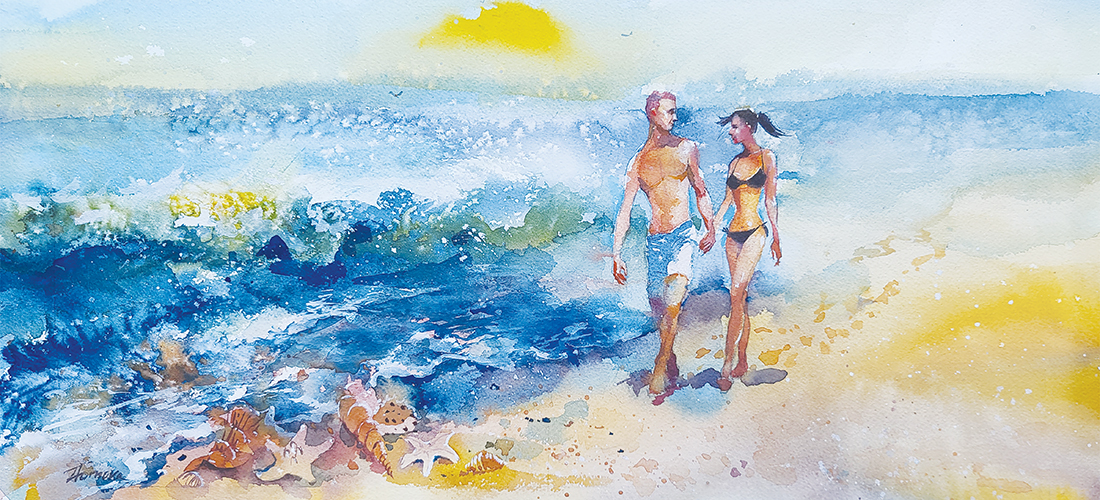

A rustic treehouse getaway for the young — and young at heart

By Maria Johnson • Photographs by John Gessner

Photographs by John Gessner

CHINA GROVE — No offense to Katy O’Neill’s friend, the one with a treehouse back in Durham, where both of the girls live.

Her pal’s loft is pretty swell. It has a slide, and a zip line, and a hammock.

But the treehouse where 8-year-old Katy slept last night was a different story with its comfy beds, plumbed bathroom, kitchenette and flat screen TV.

“This one is a lot fancier,” Katy said before checking out of her family’s overnight accommodations at the Cherry Treesort, a cluster of cabins in the canopy outside of China Grove, a community near Interstate 85 between Greensboro and Charlotte.

Treesort owner Trent Cherry — whose other full-time job is being the head pit crew coach for NASCAR’s Team Penske — built the first treehouse on his hobby farm in 2015 and started renting it out later that year.

Since then, his sylvan community has branched out to include eight cabins: six supported by trees and stilts, plus two “Hobbit Houses” burrowed into a hillside.

Measuring no more than 400 square feet each, the wee lodgings are a hot property on Airbnb, where renters book the properties — at rates ranging from $125 to $195 per night — months in advance.

Guests come from all over. Striding briskly along a trail that connects the cabins, Cherry stops at a posted map of the United States dotted with multicolored push pins denoting the home states of visitors; all 50 states are nubby with pin heads. That’s not counting the visitors from 12 other countries.

“I wish I could tell you our demographics, but when you track it, it’s everybody. We’ve had people come here for birthday parties, anniversaries, honeymoons. Our oldest guest ever was 91 years old,” he says, anticipating the next question. The elderly guest stayed in a hillside cabin connected to the parking area by boardwalk bridge; no climbing needed.

Cherry says the novelty of napping with the squirrels is the property’s main draw — initially at least.

“The treehouses are what get them here,” says Cherry of his customers. “But what they really enjoy is the atmosphere.”

He means simplicity.

“There’s no Wi-Fi here. That’s on purpose,” he says. “We wanted it to be a family place where you can go outside, sit with your kids and turn the electronics off. A lot of parents say, ‘Thank you. We talked, and played board games and card games, and the kids got out and played around the creek and the farm.’”

Would-be renters can tour the treehouses during Winterfest, an open house hosted by Cherry on the first Saturday in December. Bonus attraction: A screening of How the Grinch Stole Christmas on an inflatable screen in a tree-shrouded amphitheater. Nearby, kids spring around in a bouncy house, Santa takes most-wanted updates, a men’s ministry sells barbecue sandwiches and young entrepreneurs hawk wares ranging from mistletoe balls to marshmallow guns.

“Last year, we had 12 kids, and they all sold out. They’d never seen that much money in their lives,” says Cherry, who dresses farmer-chic in roper boots, Carhartt trousers, a dusty Southern States cap and a T-shirt advertising the treehouse community.

“Never Grow Up” the back of the shirt urges.

The kid in Cherry bought these 27 acres, just down the road from his home in China Grove, because he wanted a place for himself and his son, Nick, now 12, to get away.

Cherry’s father, Jim, who owns a T-shirt manufacturing company in Indian Trail, N.C., was not impressed.

“He said, ‘What are you going to do with it?’ I said, ‘I dunno, but I’ll figure it out.’ He said, ‘Well, that’s pretty stupid.’”

A smile floods Cherry’s face: “Now, he loves it.”

Maybe that’s because the adult in Cherry didn’t take long to figure out that he could build a treehouse for himself and his son and rent it out when they weren’t using it.

Soon, he added more leafy lodging.

It also didn’t hurt that Cherry named two of the cabins — Nona’s Nest and Chico’s Hideaway — for his parents, who live in Charlotte. Nona means grandmother in Italian. Chico was his father’s nickname in the Navy.

The other cabins bear the names of dear ones, too.

The Miss Molly is named for Cherry’s daughter, now 10.

The Big Nick — a treehouse and adjunct “guest house” joined by a deck — honors his son.

The Sweet Ashley is named for Cherry’s wife, a kindergarten teacher in Concord. The cabin resembles a one-room schoolhouse.

One of the earthen huts is named Mimi and Papa’s, for Ashley’s parents in Winston-Salem.

The other, Lucy Lu’s Hobbit House, is a nod to the family’s 7-pound Yorkshire Terrier.

“She runs this place,” says Cherry. “She’s the mayor.”

The Lucy Lu might be the most distinctive cabin with its round door and porthole windows peering out from a slope near the main road.

“I came up with that all on my own,” says Cherry. “I saw a picture online of a house built into a hill, and I said, ‘Hell, I’m gonna put a hobbit house in there.’”

The newest treehouse is The Tolson, named for Cherry’s buddy, Doug Tolson, a carpenter who comes from California to help Cherry and a crew of local workers build the cabins at breakneck speed.

“We bust it hard,” says Cherry.

The Tolson went up — literally 10 feet up, into poplars and maples and oaks — in just six weeks.

Cherry insists that the treehouses be supported in part by trees, which usually poke through holes in the decks. Underneath, the trees attach to the houses with sliding brackets that allow the trunks to sway with the wind without twisting the structures.

Cherry bristles at other hosts who bill their rentals as treehouses when the shelters stand on stilts alone.

“Some people build a house in the woods and call it a treehouse,” he declares. “That’s not a treehouse.”

Cherry and Tolson design all of the cabins, scratching out floor plans on napkins, graph paper, scraps of cardboard — whatever’s handy. Cherry sends the drawings to an architect in Charlotte, who polishes the plans, imports them to an app called SketchUp, and ships them back.

A few tweaks later, Cherry and his crew start swinging hammers.

The hideaways are approved by Rowan County inspectors, who also sign off on the well and septic systems. Along with locking doors and windows, most cabins feature a tin roof, wood siding, a deck with furniture, and an outdoor fire pit. Hammocks and swings dangle under the decks.

Inside, the decors are what you might call grain-positive, with wood paneling, wood floors, wood furniture and wood flourishes such as gnarly branches deployed as wall art.

Cherry and his son build all of the furniture, bridges and railings from trees that fall on the property.

“We slab ’em up and make tables and benches,” he says.

Some guests compare the Treesort experience to glamping, or glamorous camping.

“It’s the best parts of camping with all the first-world comforts,” says Lynn O’Neill, the mom of 8-year-old Katy.

O’Neill and her partner, Kathryn Hodskinson, booked one night in a treehouse as a treat for Katy, a fan of the Magic Tree House books.

“We haven’t been anywhere for a year and a half,” said Hodskinson, recounting a stretch of online living because of COVID.

“We needed 24 hours of no Wi-Fi,” added O’Neill.

On the way to China Grove, they stopped at the N.C. Transportation Museum in Spencer. They spent a low-tech evening around the treehouse, reading and cooking hotdogs and SpaghettiOs over a camp stove outside. They used oversize Jenga blocks, which were left on a deck table, to build a house for Katy’s plush toy, Peanut, a mouse from the Magic Tree House.

Hodskinson gave Peanut to Katy as a memento of the trip.

“We’re talking about coming back in the fall, when the colors change,” says Hodskinson.

Just down the dirt road, sisters Jennifer Todd and Amber Kozlowski, both of whom live in the area, were preparing to check out of The Big Nick duplex after a birthday sleepover with seven girls, including Todd’s daughter, Addison, the honoree who was turning 11 in a few days.

The guests included Addison’s cousin, Savannah, along with Addison’s friends Remi, Makenna, Sophie, Kierra and McKinley.

For dinner the night before, the preteen tribe roasted hotdogs and s’mores over the fire pit.

Guided by fireflies and bistro lights strung up around the cabins, the girls played hide-and-go-seek in the woods, twirled in swings and watched Barbie videos on their phones until their batteries died; alas, the flat-screen TV in their cabin was hitched only to an antennae and DVD player, not to cable or dish service.

They fueled their all-nighter with Goldfish crackers, Cheetos, cupcakes, Cheerwine and an occasional foray outside to throw each other’s Crocs clogs off the deck. There also was a brief interlude with a yellow jacket wasp that crashed the party.

A good time was had by all, except the dearly departed yellow jacket. The cabins — though hot and stuffy at times despite electric fans and split-unit heating and cooling — passed muster with their “rustic vibes,” according to the girls.

“My favorite part was just being in nature,” says 8-year-old Savannah. OH

Maria Johnson is a contributing editor of O.Henry magazine. She can be reached at ohenrymaria@gmail.com.