For next year’s 250th anniversary of the Battle of Alamance, the Regulators get their due as early sons of liberty

Story and Photographs By David Claude Bailey

Two-hundred-and-fifty-two years ago, two of Ted Henson’s ancestors signed a petition complaining about unjust taxes, exorbitant fees and rampant corruption of Colonial officials — with no idea that they — and everybody else who made their mark or signed similar petitions — would be branded outlaws as members of the Regulator movement. Later, two petitioners were summarily executed, others were apprehended by Gov. William Tryon’s provincial government and marched all about the countryside in chains before six of their number were hanged by the neck until dead in the courthouse square in Hillsborough.

“They were not revolutionaries,” Henson, a former teacher and retired school administrator, insists. “They said again and again that they were not trying to overthrow the British government. What they wanted was to put regulations in place to make things fairer for the people,” he tells anyone who will listen to him whenever he dresses up in Colonial-era, backcountry garb at re-enactments. Henson assumes the fiery character of Rednap Howell — an itinerant schoolteacher and balladeer who became one of the leaders of a group of backcountry farmers. Their ragtag movement came to a calamitous and bloody end just across what is now the Guilford County line at Alamance Battlefield — a full decade before America’s Revolutionary War.

“I am very proud of the fact that my ancestors were willing to take a stand against what they perceived as unjust practices in the government,” Henson says, fixing his listener with his piercing hazel eyes. Heeding a call from the distant past, he has become the Regulators’ unofficial apologist, determined to set the record straight, especially as the 250th anniversary of the battle draws near with a re-enactment and educational programs planned for next year.

How does he respond to the descendants of Loyalists, who viewed Regulators as nothing short of ignorant and uneducated hayseeds — terrorists, in fact, who took the law into their own hands? “They tried for a number of years to get regulations placed on the local officials,” he says. “I think the Regulators were pushed into a corner and had no choice but to fight back.” When petition after petition and repeated court suits failed to make any substantial changes, “Their frustration boiled over into armed conflict,” he says. Unlike the Founding Fathers, who were inspired by Classical ideals of democracy to challenge Britain’s monarchy, “the Regulators were fighting for survival rather than any high principals,” Henson says.

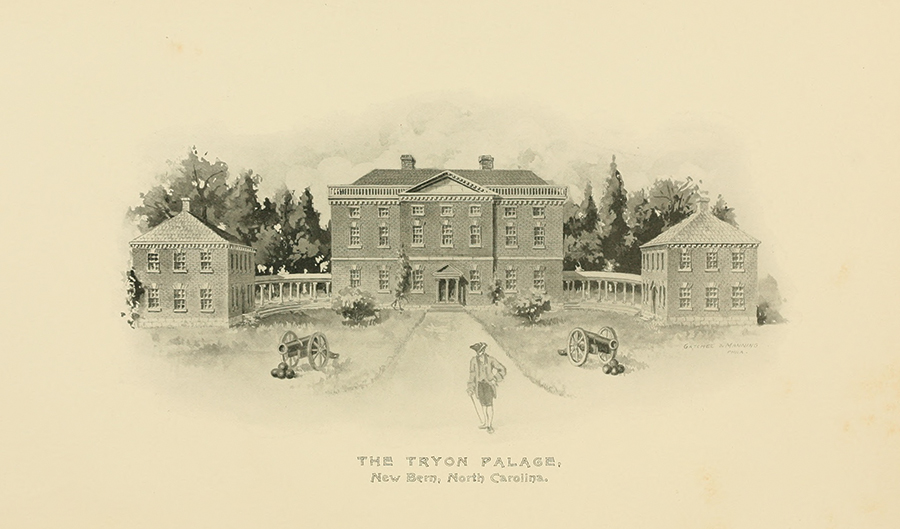

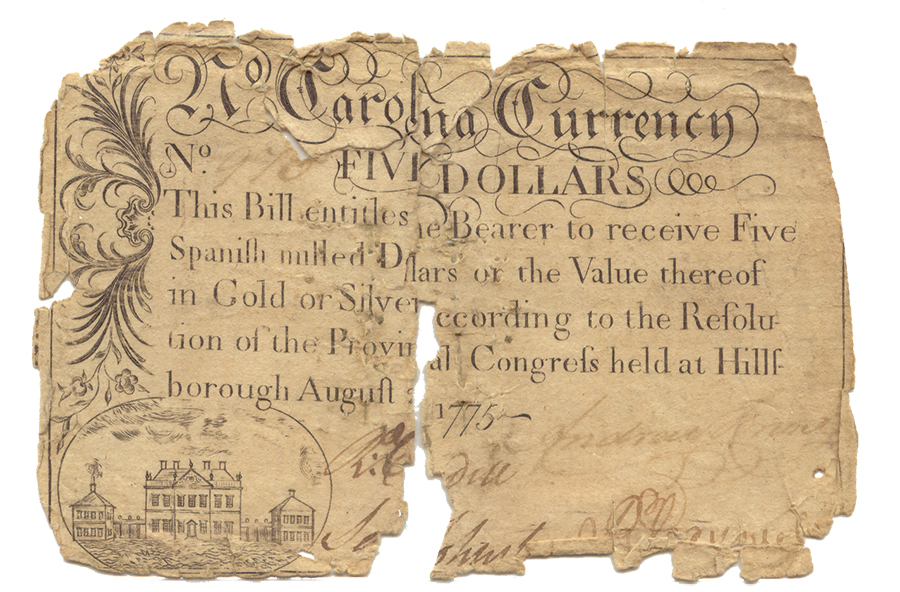

Though their grievances had been festering for some time, they reached fever pitch in August of 1766 when Regulators presented North Carolina’s Colonial assembly with their Advertisement Number One. Its complaints centered on what would become a call to arms a decade later — taxation without representation. The Colonial government was starved for funds in the aftermath of the French and Indian War. Adding to the burden was the ongoing cost of Governor Tryon’s extravagant Palace in New Bern. When completed, it was the most expensive house in all of Colonial America — a regal edifice Regulators complained they would never even see. But at the very heart of the conflict was the almost systemized corruption in the collection of taxes and fees. “There were no posted courthouse fees or tax rates, leaving a lot of room for corruption,” says Henson. Sheriffs were responsible for collecting taxes, and no less than Josiah Martin, North Carolina’s last Colonial governor, admitted that sheriffs would collect “Double, Treble, nay even Quadruple the value of the Tax.”

Perhaps equally chafing to the Regulators, many of whom were Baptists, Presbyterians and other sects that came to the Colony seeking religious freedom, was a vestry tax levied to support the Church of England. To heap insult upon injury, marriages performed outside the auspices of the Anglican Church were not recognized as official. Finally, taxes and fees had to be paid in cash rather than by barter. Scarceness of currency, especially in the backcountry, resulted in sheriffs’ regularly seizing chattel, property and land to pay taxes. This “tripped the wire of farmers’ anger and became a major Regulator target,” according to Shuttle & Plow, the definitive history of Alamance County.

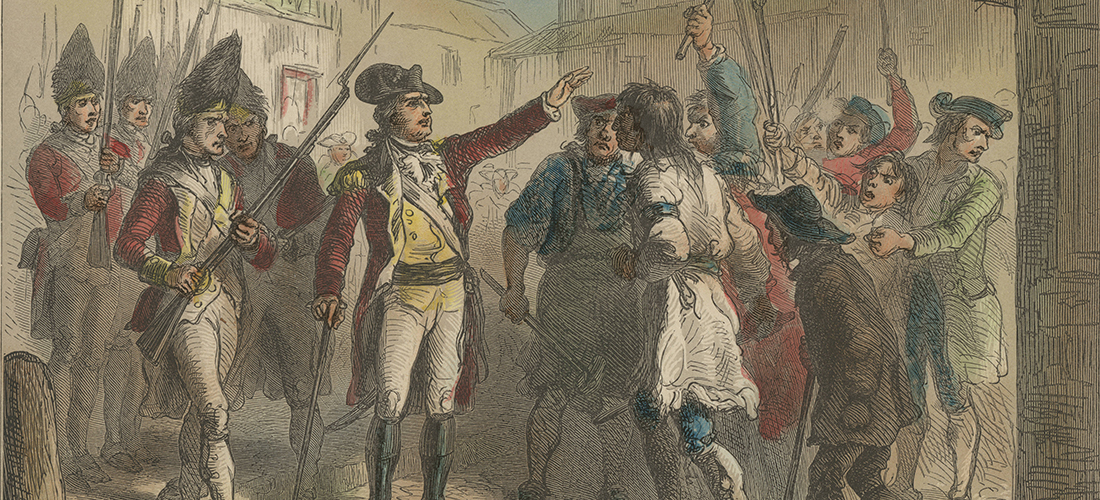

In April 1768, 70 Regulators mobbed Hillsborough to reclaim a horse that had been seized by the sheriff for nonpayment of taxes. In retaliation, the Regulators seized the sheriff, mounted him backwards on his horse and marched him through town. For good measure, they shot a few holes through the roof of the house belonging to one Edmund Fanning, the commander of the Colonial militia. A month later, when two of their number were arrested, 1,500 Regulators massed around Hillsborough. When Fanning tried to get them to disperse, he was publicly humiliated. Up to that point it might have seemed like good backcountry fun, but not to Fanning or the Crown.

In June of 1768, Regulator Advertisement Number Nine, the one Henson’s relatives signed, was presented by Howell and a co-conspirator with 474 signatures. A lot of back and forth ensued, with the Regulators refusing to pay their taxes. Mobs became frequent with 3,700 Regulators gathering for another court session in September. In response, Tryon marshaled 1,500 militiamen to protect the court. Admittedly, Tryon did officially admonish corrupt officials, but at the same time he ordered Regulators not to “molest” them.

Spiraling into increasing violence and open disregard for the law, the Regulators mobbed Hillsborough when court was held in 1770, interrupting the session and demanding that their indicted leaders be tried immediately, with a newly formed jury. Forget about the jury duly chosen by justices of the peace. They considered it stacked. According to the presiding judge who fled the scene, the Regulators “severely whipped” four of their foes, including the clerk of the court and a justice of the peace. They also entered the courtroom and hauled Fanning from the bench, dragging him out of court by the heels and unmercifully beating him before he escaped. “They tore Fanning’s house down wall by wall and scattered his papers to the wind,” Henson says.

When the assembly met for the first time in Tryon Palace in 1771, Tryon was so worried that Regulators would burn down his new home he called up the militia and had a trench dug between the Neuse and Trent rivers. The legislature enacted the “Johnston Riot Act” (later ruled unconstitutional by no less than the Privy Council) — authorizing force against any group of 10 or more people who did not disband within an hour of when the act was read aloud — which occasioned the phrase “reading the riot act.” It retroactively made almost anyone who had ever been associated with the movement an outlaw and authorized the governor to use the militia to put down the Regulator revolt. It also declared anyone who resisted or fled an outlaw. Ultimately, the Privy Council declared the act “full of danger . . . and unfit for any part of the British Empire” — but not before it had been used to justify and mount the Battle of Alamance.

When 2,000 Regulators, only half with guns, gathered in a show of force, Tryon mustered 1,000 militiamen — Colonists, not British soldiers — who massed on the banks of Alamance Creek near the present-day town of Alamance, just south of Burlington. On May 16, 1771 — 250 years ago next year — the two sides locked in battle.

Unlike much of the other history surrounding the Regulators, accounts of the battle are numerous (and often conflicting). Fans of warfare can seek them out. One highlight includes Tryon’s own militiamen reportedly refusing to fire on what, to some, were their neighbors — to which Tryon responded, “Fire on them or fire on me.” By some accounts, Tryon himself shot one of the negotiators who tried to flee the scene. He is also reported to have summarily executed one of the prisoners after the battle.

Crucial to the outcome of the battle was Tryon’s use of artillery. He brought not only cannons with him but also a detachment of sailors from Wilmington who could expertly aim and fire their six carriage-mounted swivel guns and two three-pounder cannons. Carole Watterson Troxler in her exhaustive Farming Dissenters quotes what a Moravian diarist heard from a Regulator only days after the battle: “The most important point seemed to be that the terrible cannonading of the Governor’s troops had badly frightened the Regulators, who had thrown down their arms and run, even leaving their hats and coats.”

“Gov. Tryon and his militia had a plan and executed it. The Regulators’ plan was ‘You’re all free men. Do what you think you have to,’” Henson says. When the cannon smoke cleared a scant two-and-a-half hours later, the Regulators had been routed, many of them fleeing helter-skelter, leaving their guns and other possessions behind them. By the official account, only nine Colonial militiamen died in action. Other estimates claim, at least twice that number of Regulators were killed, with something like 100 wounded. Though many Regulators fled beyond the reach of the Colonial government, those who didn’t were required to sign an oath, swearing allegiance to the Crown. About 6,000 did so. What may seem at first surprising is that only a few years later, former Regulators took up arms against the Revolutionary “Patriots” who fought the British in 1776 — honoring their oath to the Crown. (Two of Henson’s descendants fought for the Patriots, another for the British.) A month before the armies of Lord Cornwallis and General Nathanael Greene squared off at Guilford Courthouse in 1781, former Regulator John Pyle led a group of Loyalists against Greene’s Southern Army. Under the command of Col. Henry “Light Horse Harry” Lee and Gen. Andrew Pickens, the unit so thoroughly surprised Pyle’s men near the Haw River that the encounter is now known as Pyle’s Massacre. Henson’s alter ego, Rednap Howell (to whom he is not related), was of course branded an outlaw, wanted dead or alive. He fled first to Maryland and then New Jersey. Next year, two-and-a-half centuries after the battle, Henson will suit up, tune his dulcimer and channel a ballad that Rednap wrote: “When Fanning first to Orange came/ Both man and horse won’t worth five pounds/ But by his civil robberies/ as I’ve been often told/ He’s laced his coat with gold.”

Says Henson, “These men did not die in vain. Many of the demands they made would be written into the Constitution of the United States. I believe we owe them respect and gratitude for all they did for us.” OH

David Claude Bailey lives about a mile down the road from Alamance Battlefield, where he walks amidst the now peaceful woods.