By Jim Dodson • Photograph by Lynn Donovan

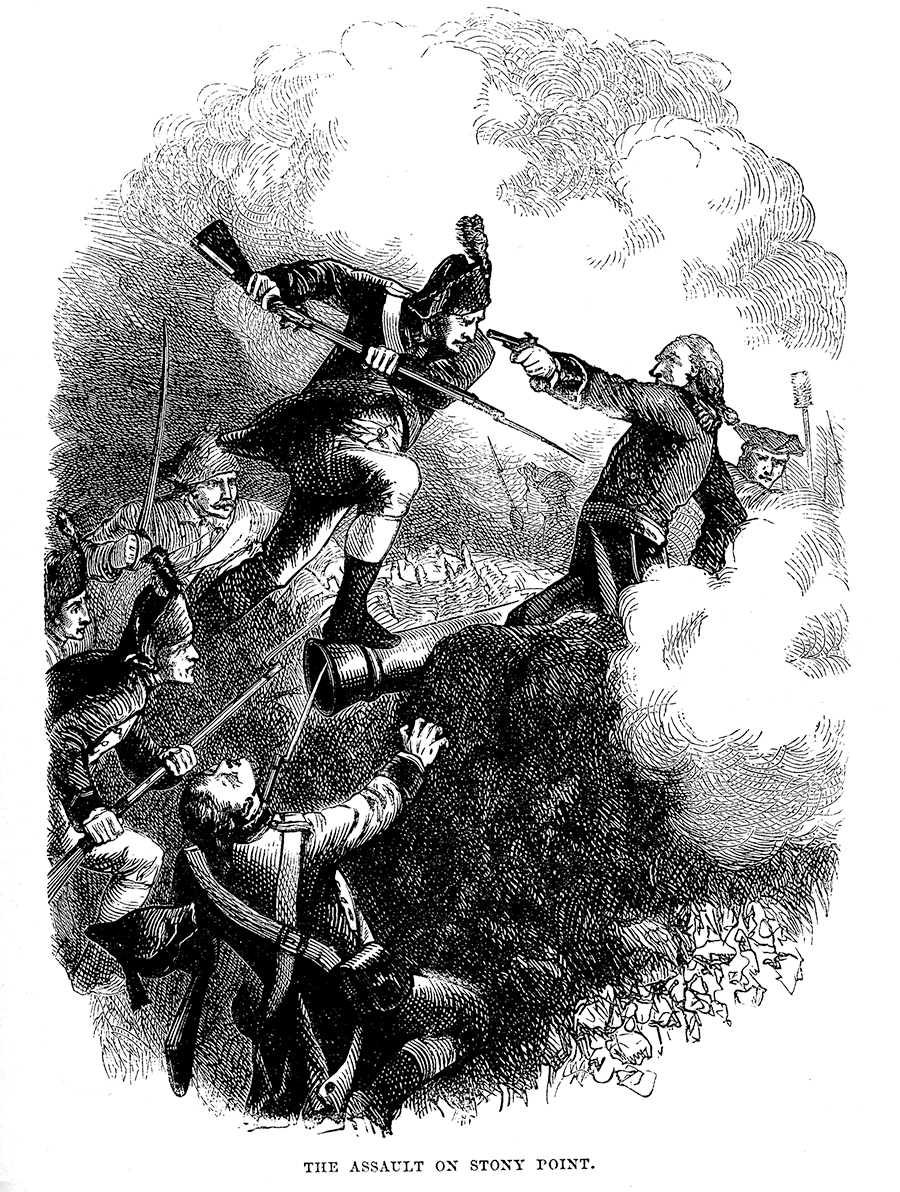

Many of us had the great fortune to grow up with the historic Guilford Battleground in our backyard, the place where the city’s namesake General Nathanael Greene met British General Cornwallis’ army. The fateful showdown on March 15, 1781, helped turn the tide of the Revolutionary War in favor of the Patriot struggle for independence from Great Britain. Today, when you are driving over streets named New Garden and Battleground or through neighborhoods called Kirkwood and British Woods, you are covering bloody ground where arguably the pivotal battle for American independence took place. One local story holds that the name “Brassfield” derives from brass military ornaments recovered in the vicinity of Horse Pen Creek where the shopping center exists today.

If you’ve never witnessed the battle’s annual series of re-enactments live, an event that attracts hundreds of “Rev War” re-enactors and battlefield buffs from across the nation to what is now officially called Guilford Courthouse National Military Park, you are in for a real treat. It’s the perfect mix of history and military pageantry on an early spring day.

Jay Callaham not only happens to be an expert on military history and a veteran re-enactor of more than 50 years, but also the narrator of the action at Guilford Courthouse for approaching 20 years. Among other things, he also served as an advisor on the film The Patriot. Callaham portrays an officer of the Coldstream Guards, and for many years acted as a British field commander, and has performed the role of Lord Cornwallis. During his nearly 20 years of narrating the battle presentations, he is typically uniformed as a British Officer.

We caught up to the retired communications executive and former Army major on a recent afternoon at the Greensboro Masonic Temple on Market Street, wondering if there might be 10 curious and lesser-known facts about the famous battle.

Lord Callaham happily obliged.

1. The Super Bowl of the Revolutionary War

By the time Cornwallis marched his troops to Deep River Friends, where he camped prior to the battle, having unsuccessfully engaged General Greene’s army for six weeks across the Carolinas to the Dan River and back, both armies were showing serious wear and tear. “Both were in pretty terrible shape. Cornwallis halted his march in Salisbury, for example, just to find shoes for his troops. As they came through Old Salem,” notes Callaham, “the British and their camp followers stole clothes off lines. Despite their worn appearance, Cornwallis’ 33rd Regiment was among the best in the world. His force included the renowned Royal Welch Fusiliers, and veteran 71st Highland Regiment, as well as the battle-hardened Brigade of Guards and Hessian Regiment von Bose (pronounced bose-a), all led by seasoned commanders. Not to mention American Loyalist or Tory troops. Greene’s force was a mix of militia troops from the Carolinas and Virginia, many of whom had prior experience and training in the Continental Army, as well as the 1st and 2nd Maryland Continental Regiments and Kirkwood’s Delaware Continentals. One army was led by a British General who’d never lost a fight in the field, the other by a Colonial general who’d never won a fight in the field — and wouldn’t win this one. In many respects, despite their tattered condition, this was the Super Bowl of the American Revolution, the battle that changed the whole complexion of the war and brought it to a close.

2. The Myth that the North Carolina Militia failed to hold its ground.

In his report following the battle, General Greene asserted that the front line of the deployed Americans — manned by the North Carolina Militia — failed to hold its ground during the first assault by the British. “He wrote that the Carolina militia broke and ran at the start of the action. It’s simply not true,” says Callaham. “They weren’t even a true militia, rather a mix of local farmers and tradesmen and highly seasoned Continental troops that had proven themselves in plenty of action. They were deployed behind split rail fences overlooking Horse Pen Creek. The next line up was the Virginia militia followed by the 1st and 2nd Maryland. The commander of the 71st Highland Regiment — one of the finest units in the British army — reported that the lost half his company in the first volley. The North Carolina Militia troops did their job splendidly, in fact, enduring a 30-minute cannonade from three-pounder Royal Artillery cannons. Greene was simply trying to cover his rear end for losing the battle, which broke out everywhere and was mostly one of complete chaos. Fighting was brutal and bloody, hand-to-hand at times.”

3. The Scope of the Battlefield

The scope of the battlefield was huge, stretching from New Garden Friends — where Kirkwood’s Delaware troops engaged along New Garden Road — to the Guilford Courthouse site, a distance of about four miles. Cornwallis’s 2,000 troops were deployed along what is now Battleground Avenue, roughly from where Lowe’s Home Improvement is today all the way to Walmart. Artifacts from the battle have been found around both big box stores and along Battleground. The national battlefield encompasses only about a third of the actual battleground, and does not include skirmish sites along New Garden Road. Other parts of the battlefield are under Forest Lawn Cemetery and Greensboro Jaycee Park, both places where many artifacts have been found.

4. Rifles vs. Muskets

Soldiers in both armies used similar weapons, mostly muskets made in France or the venerable British Brown Bess muskets commonly used by infantrymen on both sides. Muskets fired a ball about three-quarters of an inch in diameter, loaded from paper cartridges containing powder and bullet or buckshot, rammed down the unrifled, smooth-bore barrel to the breech. A skilled fighter with a musket could load and fire his musket three times within a minute. The musket had an auxiliary weapon as well — a fixed bayonet — used effectively by the tenacious 1st Maryland at the Battle of Guilford (though by the 18th century, deaths in battle from bayonets were becoming less common). Rifles were a more specialized weapon, defined by a barrel with twisted grooves along its interior that allowed for a more accurate shot. The problem was a slower loading process that could be problematic in close-quarter fighting. On the other hand, rifles had extended ranges of accuracy — up to 300 yards — and were used effectively by both sides during Britain’s failed Southern Campaign, whose objective was to sever the South from the North, destroying the “bread basket” of the Colonial Army and ending the war in Britain’s favor. Rifles affected the outcome of at least three major Southern battles — at Kings Mountain, Cowpens in South Carolina and to some extent Guilford Courthouse, where the British used Jäger riflemen from Germany to great effect. These were skilled hunters dressed in green, whose deadly accuracy and discipline made them formidable foes. “The Jägers were professional huntsmen and were crack shots. The problem was every rifle had its own caliber, which often meant a rifleman had to make his own ammunition. Rifles played a significant role but muskets and bayonets won the war,” says Callaham.

5. Question: Which Side was dressed in Blue? Answer: Both sides

A key regiment of the British force at Guilford that saw intense action was the von Bose regiment composed of well-drilled German soldiers who wore dark blue uniforms that resembled the uniforms worn by both the Colonial Army, and both British and Continental artillery units — producing confusion in the fog of battle. The British army’s uniforms were bright red so they would stand out in the smoke of battle. The proud von Bose unit was composed of Hessians who came from a number of places across Germany, leased to the British army by King George III’s German allies. Fighting on the right flank of the advancing British force, the von Bose unit was savagely attacked both front and back by the Americans, distinguishing themselves and affecting the outcome of the battle. “Contrary to the myth, these troops were not mercenaries. They belonged to the lord of their home principality. An interesting postscript: Most Hessians who were captured were sent as prisoners to Pennsylvania where German farmers employed them. Many were encouraged to stay in America and were even given land. Many became American citizens.”

6. Did Cornwallis really fire upon his own troops?

Not intentionally, insists Callaham. “That’s one of the biggest myths about the battle. At one point in the battle, he came upon a melee in close combat between the 2nd Battalion of the Guards and 1st Maryland and ordered his soldiers to use a 3-pounder [cannon] to fire on Lt. Col William Washington’s light dragoons [calvary] that had attacked the Guards and in so doing had come between Cornwallis and his troops. Cannon doesn’t discriminate between red and blue. But the decision halted the Dragoons, separated the Guards from the 1st Maryland, prompting Greene to leave the field to preserve his Continental troops — and allowed Cornwallis to escape. It would have been very bad for the British if he’d been killed or taken prisoner. General Cornwallis also had at least one horse shot out from under him and was almost captured during the confused fighting in the woods. The fighting was that intense, neither side yielding, convincing General Greene to leave the field, in good order, to preserve his Continental troops.

7. Light Horse Harry Lee vs. Banastre Tarleton

Both were legendary cavalrymen. Tarleton was commander of the green-clad British Legion and the subject of a rebel American campaign, which claimed that his men terrorized the countryside and massacred surrendering Continental Army troops at the Battle of Waxhaws, South Carolina, in 1780. The alleged outrage earned him the nickname “Bloody Ban.” As leader of the highly mobile Continental Light Dragoons, cavalry and infantry, Lee won fame for his hit-and-run guerilla-style harassment that helped stymie the British army during General Greene’s “Race to the Dan.” Both men saw action at Guilford Courthouse. Both men presided over the massacre of unarmed soldiers — Tarleton at Waxhaws, Lee in Alamance County, whose Legions cut down a large group of royalist volunteers marching to join up with Cornwallis, camped in Hillsborough, N.C. before returning to Guilford County. “Light Horse Harry’s Legion basically slaughtered them, hacked them to pieces,” Calaham says. Adding insult to injury, the survivors were fired upon by British sentries when they sought shelter with Cornwallis. Harry Lee went on to become governor of Virginia and father to Robert E. Lee. Tarleton lost two fingers on his right hand in the battle at Guilford Courthouse and back home was elected to Parliament. “The truth of the matter is, Harry Lee wasn’t as great as he’s made out to be and Tarleton wasn’t as bad,” Callaham allows. Lee, he notes, was a terrible businessman who went bankrupt and nearly lost the Lee family estate, Stratford Hall — placed in trust, allowing Henry Lee IV to inherit it. “Tarleton had taken the town of Charlottesville, Virginia on a raid prior to the investment of the army at Yorktown. He had also taken Monticello, and could have destroyed it, but didn’t. There were good and bad men on both sides of the fight. The war brought out both aspects in them.”

8. The Numbers Game

No one knows for sure how many men were involved in the Battle of Guilford Courthouse, but the accepted number includes 4,000 Patriots and 1,700 men fighting for the Crown. “They were the best troops in both armies,” says Callaham, “the most elite troops with the best leaders. One of the most fascinating aspects is the disparity in their numbers.” The Brigade of Guards went into the battle with about 700 men and lost almost 50 percent of them — their worst day in the war, in part because the Americans had roughly a 2-to-1 advantage in numbers. “Traditional battlefield strategy holds that, if you’re going to attack an enemy, you should have at least a 3-to-1 superiority. Cornwallis had almost a 50 percent inferiority in numbers and still won the battle.” That was good news for the visitors. The bad news is that the British general lost a quarter of his troops. They were never quite the same after that. After withdrawing to Wilmington to rest and refit, Cornwallis abandoned the Carolinas, and moved into Virginia, joining his troops to another British force. Before marching into Virginia. Weeks later, Cornwallis surrendered 7,000 troops at Yorktown, ending the war.

9. A Dark Legacy

Col. Charles Lynch was also present at the Battle of Guilford Courthouse, commander of a rifle unit for the Virginia militia, a planter-class judge who was infamous for the harsh brand of frontier justice he meted out to British spies and Tories during and after the war. Lynch coined the phrase “Lynch’s Law” to describe the hasty trials and punishment he meted out, particularly if the sympathizer happened to be a loyalist. Legend holds that his worst offenders were tied by their thumbs to branches of a black walnut tree and given 39 lashes with a whip known as the cat o’nine tails. If the convicted individual hollered “Liberty forever!”, so the story went, he would be spared the remaining lashes and forced to enter American military service for one year. “Basically,” says Jay Callaham, “he loved to hang Tories.” The term “Lynching” is commonly believed to have derived from his name and dark legacy. A young Sam Houston — who later avenged the Alamo and gave his name to the largest city in Texas, saw his first action as a sharpshooter serving in the Virginia Rifles at Guilford. Supposedly, he walked home to western Virginia after the battle.

10. On and a brighter note, Spring is back — Let’s Play Ball!

After you’ve checked out this year’s re-enactment scheduled on Saturday, March 16 and, Sunday, March 17, weather permitting, why not be a super patriot and show up for opening day of our beloved Greensboro Grasshoppers on Thursday, April 4, at 7 p.m.? The Hoppers, at least in part, take their name for the highly mobile and effective 3-pounder cannon used so effectively by the Americans at the Battle of Guilford Courthouse. Look sharp and you’ll find the replica of the famous cannon owner Donald Moore acquired for the occasion. “Our park, after all, sits only five or six miles from the scene of the battle,” says Moore with a laugh. “You probably could have heard the cannon fire from home plate — if there’d been one in those days.”

O.Henry Editor Jim Dodson has attended two re-enactments — one almost two decades ago and again in 2018. He plans to be there this year with his camera and tricorn hat.