Profile of an up-and-coming Greensboro influencer

By Maria Johnson

Photographs by John Gessner

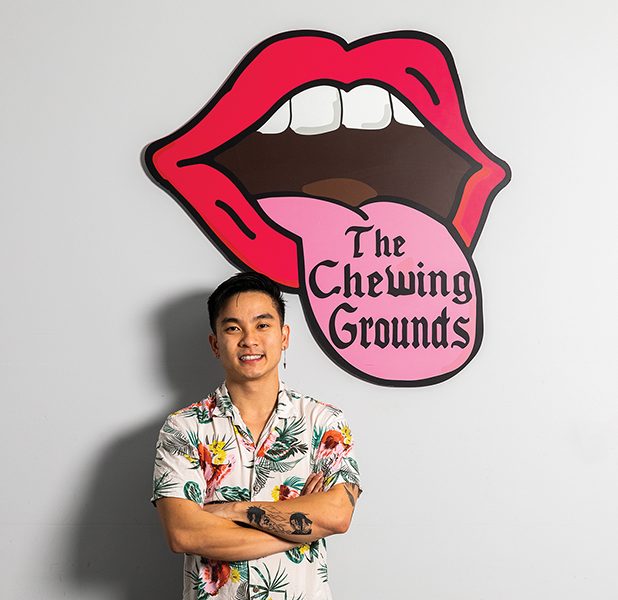

As they prep for a podcast called “The Chewing Grounds,” host Luan K. Do (just call him Loon) and his guest, Griffen Glover, are hanging out in the show’s green room, which is actually the living room of Loon’s brand new, three-bedroom, two-bath, still-smells-like-paint home in southwest Greensboro.

As they prep for a podcast called “The Chewing Grounds,” host Luan K. Do (just call him Loon) and his guest, Griffen Glover, are hanging out in the show’s green room, which is actually the living room of Loon’s brand new, three-bedroom, two-bath, still-smells-like-paint home in southwest Greensboro.

The guys are pumped, literally, having just returned from an upper-body workout at the gym where Griffen, Loon’s friend since first grade, used to work as a trainer. The chat turns to social media and how many followers Loon has across all platforms.

Instagram? Probably 21,000 or 22,000 people, Loon estimates.

His YouTube channel? Maybe 5,000 subscribers.

“Does Facebook count?” Loon muses. “I really don’t use Facebook or LinkedIn any more.”

“Do you have TikTok?” Griffen quizzes.

“I have the app, but I don’t really focus on it,” says Loon. “I need to, but I want to pay someone to do it . . . Dude, it’s the future. It sucks, but it’s the future.”

Loon consults the invisible calculator in his head. Yeah, he confirms, he definitely has fewer than 40,000 followers/friends/contacts, which lands him squarely in the territory of “micro-influencer,” meaning he makes money — an average of $200 a month — by posting social-media content that attracts viewers and thus advertisers, but not as much money as a “macro-influencer,” or someone with an audience of 100,000 or more, a status that Loon, at the ripe old age of 25, hopes to reach.

“Maybe in a couple of years,” he says. “If I could do that, it would be amazing.”

But first things first. It’s time to record the podcast. The guys walk a few steps into the studio, aka Loon’s kitchen. They perch on low-backed stools, facing each other across a breakfast bar and pull on headphones. Two cameras — iPhones mounted on tripods — are trained on them. Later, Loon will edit the video into a split-screen view for YouTube. The audio will be uploaded onto multiple podcast platforms.

To start recording, Loon hits a button on the digital mixing board in front of him, pops an energy drink next to a microphone — fizzzzzz — pours the contents into a couple of ice-filled glasses, hands one to Griffen, offers cheers, and slides into the unscripted frolic that begins with recollections of an elementary school field trip, sidesteps into a promo for their “strawbango” flavored drink — “This would go good with alcohol,” Loon offers — and pivots into a long gym-bro discussion of fitness.

“How much you weigh right now?” Loon asks.

“One seventy-three.”

“What’s the biggest you ever got?”

“One seventy-five.”

Loon exhales with admiration. “Do you ever get, like, sweats?”

“No.”

“That’s immaculate,” Loon says. “The highest I’ve ever, ever pushed myself was 165, and I felt like dog shit. I was sweating, and the sweat smelled bad, like pizza grease.”

Online life comes naturally to Loon, who spells his name like the bird because it’s the correct pronunciation of his given name, Luan, which most Americans butcher along with his last name, Do, pronounced “dough.”

Born in 1997, at the dawn of Gen Z, Loon remembers seeing his family’s first computer in the early 2000s. He was 5 or 6 years old. The machine was an outdated desktop, probably bought at a discount, with a monitor that reminded Loon of a humungous human head.

“The keyboard was dinky-dinky,” he says. “We’ll go to a museum where they’ll talk about technology, and I’ll be like, ‘That was in my house.’”

He played video games such as “Galaga” and watched turn-of-the-century movies, including Shrek and Rush Hour, on pirated CD-ROM disks provided by a family friend.

When he was about 10, he got his first cell phone, a hand-me-down Nokia that looked like a small calculator. It had a screen, buttons and offered one game, Tetris, in black-and-white.

He also created an account on Myspace, an early social-networking site.

“It was a dumpster fire of the randomest things ever,” he laughs, adding, “You could make your background really cool.”

At age 12, he owned an Xbox video gaming console and started a YouTube channel to post tutorials on how to build teams with bargain-basement players in the FIFA video soccer games. He drew a lot of negative feedback.

“They could tell I was a kid, and that I had no actual knowledge of soccer,” he says. “And I couldn’t pronounce anyone’s name.”

With his father working as a licensed plumber and his mother working in a factory that made car parts, Loon says he and older sister Thao were spoiled — with an asterisk.

They got as many material things as their parents could afford on a limited budget.

They also got spanked and grounded if they brought home disappointing grades.

“Asian-spoiled is not like American-spoiled,” Loon says. “I got to struggle, but I didn’t get to struggle like my parents.”

Loon’s father, Quang, was one of nearly a million “boat people,” refugees who fled war-ravaged Vietnam after America ended its presence in 1975.

He spent seven years in a Malaysian refugee camp known as “Hell Isle” before the camp started repatriating refugees. Quang went back to Vietnam, where he met Loon’s mother, Suong Tran. They started a family and finally got a chance to immigrate to the U.S. in 1998, after a Lutheran church in High Point agreed to sponsor them. Loon was 13 months old.

The family lived in a string of apartments before buying a small home off of Merritt Drive in Greensboro. Loon made it through Western Guilford High School with minimal corporal punishment at home — thanks to a combination of charm and cheating in class, he says. He took a student loan to attend UNC Wilmington, where he majored in business and pledged a fraternity.

“I was trying really to be an American white kid,” he says. “I found myself later.”

After selling insurance for a summer.

After becoming a personal trainer.

After figuring out that he wanted to work for himself.

“I don’t like working for someone who’s working for someone who’s working for someone,” he says. “Everyone is only looking out for themselves. They’re like, ‘Oh, you need to do better so I can look good.’”

His role model for self-employment, he says, is his sister, Thao, who’s 10 years older and whom he describes as “a superstar,” “a beast,” and “a juggernaut.” A graduate of UNCG, she owns two nail salons, a waxing studio and a beauty school. She hired her little brother to help manage the businesses about the time he rediscovered the magic of YouTube — as both a consumer and producer.

“I learned everything I know from YouTube,” he says flatly. “I don’t read.”

In 2016, he started posting fitness video blogs, or vlogs. Some focused on body-building. Some focused on healthy food. The nutrition pieces got more clicks.

Viewers also gobbled up the restaurant scenes he shared from a Los Angeles trip.

“I actually got, like, 7,000 views, which is high for my channel. I usually get, like, 2,000 or 3,000,” he says.

Loon saw a market for city-based food vlogs. Ahead of a trip to Atlanta, he arranged for restaurants to give him free meals in exchange for exposure.

In Cary, a pizzeria gave him food and $50 to boot.

In Raleigh, he did a four-part feature and asked each place for food and $100.

“I did 16 restaurants in Raleigh, and I made, like, $1,400,” he says.

As his YouTube subscriber base grew, YouTube started placing targeted ads in his vlogs and paying him based on the number of views.

He expanded his audience, calling ahead to establishments in Chicago, Cleveland, Miami and New York. He did the same when traveling abroad.

In vlogs full of jump cuts, spastic camera work, overlaid music and occasional segues nicked from the Sponge Bob cartoon — “twen-ty minutes lay-tah . . .” — viewers watched him eat, drink and be merry in England, France, Italy and Greece.

His focus wasn’t entirely commercial, though.

Some vlogs amounted to home movies.

“Carolina Beach Travel Blog 2021” captures a family trip to celebrate his niece’s sixth birthday.

“Guess What I Got!” focuses on opening Christmas presents and making cookies at his sister’s house a few months later.

Those are the vlogs he shows his parents, whose grasp of English is limited.

“I want to make my family proud,” he says.

His parents were happy, he says, when he showed them an Instagram video he produced for Crest toothpaste and Reach toothbrushes. The mini-commercial shows Loon forgetting his dental kit on a trip, then jumping for joy when the self-propelled toothbrush and toothpaste — they’re being pulled by a barely visible thread — catch up to him.

He made more than $1,000 for the spot.

“They paid you that much — for that?” his mother said in Vietnamese when he showed her.

His father smirked his approval, Loon says.

They also beamed when they saw him earlier this year on I Can See Your Voice, the Fox network’s TV game show hosted by Korean-American comedian Ken Jeong, who spent some of his formative years in Greensboro.

Loon is pretty sure his Instagram numbers — along with his age, gender and race — caught the eye of the show’s casting agent. The Greensboro connection probably didn’t hurt. Loon lasted for one episode and brought home $15,000, which he promptly applied to his home’s mortgage.

The outstanding balance is not as much as you might guess. Loon’s down payment was more than a third of the home’s cost because he cashed out part of his investment in the electric car company Tesla. Loon learned about the company and its founder Elon Musk — whom Loon jokingly calls “Daddy Elon” — by watching YouTube videos.

Still a shareholder, Loon says he has doubled his Tesla money since 2019. He also holds blue-chip stocks like Apple and Microsoft.

“I’m not book smart,” Loon says. “But I’m really street smart.”

To share the secrets of his financial success, he launched a YouTube channel devoted to personal money management in 2020. Shedding his earrings and covering his tattoos with a white shirt, suit and tie, he told the story of how he paid off the loan for his slightly-used car in three years.

“I’m a very frugal person, very minimalist,” he explained, exhorting viewers to follow his example. “Do anything you possibly can to lower your expenses. Don’t worry about the now. Worry about the later.”

The financial channel never caught on, but Loon is still devoted to building his coffers.

He plans to buy another house, move into it and rent the one he occupies now. He wants to repeat the process until he owns several homes and lives off the rental income.

At that point, his payments from social media will be gravy. A bigger payoff will be a heightened profile — he’s easily the most visible Asian person on social media in this area — and more connections to other influencers, brands and communities.

“I see it as a means to everything,” he says. “It satisfies my need for attention, but it also gives me so many fun adventure opportunities.”

He’s cutting back on food and travel vlogs to focus on other projects. One is stand-up comedy.

“I have material. It’s just a matter of time,” he says. “I’m also getting a license to tattoo. These are all side quests.”

He plans to continue the podcast, which sports a mouth-and-tongue logo strikingly similar to The Rolling Stones trademarked “hot lips” emblem.

Loon says he had no idea about the resemblance until his then-6-year-old niece Lana was shopping and saw a phone case bearing the rock band’s logo.

“Oh, my God,” she told her mother. “Uncle Loon is famous.”

With more than 70 podcast episodes completed — most running at least one hour — Loon dips into a reservoir of people he knows well, those he barely knows and those he wants to know. Conversations range from raunchy to wonky, from sketchy to touching.

Previous guests include former Greensboro mayoral candidate Justin Outling; Asian country singer Travis Yee of Las Vegas; and Loon’s best friend and roommate, Zoran Kulic, whom he has interviewed at least three times.

“He’s the perfect person when I can’t find another guest,” Loon says.

Then there’s Griffen, his friend from first grade, who is featured in episode No. 62.

The topics swing wildly, touching briefly on what Loon describes as Griffen’s “really good morals.” Loon wonders aloud how Griffen was affected by his dad’s death at an early age.

“I just know, him looking down on me, he’d want me to continue going,” Griffen says.

“Dude, that’s immaculate,” says Loon, speaking so quickly it’s almost indecipherable.

Then they’re off to trendier pastures.

One week later, the show appears under the provocative title, “Guns, Cults and How to Lose Weight Easily.” OH