Art and Nature

Michael and Joan Mattingly’s colorful, Frank Lloyd Wright — inspired house and garden

By Cynthia Adams • Photographs by Amy Freeman

Two bright young Midwesterners met in The Chicago Bar in Omaha, Nebraska. He was from Missouri, she was a native Cornhusker. Michael Mattingly was in medical school at Creighton University; Joan was studying to become a nutritionist at the University of Nebraska Medical Clinic rather than pursuing art as she secretly desired.

They clinked glasses and clicked. The handsome couple married twice; once secretly, and again three years later, making for a cheering, affirming story about love conquering all. These 31 years later, the Mattinglys are toasting a long and happy union.

“I didn’t want my dad to get upset and not pay for medical school,” Michael explains. “We met when we were 21 and married when we were 23. We are defying all odds.”

Even his six siblings didn’t know. “We went on a cruise three years later as our honeymoon, then came back and had a reception,” Michael remembers.

“It doesn’t usually turn out that way,” Joan muses.

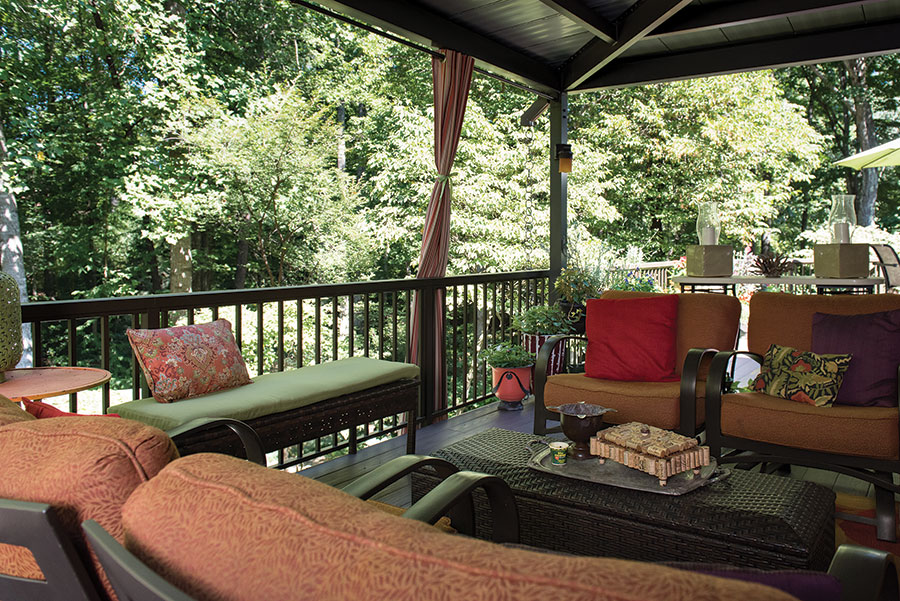

On a Friday afternoon, Riedel glasses in hand, they are at home, watching the sunset from their back deck overlooking a placid scene of their verdant backyard and sipping a nice red, a Napa blend.

Red is Joan Mattlingly’s favorite color, by the way.

In their northwestern Greensboro house, the Mattinglys have created a “soft contemporary home,” meaning, an infusion of Asian and organic influences — a nod to a much-admired fellow Midwesterner, Frank Lloyd Wright. Something about the spacious lots of their neighborhood reminded them of the Midwest and they committed to their new surroundings, fully infusing their energies into house and landscaping.

And it nearly didn’t happen.

After a long search for a Triad house with contemporary lines, the Mattinglys found an approximation of their dream home back in Rock Hill, S.C. “We started looking here in 1996, and moved in 1997,” says Michael, now a specialist in nephrology at Carolina Kidney Associates. “Our other home was ultracontemporary.” Joan noticed their current house while being shown another on the same street. Fortunately, it became available in less than a month. They acted quickly.

Good friends back in Rock Hill immediately scooped up their home and the Mattinglys moved to Greensboro. “I loved the neighborhood,” says Joan.

The house had aspects they liked that read faintly Asian and thereby Wright-like: the low-slung rooflines, generous decking and the orientation to the deep backyard.

The pair set to work, transforming the stark interiors — white tile or carpeted floors, white walls, white Formica and all surfaces were all dramatic white with only a touch of navy — into an earth-toned home more organic and to their liking.

“It was a showplace,” says Joan. “Decorated to the nines.”

They exchange a look. “But we had a 1 1/2-year-old.” Their daughter, Emma, is now grown and living on the coast in Wilmington.

“We’re not into cold contemporary,” Joan explains. “People immediately think of contemporary as austere. It was beautiful,” she concedes, “but not for us.” Even the exterior flowers the owner had planted were all white. The owner told them “this house doesn’t lend itself to color.”

“Well, that won’t last long,” replied Michael.

Joan shrugs and smiles. “Color works here.” They’ve since painted every room, some twice, in various earth tones. “We do it all ourselves,” says Joan. Out went marble and clinical tile. In came cork and wood, many of the woods exotic and imported. Some rooms were given a coating of a burgundy color.

Most recently, they installed dramatic double front doors made in Honduras. “I waited 21 years for those,” says Joan. They added side panels of rain glass to bring in dramatic beams of light to the foyer. They both laugh about the adventure of getting those specific doors — perhaps a story for another day, they say. Their house that is rife with stories about evolving, given that the owners patiently waited for just the right thing.

The kitchen, which bears discussing, is also built with color and texture in mind. And wood. Here, they elevated the kitchen ceiling, lifting it up and widening doorways, while enclosing an adjacent rear porch. “We wanted it more open,” Joan says.

“We had also fallen in love with wood. We fell in love with cork.”

The north-facing kitchen, situated over the garage, had a cold tile floor. They installed cork flooring in a bathroom and then in the kitchen in 2003, opting for sustainable, forgiving materials.

At the time, cork as an interior surface was extremely rare, the Mattinglys stress. “No one had cork,” Michael offers. “It’s kinder,” Joan adds.

Woods take center stage in a kitchen that features several exotic varieties. The contemporary cabinets are maple, cherry and zebra wood, designed and built by local woodworker Grant Newton. Overhead are colorful Millefiori glass light fixtures. Joan rests an elbow on the red quartz counter. “We load up that bar and we flow; this is where everybody comes during a party.”

And art is abundant here and elsewhere. “Mike made that,” Joan says. “He created a sculpture from corks. I contributed by drinking wine,” she laughs.

There are witty metal sculptures there by local artist Frank Russell, titled Obstinate Lobster, fashioned, in part, with the leg of a wrought iron garden bench; Yo Yo Ma (a fish sculpture with eyes made out of yo-yos), and Redneck Fish, so named because its body is made from a guitar. Most of their art is local. Joan has close friends who are artists, including sisters Carey Jackson-Adams and Nancy Bulluck.

She collects her favorite red pottery from Seagrove potter Ben Owen.

The couple attend Winston-Salem’s Piedmont Craftsmen’s Fair every year after Thanksgiving and usually return with another art piece. The list of collected artists is long. Bailey Wharton created a lot of their wood pieces. They have also collected paintings by Kim Kesterson Trone. But they are especially fond of a Brian Hibbard painting —an exception to local artists in the collection.

“Everything has a story,” says Joan. “We have been so lucky to fall into such a beautiful art world here.”

They installed Shoji screens in their master bedroom and bath. “We just liked them. It’s ageless contemporary. Grant made them from unique woods and created the cabinetry.”

It is methodically conceived and executed. Shoji screens also conceal sliding doors to the back deck.

A formerly “sterile” powder room was painted in the style of Austrian painter Gustav Klimt by Joan and an artist friend from Rock Hill. It remains as painted, 22 years later. Joan says she still loves it.

A sculpture on their hearth, acquired when they lived in Scottsdale, Arizona, is made from the skeleton of a sorrel cactus. It is surprising and organic — something that repeats through the house and garden — another revealing imprimatur of Frank Lloyd Wright, whom Michael says is the artist he would most love to have met.

The woodsy exterior space is where Michael Mattingly’s effort shines. He had ample space within which to work, with nearly an acre lot.

He culled pines and sweet gums, making way for a vision. The vision is fully realized. Now, the landscape is utterly private and green, like a Julius von Klever painting. It is lush and dappled by afternoon light. Here too, Joan says, is where Michael finds solace from work.

“This is where I live,” both say at different moments, standing on a deck made intimate with the addition of a covered porch, which serves as an outdoor living room. It was built last year after the couple admired something similar in Scottsdale. “The restaurants all had covered terraces, and Michael felt we could recreate it at home. Jay Snyder, a local metalworker and artist, created their fencing and artful rear gate; he also designed their rain chains, says Joan. “He had never done a structure like this.”

Early on, Michael consumed landscaping books, and after a year of mulling things over, he began shaping the backyard with careful intention. “I had dump trucks, four loads, to come in. I had to rent a Bobcat and move all this dirt, then put up a retaining wall.”

Despite the hard labor, the physician finds release in his many projects. “He comes home and I watch his shoulders relax,” says Joan.

While the front yard is straightforward and well-groomed, the back of the property is magical.

“I compare our house to a mullet,” he jokes. “Serious in the front and a party in the back.”

Vines were choking azaleas and other plantings until Michael reshaped the mess into a controlled vision that now seems utterly natural.

“I call it planned chaos,” he says.

And that river rock lining dry creek beds and French drains that look like the cunning handiwork of Mother Nature? It was put in place by Michael — all 18 tons of it, brought in on 12 pallets.

Ditto for clearing many cords of wood, pines and sweet gums with the injuries to prove it, Joan says. Then he made natural pathways mulched with cedar that crisscross the property. There are small bridges, a pergola, arbors and many birdhouses. The manual work forged a closer relationship to nature.

A consultation with Triad landscape designer Marguerite Suggs (a birthday gift to Michael from Joan) led Michael to shade-loving plantings.

Joan says, “We transplanted indigenous fern, planting them in this gully. We call it Fern Gully.” Now fawns and foxes are commonplace in the habitat that took hundreds of hours of labor in order to look so natural and spontaneous.

Some of the fawns were born on the property, Joan observes, “Wouldn’t you want to bring your baby here? I would.”

A small pond has a witty design. “It’s a kidney shape,” Michael quips. “I’m a kidney doctor.” Owls and raccoons attacked the koi there despite all efforts to repel them, so they no longer stock it. But they do actively court birds.

“There are a lot of birdhouses . . . we love the birds. Probably half of the birdhouses, we made,” Joan notes. “When we changed the house roof, Mike created things from the copper.” She indicates copper garden features as examples. “Mike made many of the arbors.”

Repurposing materials shaped many designs for their projects. “One of Mike’s passions is cigars. At the back of the property is one of the most unique birdhouses you’ll ever see, made out of cigar tubes.”

“There are endless options,” says a smiling Michael, who is still plotting projects.

Houses are at the edge of the property; yet, it is completely quiet and only an impression of a house is visible through the foliage. The fawn, the owl, the raccoon recede into wooded quiet. A small shed at the rear of the property is nearly invisible, yet part of a unified design.

Things artfully disappear.

Even a Japanese maple is so perfect in formation it could be mistaken for a sculpture as it adjoins other outdoor art on display. Everything is permeated with a meditative calm.

When Wright discussed design, he admonished to “Study nature, love nature, stay close to nature. It will never fail you.”

The Mattinglys manifest the master’s advice. OH

Cynthia Adams is an O. Henry contributing editor. She can be reached at: inklyadams@aol.com.