Ready for Rhyme Time

And waiting . . . and waiting . . . and waiting . . .

By Nancy Oakley

Call me a philistine, but I’m a sucker for rhyme.

My penchant for verse — perverse, some would say — traces to childhood, when my mom would sing nursery rhymes, usually involving cruelty to birds, whether the infamous four-and-twenty baked in a pie or the tragic song about a robin in winter: “The North wind doth blow,/ And we shall have snow,/ And what will poor robin do then, poor thing?/ He’ll sit in a barn/And keep himself warm/And hide his head under his wing, poor thing.” This one would send me into hysterics, screaming and crying about poor robin every time she sang it. (I didn’t realize how lucky I was. A friend’s mother used to serenade her children with a grisly little ditty about the ghost of Anne Bolyen, “With her Head Tucked Under Her Arm.”)

Whether “ ‘i’ before ‘e’ except after ‘c’” or “plop, plop, fizz, fizz/ Oh, what a relief it is?” or “If it doesn’t fit/You must acquit,’” rhyme, especially when it’s set to music, grabs us by the heartstrings and stays with us. Ancient poets understood its power. Why have Beowulf and Chanson de Roland (literally translated as — hello! —The SONG of Roland) achieved epic status? Because generation upon generation could remember those heroic stories made more heroic by rhyme. Don’t believe me? You should hear my colleague David Bailey sing Homer’s Odyssey, as Homer did to his audiences 2,800 years ago . . . in Greek . . . burnished with a Reidsville accent.

Once I was beyond crying about poor robin, I cut my teeth on Mother Goose, of course, and an all-time favorite, The Big Golden Book of Poetry, an anthology compiled by the publishers of the Little Golden Books, distributed, by and large, in grocery stores. Recently they’ve enjoyed a resurgence among boomers as coffee table tomes with ironic titles, such as Everything I Need to Know, I Learned from a Little Golden Book, and similar ones about love, family and so on, each no doubt racking up enough sales to put the gold in Golden. The poetry anthology is no exception: Out of print, a used edition lists for $164 on Amazon. But its content, as Mastercard would say? Priceless.

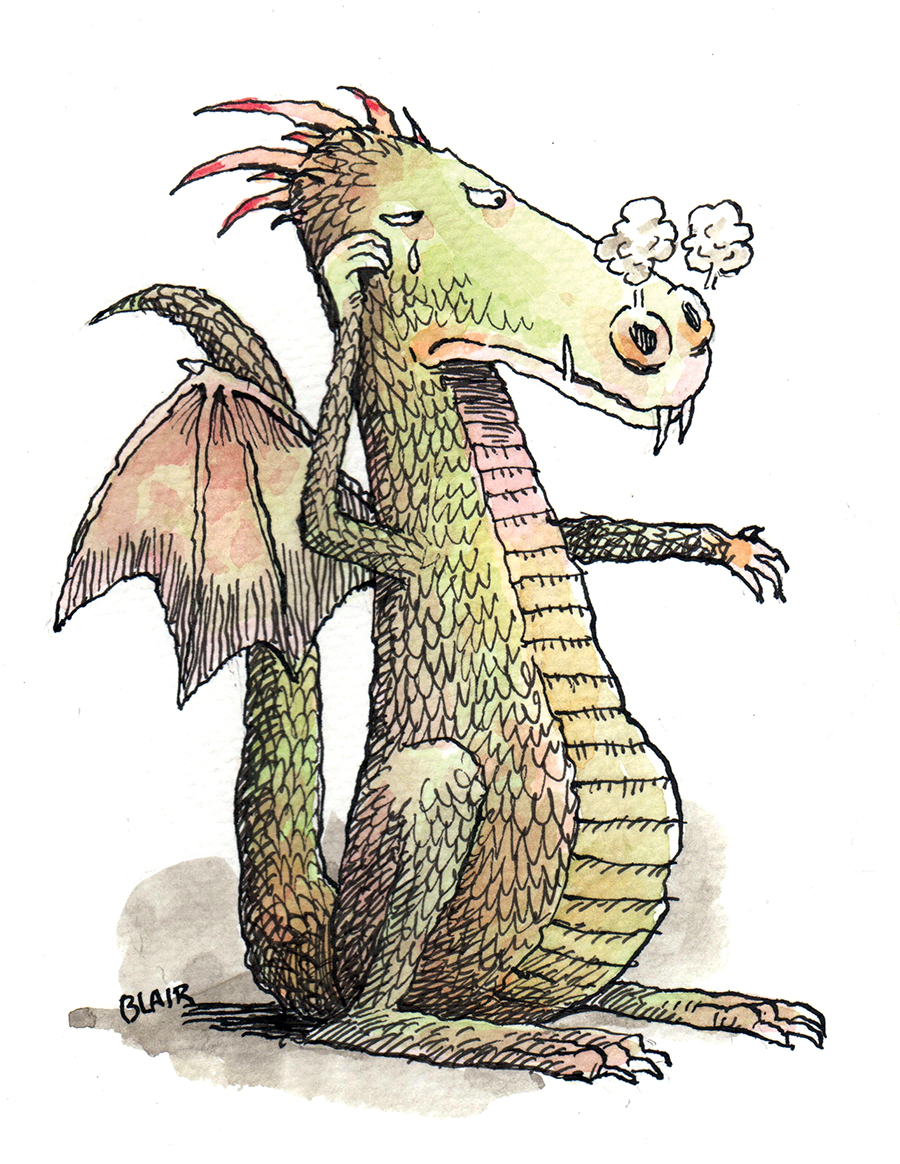

Among the book’s heavily illustrated pages are long poems, such as “Wynken, Blynken, and Nod,” Edward Lear’s “The Owl and the Pussy-Cat” and small ones like “Sally and Manda.” (Two “little lizards,” FYI, “Who gobble up flies in their two little gizzards.”) There are poems by well-known children’s authors — Robert Louis Stevenson, Kate Greenaway, Rachel Field — and anonymous ones, too. Poems about nature, animals, taxis, shoes, country fairs, games of make-believe. And one I loved to read aloud, a 14-stanza opus by Ogden Nash, “The Tale of Custard, the Dragon.” In a nutshell, it’s the story of Belinda, a little girl who “lives in a little white house,/ With a little black kitten [Ink] and a little gray mouse [Blink],/ And a little yellow dog [Mustard],/and a little red wagon, /And a realio, trulio, little pet dragon [Custard].” Nash goes on to explain that “Belinda is as brave as a barrel full of bears,/And Ink and Blink chase lions down the stairs.” Mustard? “Sharp as a tiger in a rage.” Custard? Not so much. He keeps “[crying] for a cage.” Until a home invasion – from a pirate, with (trigger warning for the hypersensitive) “pistol in his left hand, pistol in his right,/And he held in his teeth, a cutlass bright.” Everyone is paralyzed with fear except Custard who — spoiler alert! — gobbles up the pirate, gains newfound respect from his housemates, but still cries for a cage. The end. Kind of a yawner when told in prose. But in poetry it packs a punch.

However silly — OK, childish; guilty as charged — Nash’s verse stood me in good stead by the time I was steeped in lit crit in college, identifying rhyme schemes of Italian and Shakespearean sonnets, or learning how The Bard used rhyming couplets as a signal, a trigger warning, if you will. I came to appreciate the poet’s craft — including Broadway “poets” Cole Porter or Alan Jay Lerner — of expressing emotion and soul-searching within strict rhyming structures, like French poet Paul Verlaine’s phonic experimentation, “les sanglots longs, des violons, de l’autonne/Blessent mon coeur d’une langueur monotone.” Never mind its meaning (unless you prefer an irreverent British cartoonist’s take that the poem is about “a leaf falling on a pile of dogshit”), the point is the music in the sounds of the words.

So what the hell happened? Once I got to studying — excuse me, “explicating” — non-rhyming poetry, I was a little lost. Though, one of my sister’s boyfriends had a solution as irreverent as that British cartoonist’s: “Just interpret everything as man’s alienation in the modern world,” he advised. But I was the one who felt alienated. And still do, especially when I turn on the radio. Sorry, but Taylor Swift moaning about how some man done her wrong ohhhhooooowhoooaahhhh. Yeaaaaaaaah. Unnnhhhh-huunnnh are words pathetic compared to Cole’s poetic, “You’re romance/You’re the steppes of Russia/You’re the pants / On a Roxy usher.”

I guess that’s why I’m the bottom, and Taylor’s in the Top 10. Like poor old Custard the Dragon, crying for his cage, little ol’ Nancy O., looking back toward long ago, realio, trulio, longs for rhymes on the radio, if not on the page. OH

Meantime, she finds solace in editing the poetic prose of O.Henry’s scribes.