Simple Life

“The Cocktail Cat”

The spirit of a roaming feline

By Jim Dodson

I have a friend who never fails to show up at cocktail time.

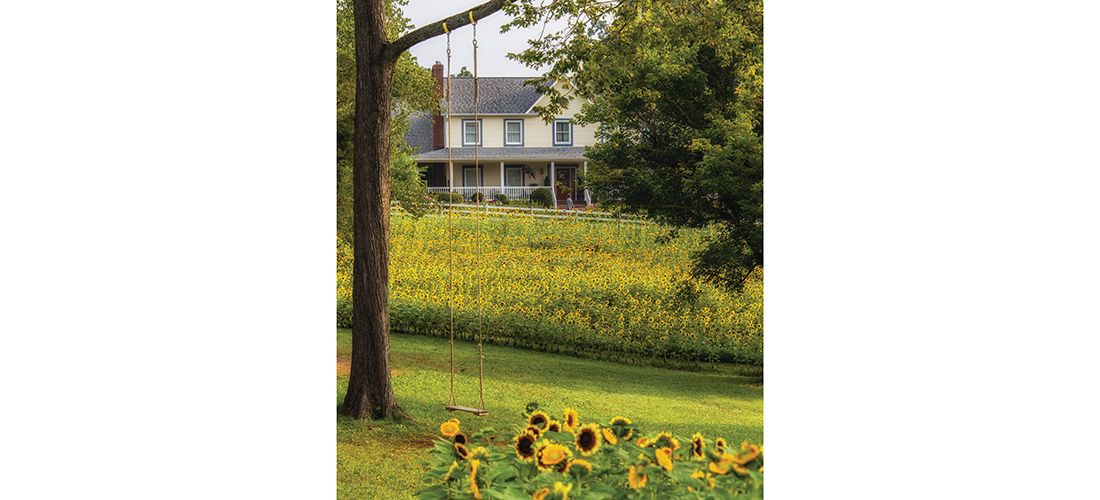

Wherever he’s been, whatever he’s been up to all day, he appears like clockwork as I settle into my favorite Adirondack chair under the trees to enjoy a sip of fine bourbon and observe the passing scenes of evening life.

Fortunately, he doesn’t drink bourbon. He doesn’t do much of anything, near as I can tell, except annoy the dogs and pester me well before dawn for his breakfast after a night out carousing the neighborhood, before snoozing all day on the sunny guest room bed like a house guest who won’t leave.

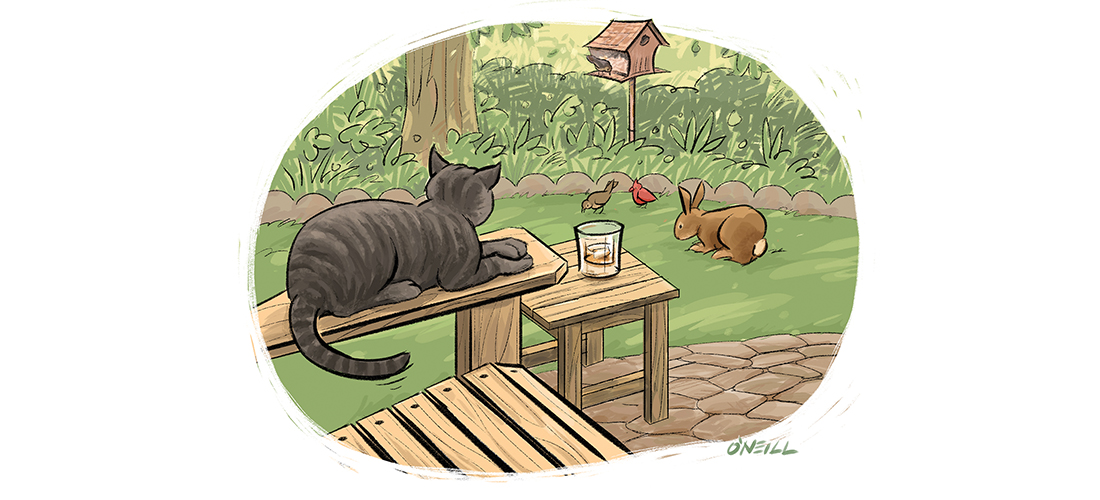

We call him Boo Radley after the peculiar character who saves Scout Finch in To Kill a Mockingbird. Our Boo, an old, gray tomcat who would rather watch birds than chase them, hasn’t caught a bird of any sort in years.

At cocktail hour, rain or shine, you can set your watch by Boo’s punctuality. Hopping up on the arm of my chair or the small table where I set my whiskey while I reflect on the day’s events and find pleasure in watching birds at the feeders, Boo is either too fat or too old to bother trying to catch them. Even in his salad days he was never much of a killer, though he would leave the occasional mouse on a discreet lower step of our back porch.

Like his cinematic namesake, Boo’s an oddly friendly fellow once he gets to know you, though he generally doesn’t cotton quickly to strangers. Curiously, we’re half convinced several folks in the neighborhood are secretly feeding him, because he’s beginning to resemble a bowling pin. Perhaps he has them fooled into believing that he’s actually homeless. Nothing is further from the truth. He’s managed to ditch every expensive collar and bell we’ve put on him over the past 10 years in order to keep his dining ruse going.

In fact, Boo Radley has had at least three very nice homes. The first was in Southern Pines when No. 2 son brought him home on a cold winter evening. He was just a small gray foundling you could hold in the palm of your hand, a friendly little cuss who appeared half-starved and very grateful.

Second Son named him “Nikko,” which means “daylight” in Japanese, and planned to take him off to Boston, where his new job in the hospitality industry awaited. His mom wisely interceded, pointing out that the last place a homeless kitten needed to live was with a single career guy working long and impossible hours.

So we inherited Nikko. The first thing I did was give him a new name and identity.

He seemed to like the name Boo Radley, though who can ever say what a cat is really thinking.

I suppose that’s part of that peculiar feline charm. Dogs occupy space, someone said. Cats occupy time. They act like you’re on this planet to serve them and should be damn grateful to do so. Another friend who has several cats informs me that cats know the secret of the universe. They just won’t tell anybody.

During our many years in Maine, we had a succession of barn cats who wormed their way into our affections. As a lifelong dog lover who occupies more space than time, even I came to admire their independence and pluck, somehow surviving the fierce Maine winters and coyotes.

Boo grew up with our three dogs, sometimes sleeping with them, often stealing their food, giving them a passing swat now and then as a friendly reminder of who was really in charge. Bringing up Boo was like raising a problem child.

We eventually moved to a house that had 2 acres of overgrown gardens. Boo didn’t miss a beat. He was always out in the garden, night and day, either following me around or snoozing in the shade on hot summer afternoons. A neighbor warned us there were foxes in the area.

One evening around dusk, I saw Boo sprint across the yard, chased by a young gray fox. Moments later, I saw the young fox run the opposite way, chased by Boo Radley. This game of cat-and-fox tag went on for weeks. Nature will always surprise you.

Not long after that, we moved to the Piedmont city where I grew up and Boo found a new pal in the neighborhood, a large, brown, wild rabbit that comes out every evening around cocktail time to feed on clover and seeds from our busy bird feeders.

I named him “Homer” after the author of the epic Greek poem about a fellow who wanders for 10 years trying to get home. Our Homer seems very much at home in our yard, keeping a burrow beneath my hydrangea hedge.

Boo is highly territorial about our yard — woe to any other cat that sets foot on the property — but has no issue whatsoever about sharing space with a large wild rabbit. I’ve seen the two nose-to-nose many times over the years.

Such are so many sweet mysteries in this world that we cannot explain.

But maybe we don’t always need to. Perhaps it’s enough to simply notice them.

In his splendid essay, “A Philosopher Needs a Cat,” NYU religion professor James Carse writes: “It is not accidental that the word animal comes from the Latin anima, soul. The primitive practice of representing the gods as animals may not be so primitive after all. Soul is not only the small ‘still point of the Tao’ where there is no more separation between ‘this’ and ‘that,’ it is also the presence of the unutterable within.”

A mystic would probably say it’s enough to simply pay attention as different worlds intersect when we least expect it, revealing the presence of the unutterable within.

I have no idea what Boo Radley would say about such matters, being a cat of few — or actually no — words. He’s not one for small talk.

But after so many years and miles together in each other’s company, it’s enough that Cocktail Cat never fails to sit with me as the evening fades, season after season, displaying the kind of timeless nonjudgment and spiritual detachment a Buddhist monk might envy. Boo is perfectly companionable while betraying absolutely no opinion on — or apparent interest in — the trivial matters I present to him as we watch birds feed and I sip my expensive bourbon. At the end of the day, there doesn’t seem to be much separation between his “this” and my “that.”

It also occurs that maybe I have the philosophical proposition plum backwards. Perhaps this aging, well-traveled tom cat simply needs an armchair philosopher to sit with in silence at the end of the day.

Only the Cocktail Cat knows for sure, and he ain’t telling, a perfect presence of the unutterable within. OH

Jim Dodson can be reached at jwdauthor@gmail.com.

.

.