Jewels at The Crown

Do you hear what I hear? A night of live music sure to spellbind

By Billy Eye

Without music, life would be a mistake.

— Friedrich Nietzsche

Hey, I love Christmas as much as the next guy — if the next guy happens to be Santa Claus — but there’s a night I’m just as excited about: an evening featuring a powerhouse lineup of local musicians headlined by Laura Jane Vincent, a modern-day troubadour with a voice like champagne and caviar. It’s happening on December 11 at The Crown, located above the Carolina Theatre. The Crown, by the way, has undergone major renovations, including the conversion of the former projection room — now dressing rooms and a green room — plus new bathrooms and a concession stand.

Laura Jane Vincent is a country girl both at heart and literally, as reflected in her down-home, introspective songwriting.

Laura Jane Vincent is a country girl both at heart and literally, as reflected in her down-home, introspective songwriting.

“I grew up in Raeford, North Carolina, about an hour south,” Vincent says. “I now live in a little town called Glendon, right on the border of Moore County and Chatham County.”

Warbling in high cotton with red-clay-’tween-the-toes lyrics, small wonder her compositions are deeply rooted in Southern musical traditions.

“My stepfather [Al Simmons] taught me a lot of everything I know at a young age,” she says. “He’s a great guitar player. Coming up in that national songwriting tradition, he was very heavily influenced by his best friend, Mike Gaffney.”

Gaffney, BTW, has been a mainstay of the Asheville music scene for around four decades.

“Those two guys exposed me to all sorts of wonderful musicians,” Vincent continues. Among them: Neil Young, Joni Mitchell, Joan Baez, Fiona Apple, Bonnie Raitt and Gillian Welch.

“A lot of female artists,” Vincent says. “That representation was so important to me as a young person. Like, ‘Oh, I could maybe do this myself.’”

Her stepfather also introduced her to open mic nights when she was 15 years old.

“I was a little bit younger than most people,” Vincent remembers of those early days, tagging along behind her musical mentor. “So, I had to kind of — not sneak in or anything — but walk in with authority and act like I belonged there.”

Vincent has been honing her craft at open mic nights in Southern Pines, located near Glendon, and Greensboro, where audiences have witnessed her blossom into a dynamic showstopper at Cup A Joe, Westerwood Tavern and The Green Bean. I first encountered her at the Double Oaks Inn on one of its live music nights, where the finest performers in the area do their thang in a relaxed, living room setting.

Vincent’s transportive, revelatory album, All These Machines, was released in March of 2020, just as everything shut down.

“I’m very, very proud of it,” she admits. “I got to collaborate with my most favorite people.”

The album is imbued with a style harkening back to 1970s singer-songwriters like Janis Ian, Joan Armatrading and Phoebe Snow — but with a Carolina flavor.

While some tunes track solely on Vincent and her guitar, others feature a number of folks she’s performed alongside over the years, well-known locals like Emily Stewart, Pete Pawsey, the ubiquitous Matty Sheets, longtime musical partner Danny Infinger on bass, and her husband, Dave Tippetts, on drums. Another contributor is her friend Brian Kennedy, a Broadway musical conductor and director who tours with Something Rotten! and Wicked. “He happened to be in town,” Vincent says. “I asked, ‘Can you come over right now?’ And he put a crazy organ solo on ‘Shoes,’ one of the songs on the album.”

Vincent is mostly known around the nightclub circuit as a solo artist, her infectious, tangy-twangy crooning winning over a legion of fans as she slugged her way up through the dive bars into widespread acceptance. Last time Eye saw her strumming and singing in her mellifluous tones, she held an audience spellbound at Natty Greene’s, where she was accompanied by bass and drums. “I have a full band now,” Vincent says.

Her ensemble is comprised of Tom Troyer (guitar) and Jared Zehmer (bass), who frequently jams with local rock group Viva la Muerte and a couple of other regional groups.

“Aaron Cummings is a fantastic drummer,” Vincent adds. “He’s going to play on a few songs at The Crown, as will my husband. We’re probably going to have a couple guest spots as well.”

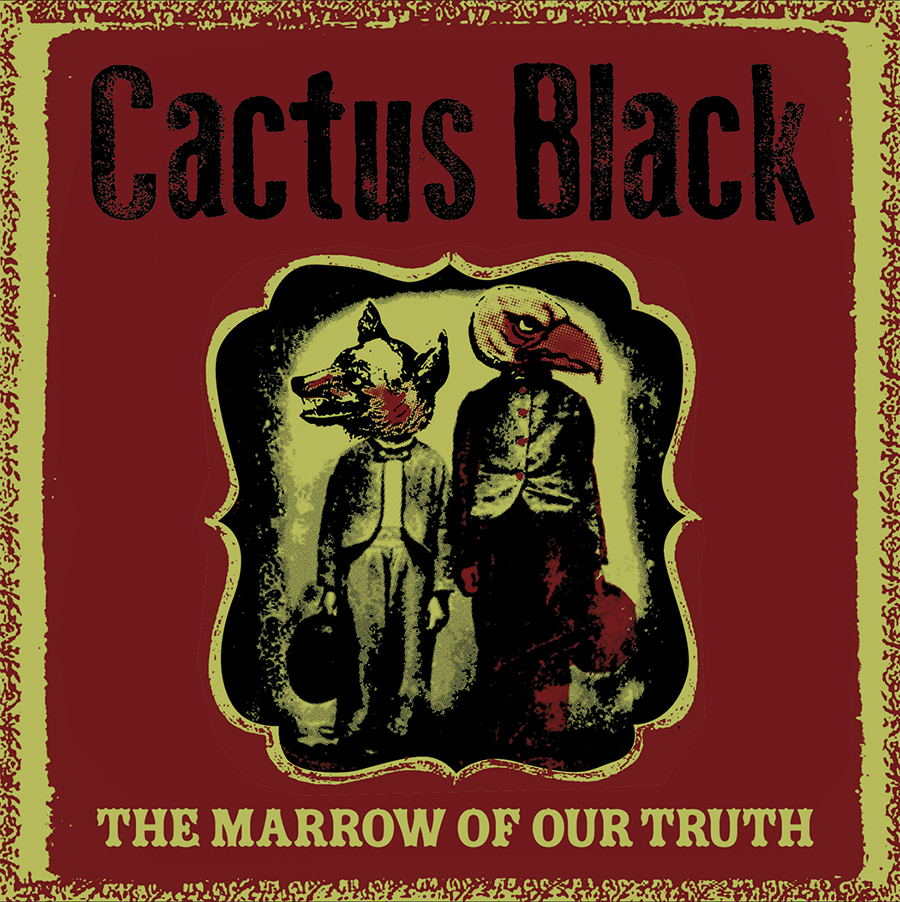

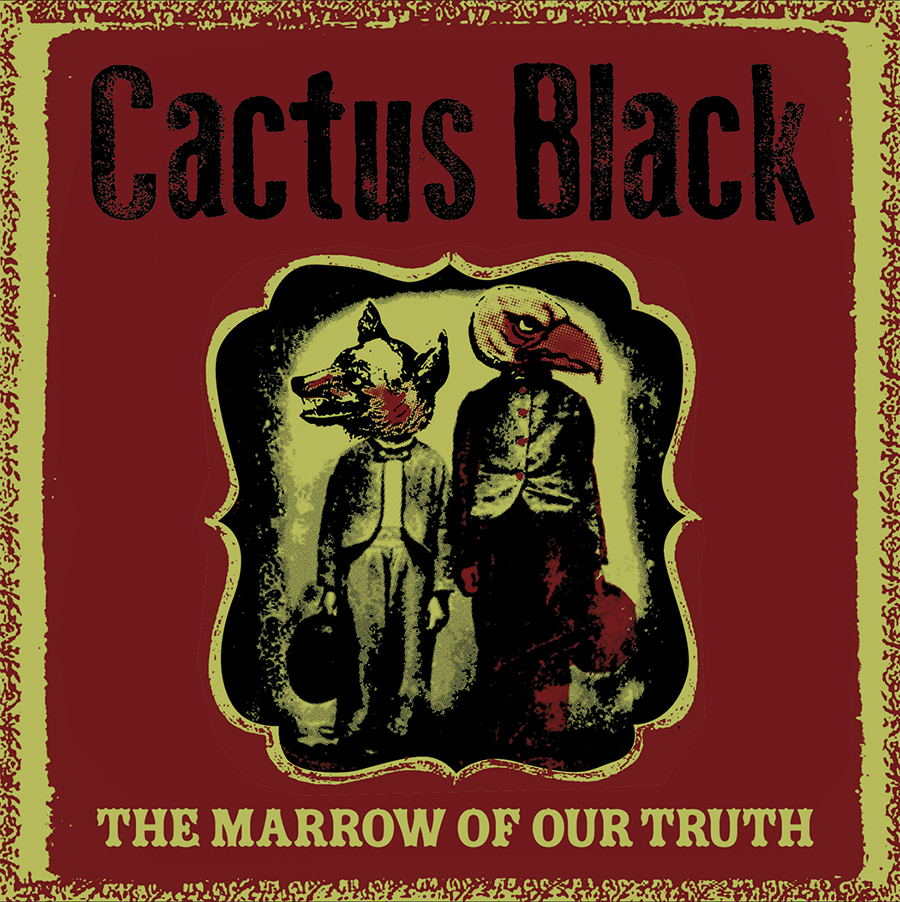

Winston-Salem-based Cactus Black is also on the bill at The Crown that night. I spoke with guitarist and vocalist Mike Tyson, aka Cactus Black, about the band’s rough-hewn, arid desert style. “First and foremost, we’re storytellers rooted in the old country tradition,” Tyson says. “But it’s delivered in more of an indie-rock, garage-rock style, and has kind of a folk influence as well.”

Before coming together as Cactus Black in 2012, Tyson and bandmates Matt Pickard (aka Sunday the Drifter) on drums and Mike Bright (aka Randy Heck) on bass were in a “whiskey rock band” called Tusker. Bright was lead singer.

Cactus Black’s third album, The Marrow of Our Truth, released in August, has quickly become one of my favorites for the sheer exuberance, and inherent intelligence, as well as for being what used to be called a “concept album” — not just anecdotal singles thrown together, but thematic. In this instance: fevered dreams steeped in Old West lore. The opening tune, “All Things Pass, All Things Change,” is a romantically tragic coming-of-age lamentation reminiscent of Leonard Cohen. It’s a splendid party record, superbly paced and deeply enveloping, one that commands (but does not demand) your attention.

“We did a record release show at the Ramkat in Winston back in September,” Tyson says. “There, we played the new record in full. [Sorry I missed that!] This show at the Carolina Crown is going to be a mix of all three records.”

Besides three LPs, the band has a number of singles, one of which is “Live in Greensboro,” a punk-esque jump-and-jive recorded at On Pop of the World Studios and pressed on multicolored vinyl in 2017. Vinyl collectors take note: All of Cactus Black’s releases are beautifully designed and packaged right down to the imaginatively colored discs.

Opening act is local folk rocker Ashley Virginia. Her debut album, And Life Just Goes On Living, plumbs the depths associated with heartbreak and healing.

Vincent admits to being somewhat intimidated.

“I can’t believe I have these two great bands on the same bill as me,” she says. Eye can. And with this amount of talent and superior songwriting on the stage, December 11 should be a night to remember. See you at The Crown, friends. OH

All of the aforementioned artists can be found on bandcamp.com and other digital platforms where you can listen to their entire albums before you buy.

Billy Eye covered the downtown/East L.A. punk and underground music scene from 1980-83 for Data Boy magazine.

Photograph courtesy of Tom Troyer

Laura Jane Vincent is a country girl both at heart and literally, as reflected in her down-home, introspective songwriting.

Laura Jane Vincent is a country girl both at heart and literally, as reflected in her down-home, introspective songwriting.