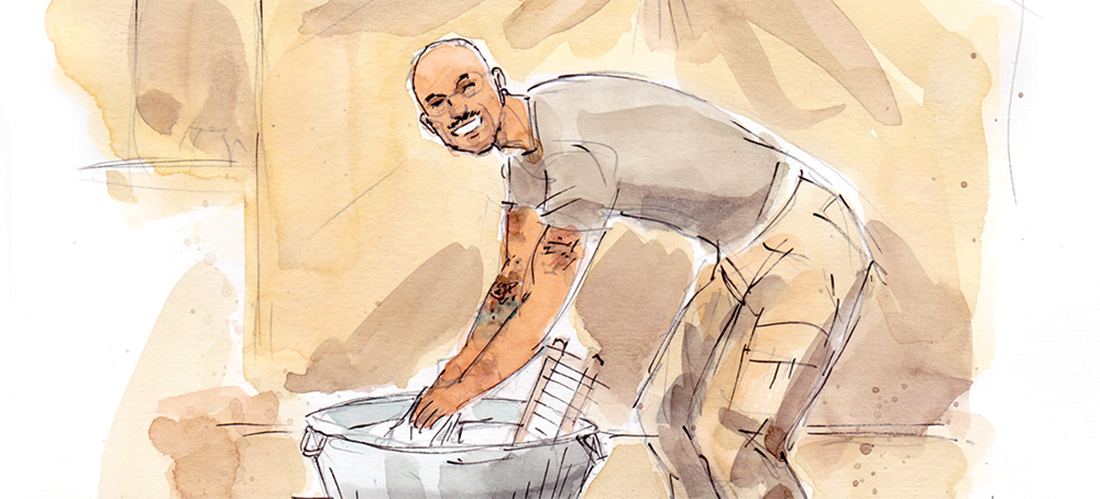

“There’s me, washing my clothes,” he explains as he turns the album’s pages. He looked as he does now, with the same buzz cut, squinting through wire-rim glasses, his toothy grin flashing beneath a woolly worm of a mustache. In the photo, he wore a tan T-shirt and fatigues, his booted feet planted firmly on the ground as he squatted before a bucket containing a shirt immersed in soapy water.

“We’d hang it up and it’d dry in the sun just like that,” he recalls, snapping his fingers. “Boy, it was hot, too. Not as hot as the Mojave when I was in training, though. That was brutal.” He pronounces it: MOH-JAVE, with a hard “j” and a long “a” and equal emphasis on both syllables.

Chief, as my friends and I call him, continues flipping through the photo album following his favorite dinner of grilled chicken and chops. He shows us the tent where he and his company lived, a large, white structure distinctive only because of the bland and barren landscape surrounding it — sand — and the narrow cot with his duffle lying next to it.

“There’s Fallujah,” he continues, “some Iraqi kids.” The photo reveals a depressing alley flanked by gray buildings, the latter, extreme close-ups of wide-eyed children mugging for the camera.

“And that’s mail. See? All those orange bags? Look at that!” Here Chief’s tone becomes more animated, as if he were reliving the thrill of receiving news from home.

Back in the day, home for Chief was one of the aging apartments in a leafy neighborhood we all lived in when we were young and poor. His was the smallest, because it was the cheapest — an ideal arrangement for a student who had lived for four years in a cramped submarine. As a new recruit, he had sometimes been relegated to sleeping in the tiny compartment over the nuclear missiles.

He’d wanted to be a Marine, but for whatever reason wound up in the Navy.

“When the guy at the recruiting office said, ‘How about submarines?’ I said, ‘Yeah, that sounds OK.’” Chief remembers. “And the first thing I thought when I got there was, ‘How do I get out of this?’” He laughs about it now. But at the time he had no other options, the laughing, skinny kid in another photograph from an even more distant era. The kid with a mop of hair, sporting cutoff jeans, whose stepmother showed him the door after his father died.

Chief moved from subs to helicopters. Reconnaissance. “I saw other guys doing that, and I said, ‘Hey, I want to do what they’re doing,’” Chief once explained. “That’s how you learn things. Move on.”

By the time we knew him, Chief was the odd man out, a bit older than the rest of us, with his trademark buzz cut, military posture and short fuse, not to mention his unabashed patriotism. A bumper sticker on his SUV read “Semper Fi,” an homage to his dream deferred — though he did join the Naval Reserves attached to a Marine unit. Then there was the vanity plate, “WETHEPPL,” which drew smirks among the hipper-than-thou set.

But Chief had a great sense of fun. He’d take one couple’s child for walks in her stroller, play fetch with their dog. His favorite movie was A Few Good Men, and Chief loved to quote the courtroom dialogue verbatim, ending in crescendo with its now famous line,

“You can’t handle the truth!”

Then he’d laugh and take a sip of Michelob, and replay the scene and quote the lines all over again.

On another occasion Chief had gone to a formal dance, wearing his dress whites. He came back, his date on his arm, and knocked on all our doors, pretending to have been stabbed, spilling fake blood on the sidewalk, before doubling over with laughter.

His date that night ended up becoming the mother to his only son, but Chief’s relationship with her soured, becoming fraught with custody battles. He moved in and out jobs but continued his Reserve duty, and long after he’d left our little enclave, he would return for dinners of chicken and chops, and screenings of A Few Good Men.

In 2003 when Reservists were called up, Chief left for his first tour, attached to a medical unit. One of us took care of the golden retriever he’d acquired. Even the ex-girlfriend cried and wrote letters — while demanding child support for their infant son.

We were relieved when Chief came home in one piece. Then he signed up for another tour. And another. And another. He rarely spoke of them.

After the last tour, he resumed his pattern of moving from job to job and tried to re-enlist — only to be rejected at his advancing age. He gave up a job at one of the hospitals to work at the V.A., in spite of the long commute it required.

Chief’s been at that job for a while, and he’s mellowed, preferring college football games on TV to A Few Good Men. He speaks proudly of his son, now 18.

“A neighbor of mine — I guess he’s about 70 — asked me if I wanted him to enlist,” he tells us after he’s closed the photo album. “I told him that was my boy’s choice. It kind of shocked him.” Chief pauses to take a sip of iced tea, having switched from Michelob for the evening.

We all stifle yawns and start to break up the evening, with “g’nights,” and hugs. Chief walks down the driveway to the modest sedan he now drives. He gets in and starts the ignition, waving through the window and flashing his toothy grin. As the car fades away into the darkness, the only thing visible between its taillights is the vanity plate: IRAQX4. OH

Nancy Oakley is the senior editor of O.Henry.