Judy (and Eloise) in Greensboro

One week after performing in Greensboro, Judy Garland finally made it over the rainbow

By Billy Eye

“Kay is my best critic and severest friend.” — Judy Garland

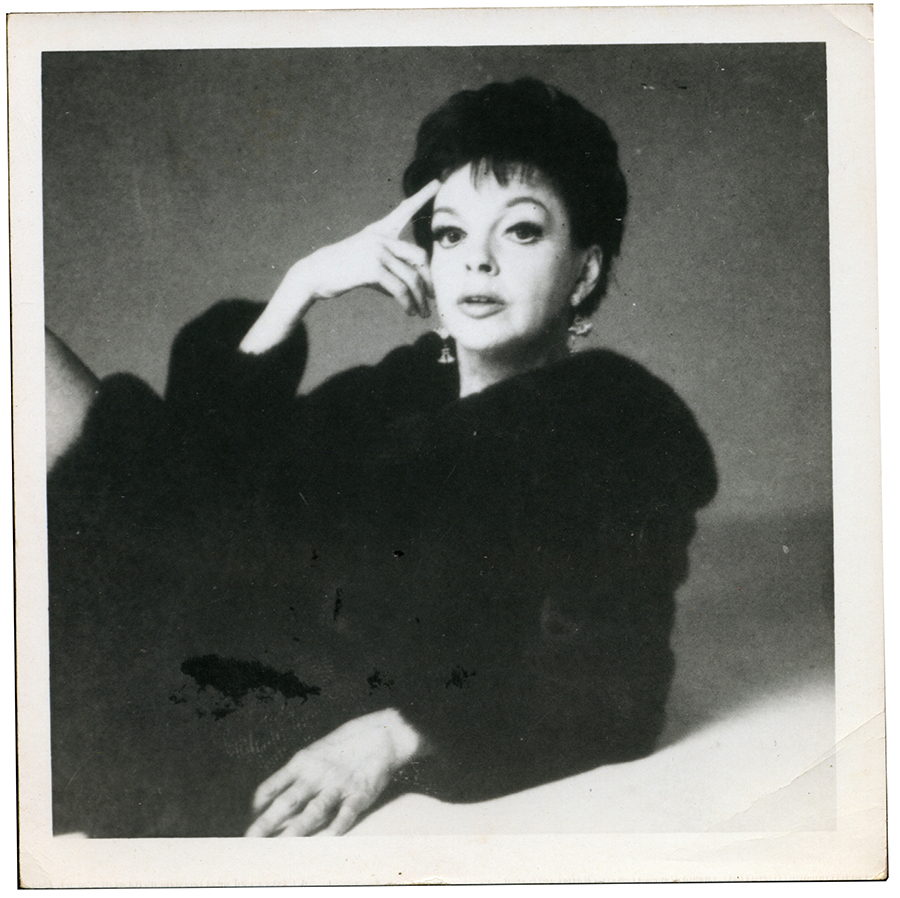

Bred to be an entertainer, like Tarzan raised by the Great Apes, hers was an almost impossibly insular existence. Frances Gumm, rechristened Judy Garland as a youngster, was a wholly manufactured product of a stage mother who pushed her relentlessly and a movie studio that wound her up chemically in the mornings then spun her down at night.

The biggest box office star on the MGM lot, she starred in 27 films in 14 years. In her 20s in 1950, as Garland began having difficulty coping emotionally (how could she not, under the circumstances?), the studio coldly spat her out into a world she knew nothing about. As a working professional earning millions for her bosses, she’d never attended a proper school, written a check, bought a train ticket, or negotiated a contract.

By the end of the ’50s, the 37-year old star was considered washed up in Hollywood, the nail in her professional coffin hammered shut after A Star Is Born flopped. Her albums were failing to chart and a lawsuit she was embroiled in with CBS kept her off television. Stricken with an inflamed liver, Garland was told by doctors she’d live the rest of her short life as a semi-invalid and never work again.

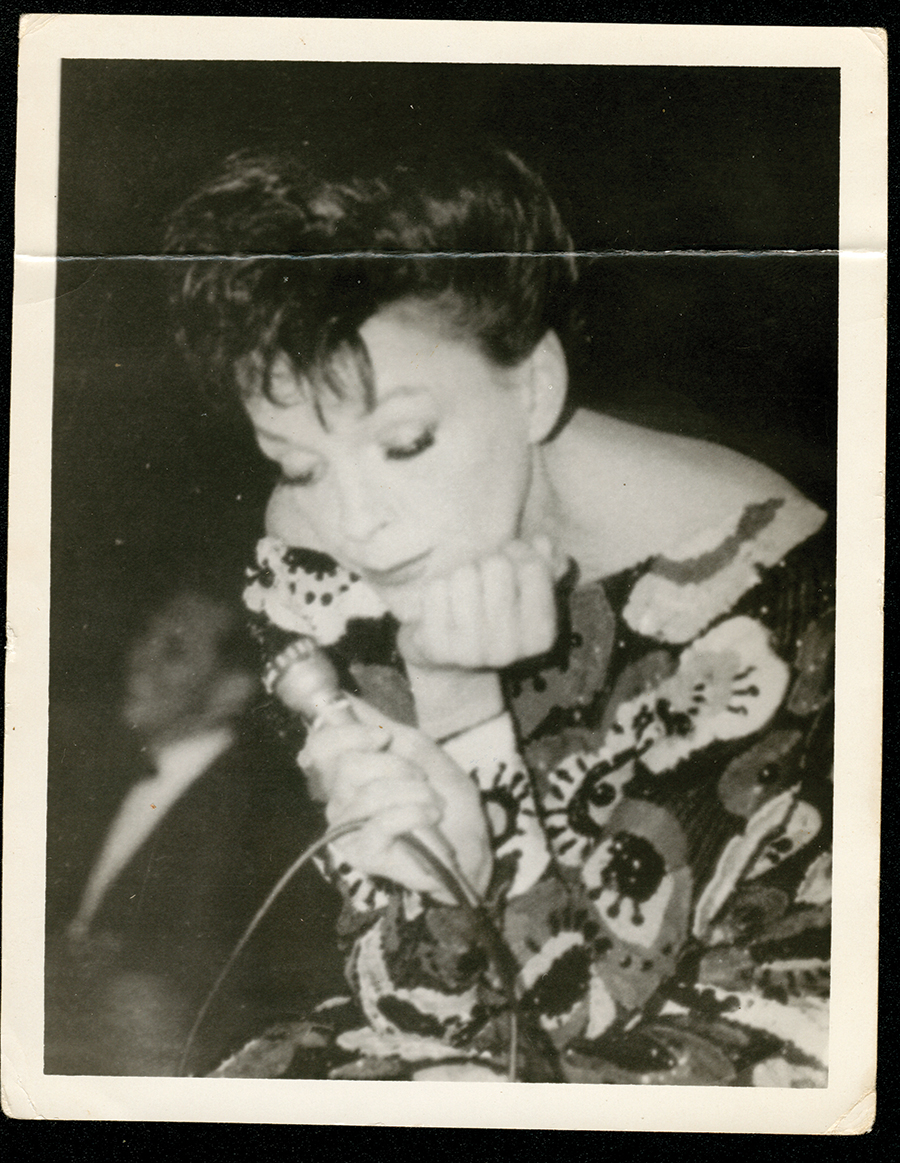

Yet she soldiered on. New managers got her out on the road in 1960 for what was billed as Garland’s “That’s Entertainment!” tour. No opening acts as in previous public appearances, just Garland fronting a 28-piece orchestra.

The singer would later declare 1961 to be the best year of her life.

In March of 1961, she paused that globe-spanning tour to shoot her emotionally raw scenes for Judgment At Nuremberg, for which she was nominated for an Academy Award. Afterward, back on the road, she headed down south for shows in Atlanta, Birmingham, Alabama, and Charlotte before arriving in Greensboro for the tour’s final performance on April 17, 1961.

Ticket prices ranged from $2 to a high of $3.75 ($17–$32 in today’s dollars, what a bargain). Some among the 2,400 ticket holders, it was reported by The Greensboro Daily News, were perturbed that the venue was switched at the last minute from the Coliseum to the smaller War Memorial Auditorium. This mix-up led to laughs when Garland sang her opening number lyrics, “If you feel deceived, don’t get peeved.” She joked that she too thought the show was in the main room, only discovering she was in the wrong place, “When I found myself alone!” But, because of the overflow, 240 lucky concertgoers got to watch from the orchestra pit.

Her throat was a bit hoarse that night but still vocally strong. The singer was somewhat plump but much trimmer than in past years when audiences gasped when she took the stage. Apologizing for her voice at one point, “I picked up a strange fungi in Atlanta,” she quipped as she popped what one reviewer called ‘a white lozenge’ (likely Ritalin) into her mouth, then reportedly carried on singing stronger than ever according to local press reports, an electrifying performance lasting 2 hours and 15 minutes.

For the first act “Little Miss Show Business” wore a tight black dress with a bright, hip-length jacket over tight sleek, black silk tights, switching to a multicolored beaded jacket over black slacks for act two. As she waved goodnight, hundreds of screaming fans rushed to the edge of the stage, arms outstretched, begging Judy to continue singing. She rewarded them by strutting back into the spotlight for two encores, “Somewhere Over the Rainbow” and “Swanee.”

Joining Garland in Greensboro that night was her closest confidant, Kay Thompson. In addition to being a groundbreaking nightclub performer, Thompson was somewhat of a movie star herself with a scene-stealing role in the musical Funny Face (“Think Pink!”). But she may be best known today as the author of Eloise, about that precocious, cosmopolitan preschooler reigning chaos down from “the room on the tippy-top floor” of the Plaza Hotel.

I recently reached out to Sam Irvin, author of the definitive biography Kay Thompson: From Funny Face to Eloise for insight into Thompson’s relationship with Judy Garland. “Most of all, Kay built up Judy’s confidence,” Sam tells me. “Judy felt relaxed and comfortable in Kay’s presence. Kay offered a reassuring smile of encouragement from the wings or from a prominent seat in the theater where Judy knew to look for her.” After all, he says, “Kay had been an extended family member ever since she began coaching Judy at MGM in the 1940s and had been named the godmother of Judy’s first-born, Liza [Minnelli], in 1946.”

In her live performances, Garland’s strike-a-pose delivery — stamping stilettos, one arm akimbo as the other scissors the air above her for those dramatic finishes — was pure Kay Thompson, who possessed an innate ability for dissecting a song, twisting it inside out, wringing out drama, pathos, hilarity and histrionics between the notes where no other performer had imagined they existed. Entertainers from Frank Sinatra to Andy Williams relied on Thompson’s singular musical arrangements to punch up their acts.

Kay Thompson could reimagine a cool jazz standard like “As Long As He Needs Me,” then transform it into a veritable “Battle Hymn of the Republic,” causing audiences to jump to their feet as if they’d lost control of their senses.

“Kay Thompson was Judy Garland’s eternal, beloved and well-worn security blanket,” Irvin continues. “Whenever Kay was with Judy on tour, they would rehearse and fine-tune the songs in her repertoire. Kay would give her pointers on how to stand, how to move, how to gesture, how long to hold a note — and when not to. Every detail was scrutinized under Kay’s magnifying gaze and Judy trusted her judgment and taste more than anyone in the world.”

While in The Gate City, the two entertainers undoubtedly dissected the concert that night in anticipation of Garland’s Carnegie Hall debut in one week’s time. Between the Greensboro gig and April 23rd opening night, Thompson retooled the act, choreographing Garland’s every move on stage.

Carnegie Hall changed everything, a musical achievement so unprecedented it’s often referred to as, “The greatest night in show business history,” most certainly the greatest comeback of all time.

Within months, the soundtrack album on Capitol leapt to No.1 on the Billboard pop chart, remaining there for 13 weeks, the first double LP to ever go gold. Judy at Carnegie Hall went on to win five Grammy Awards, including Album of the Year, Garland being the first female entertainer to do so.

Judy Garland was back on top, only this time, in contrast to her MGM days, living life on her own terms.

I’ll let Sam Irvin have the last word: “After Judy’s death in 1969, Kay took charge of Liza and encouraged her to step out of the formidable shadow of her mother and become a star in her own right, with an iconic style uniquely hers. Obviously, both Judy and Liza looked up to Kay and wanted to be like her,” Irvin says. “And Kay looked up to Judy and Liza, and wished she had their star-quality and vulnerability. They needed each other. It was a match made in heaven. Or “Pure Heaven,” as Kay would say whenever she heard or saw something that pleased her. It was a phrase that Judy yearned to earn from Kay — and she did. Often.” OH

Billy Eye would like to thank writer/producer/director Sam Irvin who took time from directing a motion picture to provide us with a peek into the lives of two show biz giants. His book, Kay Thompson: From Funny Face to Eloise, is a magnificent literary triumph. Irvin co-executive produced one of Eye’s very favorite motion pictures, Gods and Monsters.