Elvis Presley’s love affair with the Gate City

By Billy Ingram

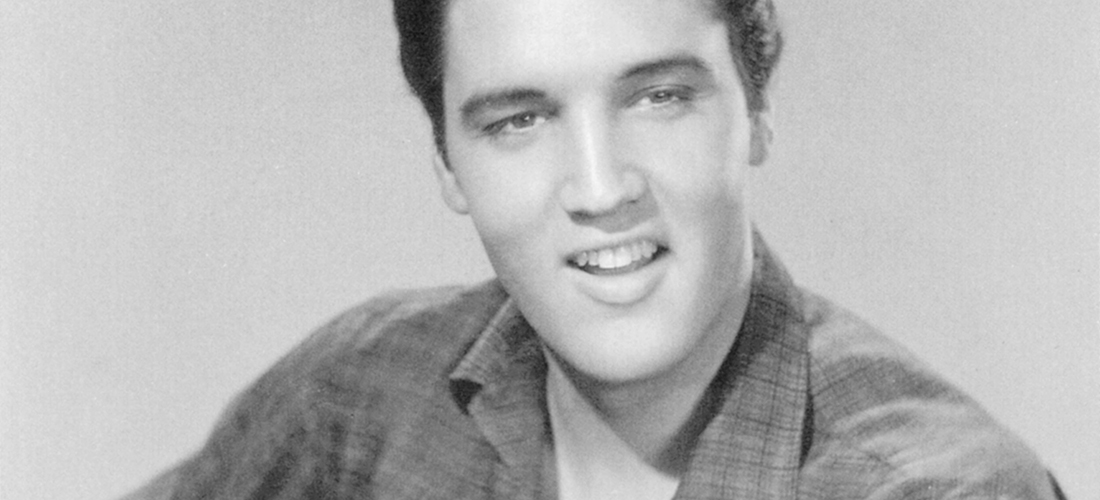

Elvis Aaron Presley sold more records than any other solo artist in history, a quarter billion at the time of his death at age 42. When “Burning Love” was released as a single on August 1, 1972, it became his fortieth and last Top Ten hit, one he sang on stage for the first time four months earlier at the Greensboro Coliseum before a sold out crowd that screamed and wailed at his every sideways glance. The tune was so unfamiliar Elvis had to read the lyrics from a sheet, a scene captured by a film crew embedded with the band who were shooting what would be the King of Rock ’n’ Roll’s thirty-third and final motion picture, Elvis on Tour.

No other recording star has had a more enduring relationship with our city than Elvis, which is why his flirtations with Greensboro will remain forever pressed between the pages of our minds, sweetened through the ages just like wine.

The first time Elvis was heard on the radio, in July of 1954, the Memphis station was inundated with phone calls and telegrams (expensive, but that was how you tweeted in the ’50s). The response was so overwhelming, the deejay played that acetate seven times in a row, then called Elvis’ mom and had her retrieve the shy 19-year-old from a movie theater to rush him down to the station for an interview.

Elvis the mama’s boy (never an insult down South) didn’t drink or smoke, was demure and unassuming, but flung himself into performances with an unnerving intensity accented by quivering lips, unnaturally dark eyes and a slicked up, black ducktail pompadour. His ’do took three kinds of grease and considerable time to prep so that it curled and flopped as he threw his head forward to sing. Teen girls squealed and swooned uncontrollably at his pelvic gyrations and raw sex appeal, and before long, riots were breaking out with young women mobbing the singer, tearing his clothes off in a feeding frenzy.

And so it was that in the spring of 1955, Elvis and his rough-hewn combo played their first dates in North Carolina, first at the New Bern Shrine Auditorium and then in Asheville’s City Auditorium, followed by September dates in those towns, augmented with stops in Raleigh, Wilson and, closer to the Gate City, the Thomasville High School Auditorium.

Then, on Monday, February 6, 1956, Greensboro welcomed the up-and-coming pop star for two matinee and two evening performances at the ornately elegant National Theater at 311 South Elm. Elvis had driven into town the night before in his pink 1955 Cadillac Fleetwood just as his first single on RCA Records “Heartbreak Hotel” began climbing the charts on the way to the No. 1 spot. Suddenly, it was his name that would be featured most prominently in advertisements and on the marquee, above more established acts like The Louvin Brothers and the Carter Sisters. George Perry and Jim Tucker, seen as The Old Rebel and Pecos Pete on WFMY-TV, ventured backstage at the National to meet the Carters when a bashful Elvis walked over to introduce himself.

Elvis left touring behind soon after in favor of cranking out lightweight Hollywood musicals, as many as three a year. No other movie star was pulling down a million dollars a picture on an ongoing basis, his happy-go-lucky cinematic romps were known as, “the only sure thing in Hollywood.”

One of the buxom objects of The King’s desire in Tickle Me, actress Francine York, knows firsthand what it’s like to be wrapped in the arms of one of Tinseltown’s sexiest leading men. She described Elvis in 1965 to me as, “Not at all shy, very outgoing, great sense of humor. So gorgeous in person. Always kidding around, kiddingly talking back to Norman Taurog, the director. Very kind to me and complimentary. So different than a lot of stars who were stuck up.”

By 1968, a succession of hastily produced, impossibly anachronistic travelogues with sappy soundtracks had diminished Elvis’ star so completely he was considered washed up. With rare exceptions he hadn’t appeared in concert in over a decade, with seemingly no apparent demand for such a thing. Singles barely cracked the Top 40 (when they did) and album sales were in steady decline. American tweens had outgrown Hound Dogs and Teddy Bears, gravitating instead towards Partridges, Monkees and Cowsills.

But an electrifying performance in December of 1968 on an NBC television special caused America to fall in love all over again, arguably the greatest comeback in show business history. Within a year Elvis was riding high again on the pop charts, the biggest act ever to hit Las Vegas. Elvis’ first concert outside of Vegas since 1961 made headlines when 207,494 people crowded the aisles for six shows in Houston. Elvis took his act on the road beginning in 1970, breaking attendance records everywhere he went, but his schedule brought him no closer to Greensboro than Cleveland until 1972.

Elvis’ second rendezvous with Greensboro came on April 14, 1972.

Before the King arrived, Elvis’ advance men covered with aluminum foil every window on the top floor of the posh new high-rise Radisson Hilton on West Market (across the street from Greensboro College) to create an environment unencumbered by the outside world.

A typical day on tour began around 3 in the afternoon because Elvis partied with his bandmates past dawn. Other than getting in and out of a limousine, the group wouldn’t see the light of day for weeks on end. As one of The King’s attendants put it, “At a point you get nuts.”

Documentary filmmakers who had been recording the stage show since April 9th rejoined the tour in Greensboro after a short hiatus. Concerned that the project might be scrapped, a screening of the assembled footage was arranged at a local theater for Elvis’ manager Tom Parker. The Colonel was enthusiastic about what he saw and eager to continue.

For this show Elvis wore his Royal Blue Fireworks outfit, open to the waist, with an Owl Belt and matching cape, draped with one of his trademark scarves, which would be occasionally bestowed upon an adoring fan. His every twitch sent forward ripples of excitement, fever-pitched screams, Instamatic cubes flashing like strobe lights, hands reaching out as if to touch what surely seemed to be an apparition but, no, was The King of Hollywood and Las Vegas, every girl’s teen idol, here before them.

Estelle Brown of the Sweet Inspirations told BBC2, “When Elvis walks out on stage it’s like the building is being torn down. People were screaming and hollering and falling out and throwing stuff on the stage, oh, it was just amazing. Not only did he have the Sweets and the TCB band, but he had the gospel quartets like The Stamps or Imperials. If you include the orchestra it would be about 60, it was a lot of people on stage.”

Cameras rolling, Elvis had in mind to attempt a new song this night, one he’d recorded a few weeks before. Apologetic about holding the lyrics in front of him, Elvis rendered a rousing performance of “Burning Love,” creating yet another anthem, his last Top Ten smash. After finishing “I Can’t Help Falling In Love” with amazing vocal flourish, Presley spread his caped wings, exiting like a condor. Amid much fanfare from the orchestra, a booming voice was heard over the Coliseum speakers that spoke with a terse finality: “Elvis has left the building.”

After a two-year absence, the Coliseum sold all 16,000 tickets for Elvis’ return to Greensboro on March 13, 1974. Within minutes scalpers were able to command $200 for a front row seat that cost them $10.

The King was looking sharp in his high-collared, Blue Starburst belted jumpsuit with wildly exaggerated, pleated flairs. Pointing out a child in the audience outfitted in a sequined jumpsuit and cape, he brought the boy on stage, draped a scarf around him, then commanded jokingly, “Get him out of here, he’s dressed better than I am.”

There was considerable drama surrounding Elvis’ 1975 engagement here. He and his entourage deplaned shortly after midnight on Monday, July 22nd, from his newly acquired, 96-seat Convair 800, christened the Lisa Marie. The airplane was customized, like all his vehicles, by 1966 Batmobile designer George Barris, who equipped it with an executive bedroom, teak paneling, gold bathroom fixtures, a fifty-two speaker sound system and a sophisticated videotape network.

Moments after settling in at the Hilton, word went out to the Greensboro Coliseum that there was a problem. Armed with a telephone and a copy of the City Directory, the Coliseum’s harried manager began waking up local dentists starting with the A’s until he found someone who could see the star of that night’s sold-out concert for an emergency procedure. It wasn’t until Dr. J. Baxter Caldwell’s patient sauntered in around 3:30 a.m. that the Greensboro dentist realized he’d be working on the most famous mouth in America, drilling behind the upturned upper lip of the King of Rock ’n’ Roll. Returning to the Hilton after the procedure around sunup, Elvis dined on a fruit tray before heading off to bed.

Ironically, Dr. Caldwell was known for his reluctance to use painkillers on his patients. Two days later in Asheville, when the dentist there left the examination room, Elvis had reportedly ransacked the premises looking for drugs. It had become a common practice for Presley to remove a filling in one of his teeth so as to be seen on a rush basis for what would eventually yield him a prescription or two. It was also in Asheville that Elvis — angry that his personal physician, Dr. George C. Nichopoulos, had taken away the drugs he’d scored from the dentist that day and perturbed by a rolling vertical hold — had fired a bullet into the television set at the Rodeway Inn. Biographers say that the bullet ricocheted into Dr. Nick’s chest but caused no injury.

But back to Greensboro. Christopher Newsom shares a snapshot of Elvis leaving the Hilton for the Coliseum on July 22nd, “My dad and his brother went and waited for him to come out. His bodyguards told everybody he had a toothache or something and wouldn’t be hanging around to talk.”

Elvis had been inexplicably pestering his female backup singers from the stage for several nights with crude insults, serving up most of his vitriol for on-again, off-again girlfriend Kathy Westmoreland, who harmonized with the Sweet Inspirations. When it got to be too much, all but one of the women walked off stage mid-performance in Norfolk on July 21st. They had decided to quit then and there, but finally agreed to make the trip to the Gate City without saying whether they’d go on or not. After a heartfelt apology from Elvis, all but Kathy performed at the Coliseum on the 22nd.

One reviewer declared the show that night, “better than ever.” After returning to the dentist’s office for a follow-up, Kathy met with Elvis as he sat on his bed in karate pajamas brandishing a gun in one hand and a gift-wrapped watch in the other. “Which do you want, this or this?” he asked. She nervously took the gift, agreeing to stay on until the end of the tour.

More bewildering, the next afternoon all of those who were supposed to be flying on to Asheville for the final three nights of the tour discovered, upon arriving at the airport, that Elvis had left the tarmac and gone ahead without them. After the plane was sent back and they finally arrived at the Rodeway Inn, Elvis was in a contrite mood. Summoning the jeweler that traveled with a portable jewelry store in case he was feeling generous, Elvis purchased everything he had on him, with more flown in from Memphis, to be distributed to everyone in the roadshow. He took the $40,000 diamond ring off his finger to give to J.D. Sumner of The Stamps. When The King didn’t receive his customary standing ovations in Asheville, he doled out expensive trinkets to audience members, expending some $85,000 all together, then handed over his guitar to a random fan (who, just this year, tried unsuccessfully to sell it for $300,000).

Like a man possessed, two days later he presented the Colonel with a Gulfstream jet and, on Sunday, July 27th, gave thirteen 1975 model Cadillacs totaling $140,000 to band members and another to a lady admiring his personal Caddy parked in front of the dealership. When she told him her birthday was coming up, Elvis had a check written so she could buy some new outfits, “to go with the car.”

By his next Greensboro appearance on June 30, 1976, a theatrical practicality had taken over. Presley only pretended to play guitar, his moves now mere poses. The audience lapped it up nonetheless. Elton John met Elvis backstage a few nights before this show in Greensboro and stated, “He had dozens of people around him, supposedly looking after him, but he already looked like a corpse.”

Every year in the Gate City Elvis wore a different outfit, in 1976 the Blue Egyptian Bird. When he wore this elaborately beaded getup for the first time in March he ripped the seat of his pants and made front pages headlines all around the world. Elvis in 1976 was described by close associate Red West as, “A boy in a man’s body who could not handle the celebrity he had now become. I had a sinking feeling that I would not see my best friend again. And I didn’t.”

By spring of 1977 when he performed in Greensboro for the last time on April 21st, the King of Rock ’n’ Roll was on a years’ long rockin’ roller coaster of amphetamines and downers. A full-time nursing staff and a retinue of unknowing physicians in every time zone reportedly kept Elvis Presley medicated between near-fatal overdoses and brief bouts of drying out.

Weighing in at over 250 pounds, with a little over a million dollars in his checking account and $500,000 a month in expenses, the King was effectively broke after a lifetime of hit records, movies and sold out concerts. Regardless of his precarious health and chemical dependencies, Presley needed to be constantly on the road to make ends meet. Opening venue for what would be the last ten weeks of concerts before his untimely death was Greensboro, about which Elvis declared from the stage in more coherent days: “Of all the places we’ve been to, you’re one of the most fantastic audiences we’ve had.”

The enthusiastic capacity crowd of 16,500 at the Coliseum was treated to one of the strongest and most exuberant of what would be The King’s farewell performances. Wearing his golden Mexican Sundial suit, Elvis was feeling so frisky he sang three songs he’d long ago dropped from his repertoire: “Little Sister,” “Little Darlin’” and “Fever.”

He could still send shrieking shock waves throughout the audience with a mere turn of his head but pelvic thrusts were a thing of the past. Action on the stage was reduced to dispensing as many scarves as possible, his naturally drowsy eyes now woozy winks.

Small wonder. Elvis had been prescribed more than 5,300 pills while on the road, a mind-numbing cocktail of opioids, amphetamines and central nervous system depressants that included (get out your Physician’s Desk Reference): valmid, placidyl, valium, pentobarbital, phenobarbital, butabarbital, dilaudid, demerol, morphine, biphetamine, amytal, percodan, carbrital, dexedrine, cocaine hydrochloride but most especially codeine and quaaludes.

In anticipation of an upcoming tour, which would have bypassed Greensboro in favor of Asheville and Fayetteville, 600 pills were dispensed for Presley on the day before departure. It wasn’t enough. Indicative of his compulsively crepuscular lifestyle, the last photo taken of Elvis was snapped by a waiting fan as The King returned to Graceland in the pre-dawn hours from a trip to the dentist. Hours later he was found dead of an overdose. It had been a little over twenty-one years after his first show here and just four months after his last.

Elvis’ co-star Francine York appeared in dozens of motion pictures and memorable television shows like Lost in Space, Bewitched and Hot in Cleveland, starring with many a matinee idol. She even played a villainess on Batman. But The King made a lasting impression: “I will be going back to Graceland again this year with all expenses paid. It was sad being in his home for the first time in 2008 and seeing his white outfit on display with the cummerbund and watch him singing on the TV up to the left. I just loved him and find it difficult to watch his movies now, it just breaks my heart.” OH

Billy Ingram is a frequent contributor to O.Henry.