Christmas in Hell’s Half Acre

Christmas was not my family’s long suit. But it wasn’t for lack of trying. There was the requisite twinkly tree (fresh only, never “arty” as my mother would say.) There were hand-made evergreen wreaths and swags, fashioned by my grandmother’s clever hands. There was a modest amount of packages under that fresh tree.

More about the packages later.

There was even, God help us, homemade fruitcake (two varieties, one called an icebox fruitcake, and then the bourbon-soaked variety that over the years became more a bourbon fruit mash, thanks to liberal drizzling of spirits). Slosh enough liquor over fruitcake, and you will find takers, I promise you. Namely, my father’s devoted employee, Howard.

It is hard to identify exactly what went so wrong with Christmas. Perhaps it was because we were not living on Walton’s Mountain, home of homilies and happy endings. We lived in Hell’s Half Acre, which is instructive. And the hard fact was, most years Christmas was a bust.

Did we try too hard? I don’t think so. We were a tribe of misfits, who knew what the holidays were supposed to be like thanks to the Waltons, but couldn’t find the damned manual.

Even a kid could see we got it wrong. There was the year that my father gave my mother a mailbox, which he bought at the hardware store on Christmas Eve. He never wanted to go Christmas shopping until late on the 24th, when the hardware was the only establishment open. Even my child self knew enough to warn him it was a bad idea; Dad said he would write Mom a nice letter and put it inside.

One of us wrapped the thing, but this bad idea wasn’t something that stiff cheap wrapping could improve. There was the clear outline of the mailbox flag, undisguised by dancing reindeer and made more lurid by the liberal use of Scotch tape. When my mother saw us maneuver it under the tree she was so pissed off she slung a red high heel across the room as she heard the front door open, thinking my father was home. The heel struck Howard squarely in the head just as he entered the foyer.

Howard, a painful introvert, required a shot of courage just to make a friendly visit. He was a fixture at our house come the weekend, and although our mother tolerated him, he clearly got on her nerves. My father, a teetotaler, hid Howard’s Wild Turkey in the dishwasher, which hadn’t worked for years, and served as a bar. (Dad seemed to think we wouldn’t know where the liquor was if he put it somewhere related to kitchen chores.) Howard was one of those drunks who had a compulsion to tell the truth. Once under the influence, Howard alone had the guts to tell our mother what he thought of her cooking after a trip to the dishwasher for a swig.

Ho-ho-ho.

While my mother didn’t carp, “Why didn’t you duck?” after clocking Howard, I don’t recall her exactly cringing at what she had done.

Howard the Melancholic took it well. Fortified with the right amount of spirits, he touched his forehead, took a look around and asked us kids if we wanted to go to the drive-in for a cheeseburger.

Oh, yes. We did. (Forget how drunk Howard was; we eagerly climbed into his Oldsmobile.)

It seemed that Christmas brought out Howard’s deepest angst. He aired his personal regrets concerning his wife, Ruby, the woman Howard felt he had deeply wronged by marrying. His was existential, grinding guilt. She was, he said again and again, too good for him. And he was not being ironic.

“Now, Ruby is a God-fearing, good woman,” he would slur, as we chewed French fries, slurped milkshakes and nodded without comment. The little dive had the best burgers anywhere. And there was no point in interrupting, which even our baby brother grasped in time. Howard was stuck on one channel — the Guilt Channel — and it played 24/7 in his heavy head.

“Ruby doesn’t drink,” he intoned. Won’t touch a drop. A Christian woman.” What we saw was a shriveled, humorless woman, who never smiled. But he praised how she kept a clean house and a plate in the oven for whenever Howard found his way home.

“She knows the Bible, too. You ought to hear that woman quote the Bible.”

We listened, even though we squirmed, but stayed with his wandering monologue until he tootled with us back home. Although Howard dusted a few ditches, he largely kept in his own lane.

We would have taken a bullet for Howard. It wasn’t just the burgers. He screwed up.

And that is where our lives intersected with his. It was the remorseful screw up, Howard, whom we identified with, not the Scripture-quoting Ruby. Childless, he was unfailingly kind, buying magazines when we hawked them for the school, as well as boxes of World’s Finest (and most overpriced) candy bars. Sure, Howard was a mess, but he was our loving mess, and much more complex than Otis on The Andy Griffith Show.

Otis was a TV character. Howard was real: a kindly, hard-working failure. His Ruby reminded him of that fact throughout their married lives.

Howard was also our guide to the perils of adulthood, which actually looked a lot like the perils of childhood from the backseat of the Olds.

By the age of 10 my siblings and I understood that bad marriages happened to good people. Our own parents took 35 long years to finally divorce.

After marrying at the reckless age of 17, my parents’ divorce was like climate change: Nobody wanted it to happen, but if you had eyeballs you surely saw it coming.

But Howard and Ruby, bound inexorably by good old Christian guilt, never split.

In stark contrast to the miserably silent H&R were Deanna and Olin from next door, whose fights were so legion their young son Beau would knock on our door and ask to spend the night. Deanna was no long suffering Ruby. She was a leggy blonde who walked around barefoot in Daisy Dukes. Olin, also easy on the eyes, was golden tan and built to wear jeans.

Equally beautiful and jealous, both accused the other of the worst. They were volatile. Deanna threw a steak knife at Olin and hit him. Without a word, she packed Beau and the baby, Josh, into her convertible and split for Vero Beach, Florida.

I cried bitterly, not only because we could no longer snitch cigarettes from Deanna and watch any TV we liked while babysitting the kiddos, but she was my friend. And Deanna was a member of the Book of the Month Club(!) She shared summer reading that was much more interesting than what the Bookmobile offered.

Vero Beach sounded pretty damn good to me. I looked it up on the map; my father’s trucking company routinely hauled loads of Indian River citrus fruit. Vero Beach was just too far to consider spending Christmas there.

Once, Howard had taken a flight to Los Angeles, then got right back on a return flight without leaving LAX. (He had always wanted to see the West Coast, Howard explained between hiccups.)

But I vowed something to myself. If I lived to be 16, which sometimes looked dicey given my riding with a drunk driver for a cheeseburger, I would haul ass, too, and find my friend Deanna and the kids.

Later I watched as Olin sat on the back steps and cried, his broad shoulders shaking. It was too much to take, and I went to my room, fell onto the bed, and did the same.

That year was an especially bad Christmas. No purloined ciggies, books nor trash TV. No fun, really.

So, we kids turned to our drug of choice: Stuff.

I yearned for something useful, like a tape recorder. A book. A cowgirl outfit like my sister’s. Anything but a doll, please, Baby Jesus! When I tore away the wrappings, what I found was a blonde Revlon doll in a black cocktail dress and stilettos. I am unsure what I did with that bimbo, but I do recall devoting much of my childhood to wrenching a doll’s head from the torso faster than the boys could solve a Rubik’s cube.

Which is why I pried away my younger sister’s Chatty Cathy explaining that I could turn it into two useful things: a tape recorder and a doll. I set to work on Chatty with my father’s screwdriver, and after destroying the doll discovered the box played inane phrases but could not record. Kim, robbed of her new doll, turned blue from holding her breath after first screaming bloody murder, and has not, not even today, forgiven me.

Was it my worst Christmas?

It was up there in the annals of worsts.

Chatty Cathy was expensive, and I knew there would be hell to pay for my destroying her. Anticipating corporal punishment, I found the buggy whip my father kept in the garage with an ancient carriage and hoisted it far into the attic. My Dad hated heights. If, in a fit of anger, he thought a buggy whip would be just the thing to teach me a lesson, I would remove all temptation.

If things had been different I might have gone to Deanna and Olin’s house. But it was dark, and nobody was there, which I knew because I checked often, hoping.

I sat in the garage, hugging my knees, shivering with the knowledge that not everything works out just because it’s Christmas. Not expecting much, but still, hoping to hear Howard’s Olds crunch across the gravel. — Cynthia Adams

Gone to the Dogs

When your worst Christmas ever is also your best, calling it bittersweet would wrap it up with a tidy little bow. But as we all know, life isn’t that cut and dried — in fact, it’s rather messy most of the time (like my gift-wrapping skills). The year was 1989, and, at 9 years old, all I could think about was having a puppy to call my own. But not just any puppy — one that I circled at the top of my dog-themed stationery — the absolute living end of cuteness: small, golden, with floppy ears.

I woke up Christmas morning bright and early and heard something I thought might be a radio. It turned out to be the yipping of my heart’s desire: a cocker spaniel puppy. My siblings and I could hardly believe it. Santa had come through. We were also given Hungry Hungry Hippos that year. When Sandy the puppy wanted to play, he pushed one of the levers with his paw, and a single white marble rolled into the middle of the gameboard. The three of us kids melted instantly.

Once school started up again, it was back to reality. I impulsively told the friends who sat near me that Santa had given me a puppy. I received some blank stares. Nobody said anything. And in my heart of hearts, I knew they didn’t need to. “Santa doesn’t really exist . . . does he?” I stammered. Wow. Guess I was a little slow on the uptake, but I got over it quickly.

As the days went by, Sandy showed a less-than-adorable side, including lots of ankle biting, carpet staining and who knows what else. I was so in love I tried not to notice. One day after school, my mom told me she gave Sandy away to an “old lady” and that it was all for the best.

I was in a state of disbelief. My sister and I went to the basement to see if our puppy was there. No dice. When my brother heard the news, he took off on his bike. As children, it was hard to understand why it happened that way. Like puppies, life has its ups and downs, but as the title of one of my childhood books advises, It Could Be Worse!

But why would you do that? Why didn’t we get to say goodbye?

And why on God’s green earth would you unleash Sandy on a nice old lady?! Not to mention, our rounds of Hungry Hungry Hippos were never the same. — Annie Ferguson

A Dickens of a Christmas

A few days before Christmas of 2001, I jettisoned my Web design business, fired my clients, chucked everything into storage and relocated to London. Thanks to a not-so-honest cabbie (“Do all the parks in this city look alike or are we driving in circles?”) I made it to my flat with exactly £10 to my name.

My Website, TVparty.com, was churning out tens of millions of page views every month, one of the Internet’s first multimedia sensations, but there was no way to monetize that traffic. So I engineered a system whereby users could pay $5 for premium content (radical idea, huh?) resulting in deposits of between $0–60 a day to my debit card. Not much dough for living it up in one of the most expensive cities in the world but my future was so purposely uncertain I couldn’t have been happier.

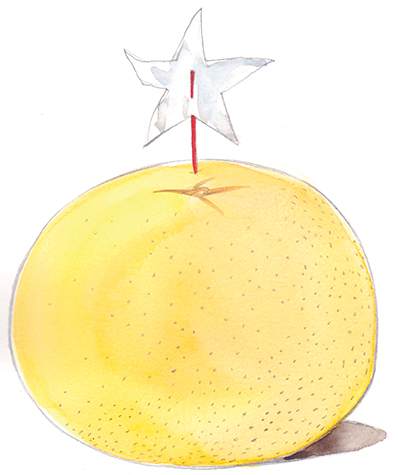

Not knowing anyone in the city (my roommate was out of the country), I banged away at the keyboard with happy abandon in a top-floor flat overlooking Brixton, Europe’s melting pot (and home to a notorious prison.) When the morning of the 24th arrived, I gathered all the cash I had, a single £1 coin, and walked to the green grocer up on the high street where I came across a Florida grapefruit selling for exactly that amount. Returning home, I placed that juicy orb on the mantel above our nonexistent fireplace. It became both my Christmas present and tree. The next morning I savored that grapefruit (sprinkled with salt not sugar) while watching reruns of Bewitched and Sgt. Bilko that aired weekday mornings on the BBC.

Around 10 that night, a Christmas miracle occurred—I banked a staggering £3! So I jauntily headed out for a nightcap at one of the many pubs that lined the high street. The thoroughfare was eerily quiet, no cars moving about, with only one pedestrian in sight, a lady of the evening (it was cold that night so let’s call her Prosty) who asked if I, wanted a go. Which I rightfully reasoned was Londonese for, “You new in town, sailor?”

Respectfully declining her offer, the only holiday invitation I received that year mind you, I arrived at my destination only to discover all of the pubs were closed. I now had to walk back past Prosty again; naturally she propositioned me once more because, of course, I’m behaving just like a ‘John’ would. I again politely begged off. As I’m nearing my flat, I hear a commotion behind me. Prosty’s pimp had emerged from the shadows to physically berate her in the middle of the empty street. I yelled back to him, “Hey, it’s not her fault! I only have £3, and it’s on a card!”

The story’s not entirely bleak. In a nice Dickensian/O.Henry twist, it turns out living in London that year helped me land my first book deal, which led to writing and performing on five hours of Christmas Specials for the Bravo network from 2004–05. — Billy Ingram

Heave Ho! Ho! Ho!

It was so festive, the sanctuary of the Episcopal church my family and I attended, adorned with greenery, poinsettias and flickering candles. I was 16 at the time and, clad in a sleek knit dress and my first pair of high heels, I felt oh-so-grown up, as I sat wedged between my two college-age sisters. Except for the butterflies in my stomach that came with a the opening notes of a trumpet blasting out “O, Come All Ye Faithful,” while the “faithful,” convivial late-night revelers donned in gay apparel packed the church’s pews after making the rounds of holiday cocktail parties.

The service, which is to say, 30 minutes of calisthenics — standing, sitting, kneeling, sitting and standing again — got underway, and midway through, the lights dimmed while the congregants lit small tapers and knelt while singing “Silent Night.” Long about the last stanza about “radiant beams,” I was enveloped by the miasma of Johnnie Walker emanating from the gent enthusiastically swaying on the prayer bench behind me, fearful that he might send the congregation up in a conflagration as he warbled out, “Jesus Lord, at thy bi-irth,” with gusto ill befitting the carol. I began to feel a little over-radiant myself, the sweater dress becoming uncomfortably warm, as the butterflies fluttered anew.

The lights came up and it was time to stand again. And as I began to rise, so did a tide in my stomach, causing me to wobble in my high-heeled shoes, while tiny beads of sweat formed on my brow. The butterflies were in full migration. How could this happen? Then I remembered: “I’ll fix you an omelet,” my bossy eldest sister had announced earlier in the day. “You’ll love it,” she had assured me.

Famous last words from the family Shakespeare scholar who could expound on the differences between the First and Second Folios but historically had trouble finding her way around the kitchen.

Tonight it was Omelet’s revenge. To heave or not to heave? That was the question. The answer came upon this midnight clear beyond the blurry pages of my prayer book and filled me with panic. For there, on the seat of the pew in front of me lay a swath of shiny, thick, dark fur with a satin lining splashed with a single word, “Blackglama.” Its owner, a carefully coiffed duena had cast the mink aside during the heat of “Silent Night.” Little did Glama Girl know that her luxurious wrap, perhaps a wedding anniversary gift that had no doubt seen countless Christmas Eve services, cocktail parties and opera galas, was about to witness a baptism — its own — in of a morass of semi-digested Large Grade A eggs, cheese and onion.

Luckily, came a true Christmas miracle

I sank back down into the seat of my pew, hand clamped over my mouth, fearing what an “Ahh-men,” might produce, while my mother shot daggers at me for my presumed act of sacrilege. And then came the peal of the trumpet again, signaling the recessional, “Hark the Herald Angels Sing.” Or in my case, a barely avoidable “Hock.”

But for the grace of God went I without incident, down the aisle and into the cold December night, bypassing the rector’s outstretched hand.

Later, in the wee, small hours of Christmas Day, the holy spirit moved my troubled insides, and the tide that I had successfully held back in church, came forth, leaving me weak as a kitten during the ensuing merriment and gift-giving. While everyone else in the family devoured my mother’s delicious cranberry bread, I nursed a flat ginger-ale and tentatively bit into a Saltine cracker. Then came the shriek of “Eewww, gross!” It was my middle sister, the true culinary whiz among us three, who had reached into the refrigerator and produced the carton of eggs.

“Has anybody checked the expiration date on these?” she asked.

Looking up from the book she’d been engrossed in, our eldest sister paused as the implication of the question registered. “Oh,” she said. “I guess I forgot.” — Nancy Oakley

Trailer for the Horror Film: The Attic

{Fade in tight on a coal-burning fireplace.

{Camera pulls back slowly to reveal the living room of young Harry’s grandparents’ home. It is 1953 and the scene is in full Christmas Eve mode. Eight-year-old Harry sits in a chair next to the decorated cedar tree. His parents and grandparents are generally ignoring him, their attention is focused on Harry’s new baby sister. This is an after-supper rest period, the hour or so for socializing before bed. Harry is eyeing the wrapped presents under the tree and getting sleepy. His mother notices.}

MOTHER: Ready for bed, Honey?

HARRY: Mmm. Yeah. Guess so.

MOTHER: Well, your father and I and Mary Jane are sleeping in the back bedroom this year. And you’re going to be sleeping in the attic. Won’t that be fun?

{Close up of Harry’s supershocked face.}

{Cut to Harry’s father in the hall, pulling down the folding ladder to access the dark attic.

{Point of view: Harry. His father gesturing for him to go on up. He climbs the ladder to the blackness. He turns to see his mother climb halfway up.

MOTHER: What an adventure! You’re so lucky! Please don’t mess with those toys in the corner. They belonged to Douglas, our little brother who died when he was 4.

{pause}

Nighty-Night!

{We see her climb down and close up the folding stairway, plunging the attic into total darkness.}

{Cut to close-up: Harry’s wide-open eyes in a sea of black.} OH — Harry Blair