Simple Life

The Dash of Life

by Jim Dodson

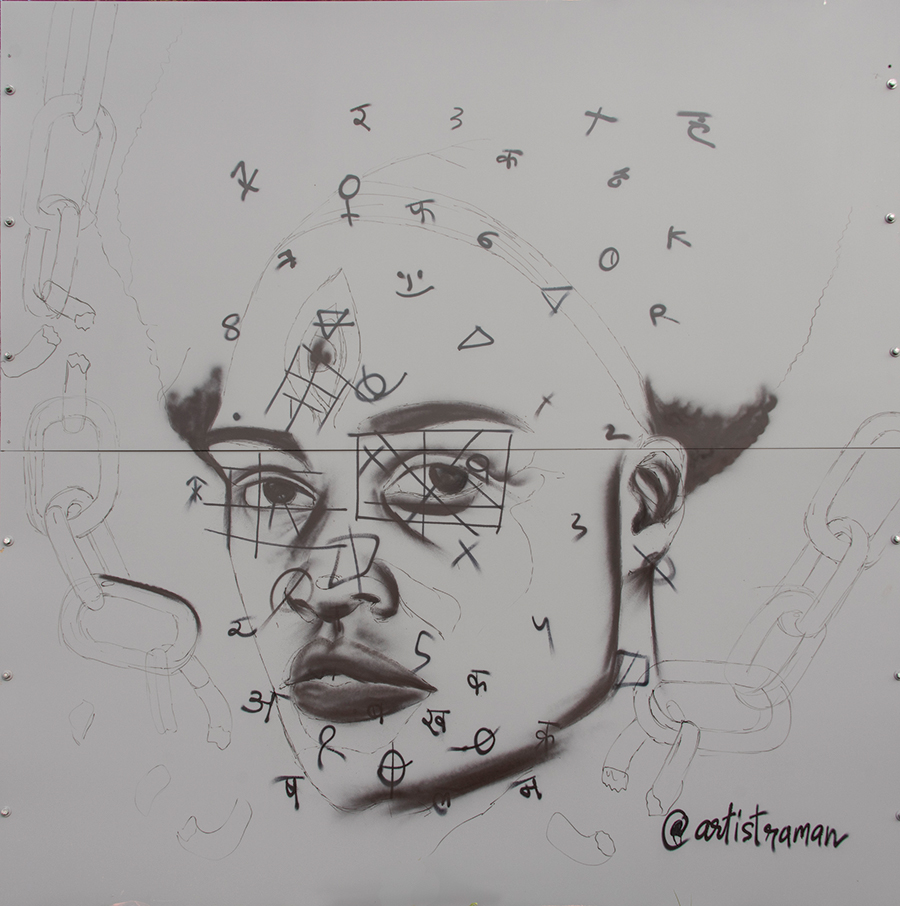

In an early episode from one my favorite British dramas, a charming program called “Delicious,” a roguish head chef, speaking from his grave in a Cornwall churchyard, muses on the symbolism of markings in stone.

“On a gravestone you see two dates – a beginning and an end, with a tiny dash in between. That dash represents everything you’ve ever done. Everywhere you’ve ever been. Every breath, kiss or meal between birth and death. It all boils down to just one little dash…”

As a veteran wanderer of ancient burying grounds and longtime collector of clever epitaphs, I decided years ago that gravestones “speak” about the lives contained therein, telling tales and offering wisdom to those who will listen.

Or sometimes just a much needed smile.

Here’s one I fancy from a Wolverhampton churchyard dated 1690:

Here lies the bones of Joseph Jones

Who ate whilst he was able;

But once o’er fed,

He drop’t down dead

And fell beneath the table.

When from the tomb,

To meet his doom,

He rises amidst sinners;

Since he must dwell

In heav’n or hell,

Take him – which gives best dinners!

At a moment when more than 200,000 of our fellow citizens have succumbed to the Covid virus, the subject of death is hardly a laughing matter. For most of us, in fact, the question of one’s mortality is one we would politely defer …indefinitely.

Yet when the end comes – delivered by a killer pandemic or a slowly ebbing pulse from natural causes — the meaning of the dash may suddenly become clear.

Life is brief, as an Irish friend likes to say – and subject to change without notice.

Out west over the past few weeks, more than 150 wildfires incinerated thousands of homes and property, burned up lives and landscape roughly the size of New Hampshire, forcing half a million people to flee for their lives. At last count, more than 100 people perished and dozens more are unaccounted for from the apocalyptic inferno, which is already in the books as one of North America’s worst natural disasters.

Some say it’s merely a preview of things to come.

Every credible environmental scientist – an endangered species in their own right – agrees that we have reached a perilous breaking point in terms of protecting the life of the planet from our own ecological abuses. As California and Oregon burned, a report all but overlooked from the International Wildlife Foundation noted that since 1970 more than 70 percent of the planet’s wildlife has vanished, including dozens of species that have gone extinct. Moreover, man’s invasion of remaining wild places threatens to see more exotic killer viruses jump between species.

Meanwhile, down on the Gulf Coast, a series of hurricanes have battered the Alabama and Florida coastlines this month, flooding streets with biblical-sized rainfall and destroying untold numbers of lives and property, with more death and destruction on the way from a deadly conga line of tropical cyclones coming off the west coast of Africa. According to the NOAA, barely halfway through the tropical cyclone season, for only the second time in recorded history, authorities have run out of assigned names and turned to the Greek alphabet to identify further storms this season, the Alpha and Omega of natural disasters.

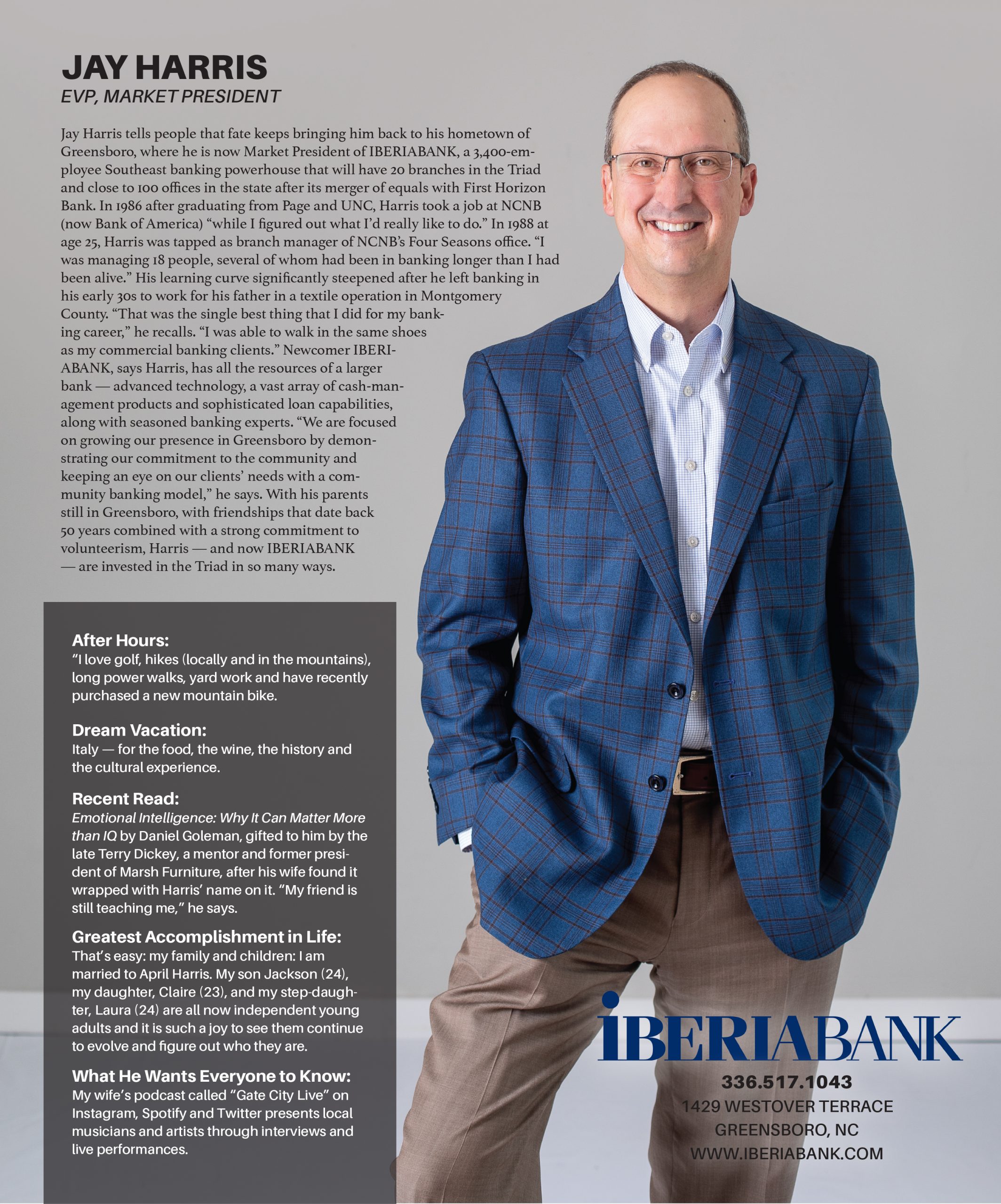

I have a hunch Bill Buynak would have been fascinated.

Bill was my father-in-law.

Earlier this month, quietly and without much fanfare, in the midst of all this cinematic death and destruction, he passed away from a lengthy heart ailment. He was 85.

Though we disagreed on global warming, Bill and I enjoyed talking about the drama of weather and debating sports, two subjects where we found comfortable common ground. For that matter, we could also talk history and even religion since Bill was a well-read man who fiercely embraced his Catholic faith.

Of the three dining room table taboos guaranteed to ruin any holiday gathering – sex, religion and politics – only politics was the true buzz killer, especially at Thanksgiving when big Bill occupied the head of the table.

I learned this several years ago when I made a lame joke about Sarah Palin and watched Bill simply rise and leave the room. We heard the front door open and shut. He walked home.

A long life may not be good enough, Benjamin Franklin was supposed to have said. But a good life is long enough.

Joseph William “Bill” Buynak certainly had a good life.

I knew him for more than 20 years. But it took his passing, I regret to say, for me to learn who he really was – the dash of his life, if you will, between his birth and passing.

Bill grew up in a working-class neighborhood of Bridgeport, Connecticut, the son of Czech and Lithuanian immigrants, joining the army after high school to become a top instructor at the army’s famous Fort Dix Radio School.

Electronics and computers were his career passions. He went on to become a computer engineer and worked for one of the country’s pioneering computer firms, earning several key patents on a mobile sports graphic program still in use today.

Music was his deeper passion. As teenager, he played accordion in a polka band and apparently could dance like nobody’s business. That may be how he wooed and won the hand of his bride of 55 years, Jeannette Ward, a spunky Irish lass.

His oldest daughter, my wife Wendy, remembers how after she and her two sisters Karen and Amy had had their evening baths, they would come downstairs in their nightgowns and dance to Russian folks dances their papa played on his state-of-the-art stereo. His record collection was vast, more than 500 LPs from every genre — Bach to the Beatles, ZZ Top to Gustav Mahler.

On Sunday mornings, big Bill would slip out to get The New York Times and fresh baked Kaiser rolls from the local deli, putting on an opera called Peter Grimes – a tale about a fisherman who gets lost at sea – to awaken the household.

As teenagers, Bill taught his girls how to play tennis and drove them to Vermont to properly learn skiing. “He was surrounded by strong-willed women,” Wendy points out. “We had him out-numbered four to one. But he never complained. He also documented everything.”

Being a true tech geek (Star Trek was naturally his favorite TV show) Bill was filming the life of his young family years before video cameras became the rage of suburban America. Not long before his passing, Wendy and her papa transposed some of his early 8-millimeter films of family gatherings, anniversaries and birthdays to digital.

“Everyone looks so young. What a handsome guy he was,” Jan Buynak murmured wistfully as she watched her husband’s restored film. True to form, Big Bill Buynak makes only brief and momentary appearances in the watery film. For in more ways than one, he was always the man quietly behind the scenes.

Due to Covid-19, Bill’s memorial service has been postponed to sometime next year back home in Connecticut.

Given this upside-down year in which weddings and funerals and every thing between have been delayed, postponed or simply cancelled, it’s uncertain if an actual grave stone will someday mark Bill’s final resting place in a veteran’s cemetery in Virginia, with a pair of dates and a dash in stone to speak of his well-lived life.

His one wish was to make it to this year’s Thanksgiving table.

We plan to honor that wish, placing his boxed ashes at the head of the table.

Parts of this “Simple Life” were adapted from a previous publication in May 2018.