And the ways it spreads

In a city shaped in part by the frontier Quaker families who established New Garden Meeting in the early 1750s, the concept of a sustaining “Inner Light” has long informed the spiritual life of Guilford County.

The idea of an “inward light” or the “light of God found in every human being,” is central to Quaker doctrine, derived from numerous Biblical passages including the Gospel of John (8:12), which quotes Jesus of Nazareth explaining to his followers: “I am the light of the world. Whoever follows me will never walk in darkness, but will have the light of life.”

Poets and sages from every spiritual tradition have articulated some version of a divine inner light that motivates one neighbor to befriend and help another. “Just as a painter needs light in order to put the finishing touches to his picture,” Leo Tolstoy wrote in his memoir of faith, “so I need an inner light, which I feel I never have enough of in the autumn.”

This autumn, as we gather round a table resplendent with the harvest of our labors, we think this to be the perfect moment to “illuminate” eight stories of local people and organizations whose quiet determination to help others in need sustains their lives and serves as a model of true friendship to us all. Most operate well beneath the public radar, grown from the grassroots of someone else’s keen personal need, living proof that there is a light within us all.

And all we need to do is let it shine.— Jim Dodson

Gathering Together

Mary Lacklen’s Community Tables feeds body and soul during the holidays

By Nancy Oakley • photograph by Amy Freeman

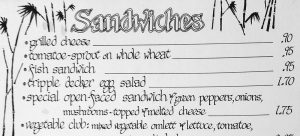

Early on Thanksgiving morning they’ll arrive at the Greensboro Coliseum: The couple who’ve pitched in every year for for twenty-five years. Ted Hoffler, wielding “Excalibur,” his electric carving knife, will lead teams of carvers slicing into 1,500 pounds of boneless turkey breast along with 2,500 pounds of mashed potatoes, both cooked ahead of time at Victory Junction’s kitchens in Randleman. Others will slice 450 pumpkin pies. Legions more working in shifts — giddy high school students, church and civic groups — will fill Styrofoam clamshells with the turkey and mashed potatoes. The containers will be filled with other sides — green beans cooked in ham hocks, gravy, stuffing from the Painted Plate, cranberry sauce, sweet potato casserole and rolls. Counters will apportion the boxes to tables, before they are bagged two at a time with two cartons of milk. Yet more volunteers from Triad Health Project, Senior Services, Delancey Street and local churches will retrieve the meals and deliver them to recipients of the agencies’ services. One year, a ponytailed fellow made deliveries to homeless denizens of the woods and bridges.

Amid the hustle and bustle will be Mary Lacklen, coordinating this massive effort known as Community Tables’ Thanksgiving Day Feast, which feeds nearly 5,000 people in need.

“I feel like I’m a drill sergeant,” quips the director of operations for Libby Hill and one of the founders of Bert’s Seafood. “But you want people to have fun. You want to engage people, because somebody has to take my place eventually.” Whoever assumes Lacklen’s mantle will have a tough act to follow. A tireless community servant who also devotes time to Triad Local First and Share the Harvest, she has been a driving force behind Community Tables since its inception thirty years ago as an annual project of the now-defunct Guilford County Restaurant Association back when Lacklen served as its president. “We worked with Ham’s the first year,” she says, explaining that the meal was patterned after the annual Christmas dinner for the needy started by Ham’s proprietor Marc Freiburg. (His daughter, Anna, who runs Bender’s Tavern, has continued the tradition; for the last six years she has partnered with Lacklen, sharing funds through Community Foundation of Greater Greensboro and feeding another 5,000 people annually). “We did it outside [at the Salvation Army] on the big pig cookers. Sat up all night long,” Lacklen recalls of the initial endeavor that fed 300 people.

“We” included the other guiding spirit behind Community Tables, the late Ken Conrad, former owner of Libby Hill, and Lacklen’s mentor and friend who died from pancreatic cancer just weeks after last year’s Thanksgiving meal. “I still save all my texts back and forth. I sent him pictures during the course of the day,” Lacklen remembers. She has since established the Conrad Endowment through the Foundation.

The two kept the annual Thanksgiving feast going, moving first to the Greensboro Urban Ministry and then four years ago to the Coliseum. For the last five, churches have come aboard. One of them, United Congregational Church, hosts a buffet-style meal, replete with tablecloths, fresh flowers, live music, and a table of desserts and fruit, courtesy of the Fresh Market. “People come dressed in their Sunday best,” Lacklen says, some homeless, some barely getting by, some elderly and alone, some of them college students with no place to go on the holiday. From 10:30 a.m. to 2 p.m. they’ll arrive at the church on Radiance Drive by bus, thanks to volunteer Matt Logan, and will be greeted with a cup of hot cider in the lobby. “I want people to feel warm and welcome,” Lacklen says. “That was the intent.”

All told, Community Tables has fed about 100,000 people in its thirty years, and each year costs rise, because, as Lacklen observes, “more and more people need food.” (It takes $25,000 and change to fund the operations for the Thanksgiving meal and the Christmas dinner at Bender’s Tavern). Lacklen is quick to point out that support comes from individuals, and all of it goes directly to the meals. “There are no administrative fees. It’s very grassroots-driven,” she says, adding, “I’m proud of Greensboro.”

And at the end of an arduous day, after seeing so many old friends and the faces of people sated from a meal, Lacklen admits she succumbs to the emotion — and exhaustion — of the occasion. “I always cry the whole way home when I’m done,” she says. “I always try not to, but I always seem to.” OH

To donate to the operations of Community Tables, go to cfgg.org and under the “give” tab, select “contribute online” and choose Thanksgiving/Holiday Fund in the dropdown menu, or mail a check, designated for the Thanksgiving/Holiday Fund to: CFGG, 330 South Greene Street, No. 100, Greensboro, NC 27401. Additionally, donations can be made to the Conrad Endowment, which has its own field in the dropdown menu.

To volunteer: Go to Community Tables’ Facebook Page, www.facebook.com/CommunityTables

Neighbors Helping Neighbors

Barnabas Network refurbishes household goods and lives

By Jim Dodson • photographs by Sam Froelich

“In essence,” says Erin Stratford Owens, executive director of the Barnabas Network, “we are simply an example of neighbors helping neighbors achieve something so important in life — a home with proper furnishings, the basics that will let them make a better life for themselves and their families.”

It’s opening time, a little after 8 a.m. on a chill and misty morning in late autumn, and already potential clients of the nonprofit organization that provides donated furniture and household items to families and individuals in transition have already begun to gather outside the organization’s 26,000-square-foot facility on 16th Street, the former battery and tire center of the late Montgomery Ward store that previously occupied the site.

Formed in late 2005 by a group of concerned parishioners at Holy Trinity Episcopal Church and quickly joined by other Gate City residents who shared the view that a key to rebuilding lives is having the stability of a decently furnished apartment or house, Barnabas last year has served more than 1,000 households and 3,000 individuals.

In the spirit of Saint Barnabas, described in the Acts of the Apostles as Saint Paul’s missionary traveling partner who brought Christianity to the Hellenic world of gentiles in A.D. 59, the staff of two full-time and seven part-time employees operates on a budget of roughly $400,000 a year and relies on a network of 170 different coordinated local social service agencies to screen and refer a broad section of clients, including many who were formerly homeless or disabled. Upon the proper screening and assessment of a family or individual’s household needs, the household basics — everything from refrigerators to dishes, dining room tables to teapots — are matched to the client’s specific needs. The organization’s motto is “Recycling Furniture, Restoring Lives.”

“Barnabas was known as the Son of Encouragement — and that’s the spirit in which we operate,” says Owens, who left a successful news service career in New York to enter the nonprofit world, joining Barnabas seven years ago. “Most of us can’t imagine what it’s like not to have a decent bed to sleep in or a home that is comfortable and secure, a place to begin the process of rebuilding a life. A table, a plate, even a set of chairs can change a life,” he says. Many of Barnabas’ clients come from rehab or are fleeing domestic violence: “The stories are as diverse as they are heartbreaking — and are starting over with little or nothing. Furniture is expensive.” Owens says that by providing good recycled furniture and household necessities, Barnabas hopes families “take the next steps to provide for their families and take care of themselves. Good home furnishings keep families together.”

The angels of the Barnabas Network are everywhere in the Gate City, Owens adds, manifest in the volunteer efforts of more than 100 volunteers and hundreds of residents who donate furniture and every household item imaginable on a regular basis. Tuesdays through Saturdays, staff members pick up donated items and deliver them to an average of six client households per day on Tuesdays through Fridays.

Then there are folks like George Rettie, who came aboard on the heels of a 30-plus-year career at Guilford Building Supply. From a woodshop full of donated supplies that rivals his former domain, Rettie repairs, restores and even builds custom pieces for clients. “For me,” he says, “this is simply great karma — using my God-given skills to help others get back into life. I love bringing furniture back to life. That’s what this place does for people.”

“And the blessings keep coming,” says Erin Owens. Supported by a recent fundraising campaign chaired up by Greensboro philanthropist Bobby Long and wife Kathryn, Barnabas will soon move to a permanent home at 838 Winston Street, a gift from Mary Hart Orr and Katie Rose, daughters of the late John Ellison. The building formerly housed machinery that served the textile industry.

“The new building is roughly half the size of our current one,” notes Owens, “but the way it is set up will enable us to process goods even quicker and serve many more people. This year we helped secure more than 1,000 families. Next year we’re aiming for 1,300. It’s true neighbor helping neighbor.” OH

For more information (336) 370-4002 or visit Info@thebarnabasnetwork.org

The Art of Healing

The medicinal value of arts and gardens at the Cone Health Cancer Center

By Cynthia Adams

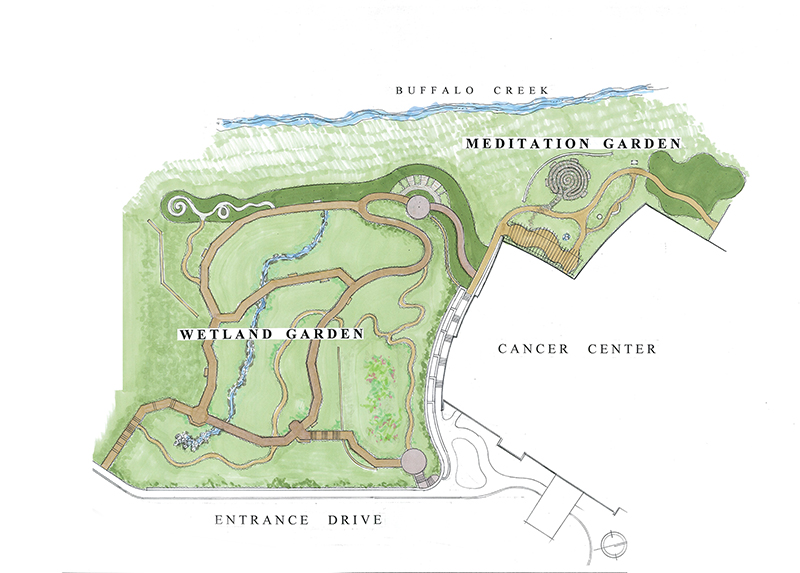

A landscape artist and a philanthropist stand in a former eyesore in the autumn sun at the Cancer Center at Wesley Long Hospital. The last time I was here was with my mother, a breast cancer patient at the Cancer Center. (Breast cancer brings the largest number of patients to the facility.) The wetlands abutting Buffalo Creek were once hidden by a concrete wall on purpose — they were an afterthought, scruffy and forgotten.

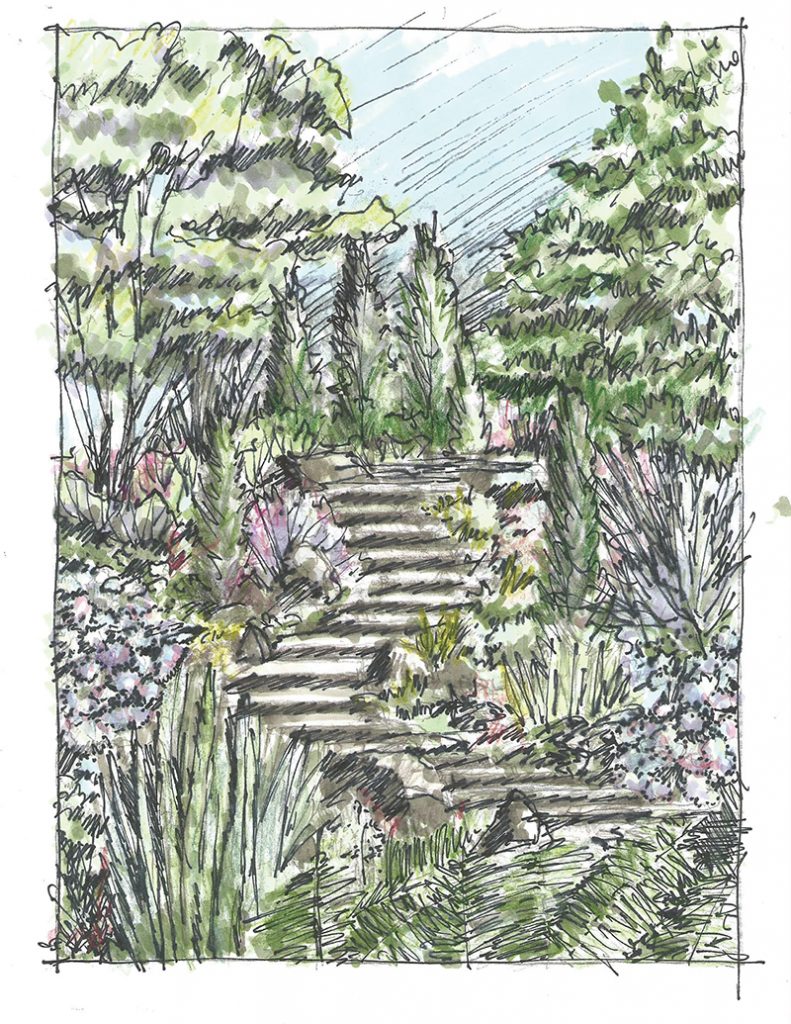

Sally Pagliai, landscape architect, and Pam Barrett, senior philanthropy officer for Cone Health, talk in a rush about the transformation of a forlorn place into a biodiverse healing garden.

Getting out into nature and onto the rambling paths of the garden helps patients and families cope with the stress of catastrophic illness. Beforehand, families of patients were resigned to the lobby’s stiff-backed chairs and dog-eared magazines as they waited for their loved ones to endure radiation or chemotherapy. In 2006, Pagliai’s husband was treated here when he developed cancer. After his death, a phlebotomist sent her a message. What did she think about designing a healing garden?

The lanky California transplant knew what she thought. She wanted to do it. Pagliai created beautiful renderings. Like many others who enlisted, she worked for free. Administrators were eager to help. “One kind soul donated $10,000 to kick start it,” Barrett says. “We did $30,000 worth of work with it,” Paglia adds.

The ideas rooted and sent up shoots. A nursery owner donated trees. Volunteers helped plant one hundred of them. Foundations and individuals donated planting beds. “The community stepped up,” Barrett says, “and we have nearly met the $1.3 million goal.” The garden opened in June of 2015. There are spaces for rest, reflection. Walkways provide easy (wheelchair-friendly) access to overlooks, patios and benches. There are balconies and patios for cancer patients.

Families donated meaningful plants, such as hellebores, from loved one’s gardens. Somebody provided a gardening shed and supplies. “Gloves, clippers, loppers,” says Pagliai. Twenty-five volunteer gardeners queued up to help keep the pathways. “We were here yesterday, weeding.”

A Japanese maple garden, arbor and new labyrinth are to come. A meditation garden will be constructed near the chemotherapy and radiation treatment areas.

The city, both women say, was incredibly supportive. They helped restore Buffalo Creek’s far bank, removing fallen trees and shoring up the other side. The creek is now a rippling ribbon through the wetland garden.

Indoors, there is a second aspect, Healing Arts. Now families can noodle, doodle, color, paint and draw as they wait for patients. Hallways are hung with permanent and temporary artworks. (A photo exhibition is currently on display.)

The program’s reach is almost frightening: In 2014 alone, 69,000 cancer patient visits occurred, and 127,000 visited the adjacent Wesley Long and Emergency Room. There are 1,475 employees. Then there are the many caregivers, themselves in need of the healing art and green space . . . a riparian scene that is as beautiful as Paglia’s renderings promised. OH

To donate: ConeHealth.com/HealingGardens

To volunteer: (336) 832-9450.

Royal Flush

Hands For Hearts started as a gamble — and beat the odds

By Nancy Oakley • photographs by Amy Freeman

“His smile was sparkling,” says Kathleen Little of her son, Matthew Sullivan. “He loved people and people loved him.” Skotty Wannamaker, a friend of her son’s, agrees. “Matthew was one of those guys who probably had twenty best friends, and I was one of those,” he says. The two met when Wannamaker, a new kid at Page High School, was shooting hoops the second day of school, “and formed a bond immediately,” Wannamaker recalls. One that lasted twenty years — through college, marriage, careers. “Matthew had a heart that went for days,” he adds, reflecting on the friend who would drop whatever he was doing to assist or simply be with his pals. “I don’t know when he slept.”

And Sullivan had a similarly tight bond with his 2 1/2-year-old nephew, Nicholas LaRose. Born with a multiple heart defects — a missing pulmonary artery and a large hole in his heart — Nicholas was in and out of the hospital in his hometown of Charleston, South Carolina, Little says. “Matthew was there for the first open-heart surgery, and just adored him.”

But Matthew Sullivan would leave an irreparable hole in everyone’s hearts and lives in January of 2014. Rounding a curve on his Kawasaki ZX-10R (or Ninja), he went off-road; perhaps because the motorcycle’s kickstand engaged when it shouldn’t have, the 34-year-old was catapulted into mid-air and into a “massive church sign,” says Little. Wannamaker and another close friend, Jeff Fusaiotti, among others couldn’t accept that their friend was gone. “The only thing we felt we could do,” says Wannamaker, “was to keep him alive by helping kids like Nicholas.”

Where to begin?

Through Nicholas’ mom Nicole LaRose, an occupational therapist at University Medical College of South Carolina, Wannamaker and Fusaiotti started chatting with top surgeons. Fusaiotti also suggested talking with a neighbor, Dr. Greg Fleming, a pediatric cardiologist who worked at Duke Children’s Specialty Services in Greensboro. The same Dr. Fleming had treated Wannamaker’s daughter, Charlotte, who had been born with a heart murmur. The three had a dinner meeting. Then came more meetings with professionals from Duke. “We understood about 15 percent of what they were telling us,” says Wannamaker, a wealth advisor for DHG in High Point.

“But the parts we understood were mind-blowing,” he says. Such as: Congenital heart defects (CHDs) are the No. 1 birth defect in the United States and the world. They can range from a hole in the heart that ultimately closes (as Charlotte Wannamaker’s did), or they can be more severe, such as the multiple defects that Nicholas suffers from. And most are difficult to detect, whether they occur in utero or shortly after birth, sometimes a day or two later. But the encouraging tidbit Matthew Sullivan’s friends learned was that “in the last ten years the mortality rate of CHD kids has decreased 30 percent,” Skotty Wannamaker says. “So the research of the last ten years has trumped the research of the last forty.”

Through another connection of Fusaiotti’s the two discovered Children’s Heart Foundation, a national organization that approves and funds research on CHDs. It was just the vehicle they were seeking for their fledgling nonprofit, Hands For Hearts. The Foundation serves as a “matchmaker,” to use Wannamaker’s term: It approves research projects, which can cover everything from valves to catheters. It also funds studies on conditions such as ADHD, that sometimes accompany CHDs. Hands For Hearts chooses which of the grants to support. Operating as an independent 501(c) (3) with no overhead, Wannamaker says, “We know the scientists, we know the project, we know the timetable, we get updated results. We become a part of the process.”

But Hands For Hearts also has a mission to enhance the lives of local children with CHDs. This summer, the organization partnered with Camp Weaver to do a test-run sending kids to camp. “So 10-year old little girls or boys who have scars running down their chests and worry when they get out of breath have the ability to have an experience in a safe environment with medical professionals where they get to meet other kids just like them,” Wannamaker explains.

To raise the money, Wannamaker, Fusaiotti and Little came up with the idea of a Casino Night held on the last Saturday in February at Greensboro Country Club. The reason? “Matthew loved to gamble,” says Wannamaker, adding, “But he was the worst gambler! I think what he loved more than the gambling, was the camaraderie that came from it.” The event seeks to create the same, with prizes as stakes rather than money, and a King and Queen of Hearts: two local children with CHDs coronated as the charity’s reigning monarchs for a year. Wannamaker credits Little with organizing, spreading the word. “She’s our rock star,” he says, pointing to a recent concert at her home for Hands For Hearts sponsors. He also credits the generosity of the community for stepping up: In just two years Hands For Hearts has raised over $200,000.

As for Little, “I’m just so amazed at what they’ve done,” she says of Matthew’s friends. “They’re two young guys with children and professions who have poured their heart and soul into this,” she says. “They’re such a gift to our family.”

Nicholas, she says, is doing well after surgery in July — possibly his last for another ten years. And Little has started her own healing process, facilitating groups of bereft parents at Beacon Place, and learning Healing Touch, a holistic approach to medicine that is gaining wider acceptance. “Matthew has sent me people,” she says of her overwhelmingly gratifying interactions with the bereaved and the afflicted.

A truly winning hand for the gambler with the lion’s heart. OH

For information on Hands for Hearts go to handsforhearts.org.

Sustainably Happy

Whitsett’s Peacehaven Farm lives up to its name for

adults with disabilities and for their families

By Annie Ferguson • photographs by Lynn Donovan

Jeff Piegari had just finished a yoga session when asked what he liked about living at Peacehaven Farm. “It’s calm,” he replied.

Piegari lives with three other adults who have disabilities (aka core members), along with three resident assistants and a golden retriever named Maverick. The sustainable, 89-acre farm in Whitsett is a place where people of all abilities live and work together. Modeled after the well-known L’Arche Communities, Peacehaven was founded in 2007 by Tim and Susan Elliott along with Buck and Cathy Cochran, two couples familiar with the challenges of raising children with disabilities, who wanted to see their offspring have meaningful adult lives as well.

“I’ve always been open to learning about the challenges and struggles for individuals with disabilities and their families,” says Buck Cochran, Peacehaven’s executive director, a United States Navy veteran and a former associate pastor of Westminster Presbyterian Church in Greensboro. “As a pastor I saw in a larger way how individuals and families can struggle. Their lives can be so isolated. I was interested in finding support — to increase their connection with the larger community, with housing and vocational training, and opportunities to be with people.”

The Elliotts had been his parishioners when they approached him about starting Peacehaven. After the land for it was cleared, construction started on the first group home in 2012, thanks to help from partner Habitat for Humanity of Greensboro. Sadly, Susan Elliott lost her battle with cancer three years prior, but in 2014, her legacy blossomed when the first group home, called Susan’s View, opened.

“We modeled it after L’Arche Communities, which have been around for more than sixty years. The closest one to us is in Washington D.C.,” Cochran explains. “The idea is that people with disabilities are teachers, too, and that we can help them develop their talents becoming everything they’re created to be.” Plans for additional homes and a community center are in the works with the aim of housing thirty adults with disabilities. Right now the farm has a tremendous need for housing, so Cochran and other staff are doggedly pursuing funding.

In 2015, more than 1,000 people of all ages volunteered at the farm, and many have become regulars. Volunteers come out for Saturday work days, tending to various outdoor projects including the plants — tomatoes, cucumbers, watermelon, peppers, asparagus, sweet potatoes, blueberries and more — all grown sustainably with no chemicals and an eye on water and energy conservation and sustenance for the residents and the community.

Cochran says the biggest surprise in running Peacehaven has been the number of college students who give of their spare time. Nearby Elon University is one school that has been a major support network. “The first couple of years I drove the college students crazy asking why they’re here,” he says. “It’s a generational thing, these folks are really interested in the community and how they can connect what they’re learning in school with real-life stuff.”

Volunteers also offer classes in which residents learn to create. One of the most popular is the fiber arts class using sheep’s wool. “It’s an activity that everyone can find something to be a part of regardless of disability,” Cochran says. “The stuff they make is awesome — a nativity set, soap with felted covers, dryer balls and more.”

Developing talents, relationships and community is the lifeblood of the farm, and Cochran likens it to the area’s Quaker roots. “Quakers have this notion of letting your life speak, and I like to think that we’re doing that as an organization,” he says, “letting the life of the organization speak to the community about important things.” OH

For more information on Peacehaven Farm, go to peacehavenfarm.org.

On the Road Again

How Wheels4Hope transformed a family’s life

By Maria Johnson • Photographs by Charles Hartis

Here’s what Kasie Hunt’s mornings looked like before she had a car.

She woke up at 6 a.m.

She got her three sons ready for school.

She got herself ready for work.

She hustled the two older boys to their elementary school bus stop by 7:10 a.m.

She ushered her youngest son to his preschool bus stop by 7:45 a.m.

Then, depending on the job and the shift she was working, Kasie, who did not own a car, negotiated a patchwork of transportation.

Sometimes, she caught a city bus that took her downtown, where she transferred to another bus. A one-way trip to work usually ate up an hour-and-a-half.

Other times, Kasie caught a ride with someone who had a car.

“My mom, friends, family, taxis — whoever’s schedule permitted them to help me, and sometimes no one could,” she says.

On Sundays, Kasie and the boys relied on a friend for a ride to church.

There were no spontaneous trips.

The boys had no after-school activities.

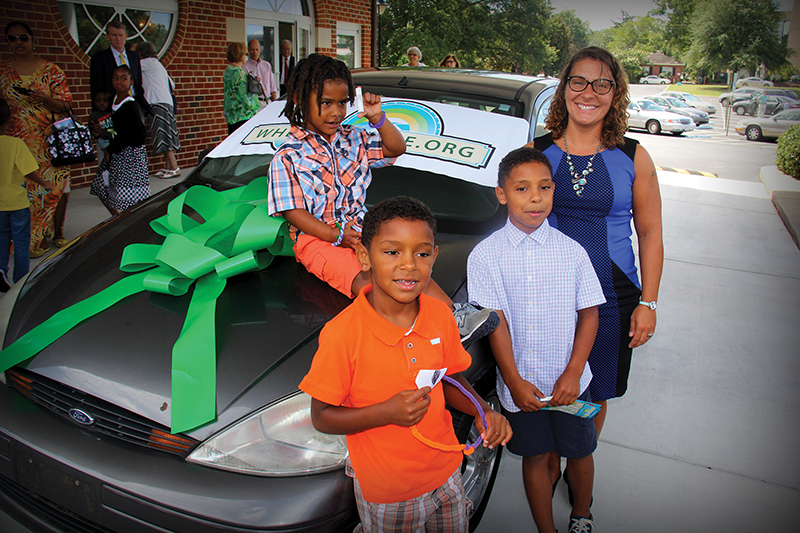

All of that changed in August, when Wheels4Hope made Kasie independently mobile again.

Wheels4Hope is a nonprofit organization that pairs donated cars with people who qualify. Founded in Raleigh in 2000, W4H opened an office and garage in Greensboro in 2012. There’s another location in Asheville.

The Greensboro hub, at 4006 Burlington Road, has matched more than 130 cars with drivers who were referred by local agencies that help people become self-sufficient.

Kasie’s referral came from Partnership Village, a Greensboro Urban Ministry community for formerly homeless people. Kasie has lived there with her sons for the last year-and-a-half. She got sober more than two years ago and started rebuilding her life.

She worked in a school cafeteria for a while. Then, she regained her status as a licensed practical nurse — a privilege that she gave up voluntarily when addiction overwhelmed her — and she started working at a rehabilitation center.

She earned her driver’s license back. The next step was to get a reliable car.

A friend told her about Wheels4Hope.

Like all W4H car recipients, Kasie had to meet several conditions, including the ability to pay $500, plus title and transfer fees, and to show proof of insurance.

Kasie explained, on her W4H application, what having a car would mean to her.

“I think I wrote a page and a half,” she says.

She received her vehicle at a “car blessing” at First Baptist Church in Greensboro.

“Oh man, it was really a good feeling,” she says. “You should have seen the smile on my face.”

Now, she scoots around town in a dark green 2002 Ford Focus. It’s nothing fancy, but it’s a game-changer for Kasie and her family.

“I don’t know anything about the person who gave the car, but you can tell they took really good care of it,” Kasie says.

Her boys play football in after-school leagues now. They go to the public library. And the Greensboro Children’s Museum. And the PlayPlace at McDonald’s.

“It’s such a good feeling, not to be a burden on someone and to be able to do things for my kids,” says 29-year-old Kasie. “It’s easy to take things for granted, you know?”

People who donate cars to W4H can feel good, too.

When their cars go to people who have been referred by W4H’s partner agencies, donors can claim a tax credit equal to the car’s fair market value, typically between $2,000 and $4,000.

W4H sells the more valuable donated cars on its retail lot. In those cases, donors can claim tax credits equal to the sale prices of the vehicles.

Cars that cannot be driven or that need extensive repair are sold to dealers. Donors can claim at least a $500 tax credit, more if their car sells for over $500.

W4H plows the revenue back into the goal of getting dependable cars to struggling families.

“It’s wonderful to see how excited the recipients are when they receive the keys to their vehicle and a new life,” says W4H spokeswoman Deborah Bryant. OH

Learn more about Wheels4Hope at wheels4hope.org. The Greensboro office number is (336) 355-9130.

How Their Garden Grows

With faith, hope, love and hundreds of Out of the Garden Project volunteers

all in a (proverbial) row, Don and Kristy Milholin feed the hungry

By Annie Ferguson • photographs by Lynn Donovan

The year 2009 was a tough one for Don and Kristy Milholin. Like so many others, Kristy, a hairstylist, and Don, a church music director, were feeling the crunch of the Great Recession. “But there were people who had it worse,” says Kristy. Therein lay the couple’s mindset and thus the impetus for Out of the Garden Project, the largest organization whose mission is combating childhood hunger in Guilford County. “We learned of six families at Morehead Elementary who needed extra food, so we started packing food for them around our small dining room table,” Kristy explains. “Two or three years before, I kept telling my husband that I felt this aching. I knew I needed to do something, and I didn’t know what it was.”

It turns out the couple found that something and then some. With the help of volunteers, their operation quickly grew. When people started donating money, the Milholins filed for a 501(c)(3) nonprofit organization. “It takes longer than you’d expect,” says Don, the organization’s executive director. “I took a nonprofit management course at Duke, and there I learned it takes about ninety hours to get everything in order.”

The time-intensive effort has paid dividends by way of the sheer number of meals the project now provides hungry children and their families. Through its various programs operating from a donated warehouse space at C3 Greensboro, Out of the Garden Project yields 100,000 meals a month with the help of 800 volunteers, and by the end of this year it will reach its 5 millionth meal.

“It’s the community that’s built around our tables that’s changing the world, not just a bag of food,” Don says. “One friend comes in, and I always thank him. He says, ‘You know Don, I’m not doing this for you.’ He’s there because he has the feeling that he needs to do something. They all have that heart.”

The fresh food program gets to the heart of Kristy’s calling to feed the hungry. “Fresh Mobile Markets — now our biggest program — sends trucks go out to twenty-two different locations.” Some of them are food deserts, neighborhoods where there’s a shortage of grocery stores for those without cars. Other locations target those who simply don’t have the money to buy groceries. “We include donated produce, meat products, pizza and breads,” Kristy explains. “I find comfort knowing the children don’t have to worry if they’re going to have a meal or not tonight,” says Kristy.

For Kristy, the seed was planted long ago: “Growing up, there was a time when my three siblings and I only had rice and gravy to eat. When my mom landed a better job, we could finally go to the store and pick out what we wanted. I remember getting a cantaloupe. We hadn’t had one in such a long time. When something like this happens to you, you empathize when you get older.”

Don and Kristy host summer camps and started a food reclamation program that saves leftover food from school cafeterias to give to families in need. “Don’s been the innovative thinker in getting food out to children in these unorthodox ways,” Kristy says.

Don explains, “My brain doesn’t function on a linear line. When we see a need and when we think how we can fill a need, often the world thinks of why we shouldn’t do that.” Then the Milholins show everyone why they should. OH

For more information about Out of the Garden Project and its programs, or how to donate time and money, visit outofthegardenproject.org.

Editor’s note: Out of the Garden was recently selected as a partner with the City of Greensboro, awarded a $470,000 Local Food Program Implementation grant from the federal government.

Leveling the Playing Field

How Sari Rose uses soccer to teach the disadvantaged life skills

By Ross Howell Jr. • photographs by Amy Freeman

“The reason I left collegiate soccer may sound cheesy,” says

Sari Rose, director of the Greensboro United Soccer Foundation (GUSF). “I played at Wake Forest, then coached. But with double majors — politics and religion — I found myself wanting to work with kids in need.”

The first step was graduate study at UNCG. There, Rose met Thomas Martinek, a professor in the School of Health and Human Sciences. Martinek coordinates graduate pedagogy in the Kinesiology Department and oversees the Community Youth Sports Development program.

“I helped Dr. Martinek run Project Effort and the Youth Leaders Corps [YLC],” Rose says. “Project Effort is an after-school program for elementary and middle school students using physical activity to promote personal and social responsibility. YLC is for high school students.”

“As I was finishing my studies,” she continues, “I approached Pete Polonsky, executive director of the Greensboro United Soccer Association (GUSA), about my idea for a nonprofit. I wanted to work with kids in physical activity and youth leadership from elementary school all the way through high school. Often high school kids have after-school jobs, so the usual activities schedule is out. They can get lost.”

With coaches already working in the community, Polonsky asked Rose if she’d consider running her program through GUSA’s foundation. “What’s funny is that I’d always said my ideal job would be directing a nonprofit using sport to impact the lives of kids and the community in positive ways. Pete was offering me my dream!” Rose recalls.

“Some of the kids in our program are great athletes and some aren’t. So we talk about life skills, success skills. Say we’ll do a drill to improve dribbling and passing. Then we’ll ask, ‘OK, what if you worked that hard on your math at school?’”

The program also offers paid referee positions to kids who need incomes. “We get kids to think about sport as a way to earn income, whether as a referee or coach. We also help them get on track for community college or college, since some of our practice venues are campuses.”

But for many children in need, transportation is a problem. Rose’s solution? “We found a 30-year-old church bus in Hendersonville and raised money to purchase it. An individual donated new tires. So now we drive kids to events in this neon-green bus with purple wheels. They love it!” She smiles. “Well, not everybody is crazy about the purple rims.”

Currently the (GUSF) runs weekly programs in six different schools and the Boys and Girls Club. There is a Saturday Soccer program at Presbyterian Church of the Cross, where Guilford County Police Department officers work with the children.

This past summer, in addition to a Boys and Girls Club camp and a Soccer Nights camp with Cross Fellowship Church, GUSF offered a free soccer camp for refugee children.

“People in the community were incredibly generous,” Rose says, “with food, clothing, hygiene items, shoes, jerseys, caps, gear. Coaches from all over North Carolina donated their time. The kids were so appreciative. Those gruff coaches would be running drills, next thing you know, they’re hugging the kids, encouraging them.” OH

To learn more about Greensboro United Soccer Foundation, go to

gusafoundation.org.

1 Comment

[…] https://ohenrymag.com/the-light-within-us/ […]

Comments are closed for this article!