Rebirth of a Legend

As historic Gillespie Golf Course celebrates its seventy-fifth birthday,

an important piece of Greensboro’s past reclaims its glory —

and the First Tee of the Triad finds the perfect home

By Jim dodson

After work on a recent warm Wednesday afternoon, I dropped in on the Gillespie Golf Course to play a golf course I’d been meaning to play for at least four decades.

Even if I weren’t a son of Greensboro and a former golf editor, the visit filled a major gap in my professional vita and was long overdue because, simply put, I can trace my origins in the game to this sweet little gem of a public course in the midst of celebrating its seventy-fifth anniversary and leading a splendid revival that’s transforming young lives across the Gate City through the vision of the First Tee of the Triad, the Joseph Bryan Foundation and the Wyndham Championship.

Sometime around 1942 my father — then a young ad salesman and occasional aviation columnist for the Greensboro Daily News — played his first round of golf on the recently competed Gillespie Park public golf course. His interest in the game clearly began at Gillespie but took deep root while stationed in Britain near Lytham & St Anne’s Golf Club during the Second World War.

His love of public golf courses clearly influenced his decision decades later to join popular, semi-private Green Valley Golf Club instead of the city’s three outstanding private courses — Sedgefield, Greensboro Country Club and Starmount. Clear in my head is the memory of passing Gillespie sometime in the early 1980s and hearing him remark with unmistakable nostalgia: “What a wonderful golf course that used to be, once upon a time. Gillespie’s where I started, you know.”

Designed by one of the game’s legendary course architects, Perry Maxwell, who had a hand in shaping Augusta National and designed or remodeled more than a hundred American golf courses including Winston-Salem’s Old Town and Reynolds Park, Gillespie was funded and built by the federal Work Projects Administration on a rolling piece of land once owned by the family of Revolutionary War Col. Daniel Gillespie, one of the city’s founders, who fought for independence at the battles of Alamance and Guilford Courthouse. No records indicate if Col. Gillespie had any familiarity with golf, but his ancestors surely did, since they hailed from the Scottish highlands.’

Witness to the course’s creation was a kid growing up at 1907 Asheboro Street (now Martin Luther King Boulevard) directly across the street from the work site. His name was Jim Melvin, and he would become one of the city’s most dynamic mayors.

“I remember watching the crews working with drag pans and horse teams,” he remembers. “That really aroused my first interest in golf. And by the time I was in junior high school I’d wandered over there and gotten myself a job caddying for two dollars a round. It was a beautiful 18-hole golf course, such a fine layout that the city amateur championship was always conducted there. The pro was Ernie Edwards, who later went on to Starmount Country Club and played a key role many years later in saving Gillespie after it fell on hard times.”

At its height of popularity in the early 1950s, according to Melvin and others who hold it dear, Gillespie Park — as some called it in those days — was one of the busiest golf courses in the Triad. “It was very popular, always busy, a real gem of a place that matched up well to our three private country clubs in town,” Melvin adds. “There was really only one glaring problem. It was a segregated golf course for whites only.”

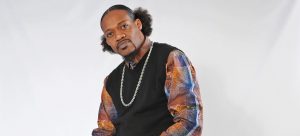

On December 7, 1955, the same week the Montgomery bus boycott was launched in the wake of Rosa Parks’ defiance of segregation laws in Alabama, a Greensboro civil rights activist and local dentist named Dr. George Simkins decided to change that situation.

Simkins and five African-American friends showed up at the course aiming to desegregate the facility. Peacefully demanding their right to play, they put down their 75-cent greens fees and teed off despite the objections of the manager, who advised them that Gillespie was a “private course for members only.”

The six were later arrested for simple trespassing. Two months later, Simkins and the others were convicted of trespassing and fined $15 plus court costs. In a second trial, which was ordered because the original arrest warrants had been altered to describe Gillespie as a “club leased by the city” rather than a “public course,” prompting a middle district judge from North Wilkesboro to issue a declaratory judgment in favor of the “Greensboro Six,” calling the city’s “so-called lease” as a private facility invalid.

In October 1956, while the initial trespass case was still working its way through state courts on appeal, Dr. Simkins filed suit in the U.S. District Court for the Middle District of North Carolina against the City of Greensboro for racial discrimination in maintaining a public golf course for white citizens only. Simkins et al. v. Greensboro was filed by Dr. Simkins as head of the local chapter of the NAACP. He was joined by nine others, including the original five golfers who had been with him in December 1955. On March 20, 1957, the courts ruled in favor of Simkins, stating in the opinion that the City of Greensboro could not escape its legal duties to provide equal privileges to all citizens to enjoy city functions. The case was immediately appealed to the Fourth Circuit Court of Appeals, which affirmed the District Court’s ruling and ordered the city to discontinue operating the course on a segregated basis.

Eventually, Simkins’ suit even found its way to the U.S. Supreme Court where, missing key relevant facts from its brief, the high court ruled against the plaintiffs by a 5-4 margin. A strong dissent by Chief Justice Earl Warren, however, prompted North Carolina Governor Luther Hodges to commute the sentences of the Greensboro Six.

By then, Gillespie was almost history. Two weeks before the Middle District judge issued his favorable ruling, Gillespie’s historic clubhouse — the original farmhouse belonging to the Gillespie family — mysteriously burned. A short time later, the City Council voted to go out of the recreation business and shuttered the facility, soon selling off nine of the holes.

“It was a pivotal moment in the history of this city,” says Melvin. “Not only was it a symbol of our struggles to come to terms with race and inequality in our city, but we nearly lost a great asset to Greensboro.” He points out that it took another seven years and a strong public backlash for a newly elected City Council to reopen (in the wake of the famous Woolworth sit-in) Gillespie Golf Course as a public nine-hole facility. That happened in December 1962.

George Simkins went on to lead successful desegregation campaigns against Cone Hospital and Wachovia Bank. He passed away in November 2001.

“This city owes George and his friends a great deal of gratitude for his foresight and their courage,” says the former mayor, whose stewardship of the Bryan Foundation spearheaded a major revival of Gillespie five years ago.

Funding from the Foundation allowed Greensboro-based designer Chris Spence to restore the golf course and create a new practice area and short course. With additional funding from the Wyndham Championship and other corporate partners, a complete renovation of an existing storage structure on the site became the new home of the First Tee of the Triad and eventually a teaching school for acclaimed golf instructor Kelly Phillips.

“Along with Winston Lake (in Forsyth County), Gillespie has become one of our two flagship First Tee facilities,” says Executive Director Mike Barber. “We started in 2011 with 300 kids across the region. But today we serve more than 1,500 a year in sixteen different locations. We have camps as far away as Statesville and Salisbury. Having a world class facility, like Gillespie not only attracts young golfers of every race and socio-economic nature to the facility but sends a wonderful message about fair play and character formation — and allows us to teach the core principles of First Tee to an eager new generation. Head pro Bob Brooks and his staff have made the place very special and the welcoming spirit very genuine. We believe it already is having a very positive impact on the surrounding community.”

“We couldn’t be prouder of the role we’ve played in the revival of Gillespie,” agrees Wyndham Tournament Director Mark Brazil. “When you go out there and see people of all races playing the course and some of the most promising young players in the region working with Kelly Phillips or just working on their games on the practice range, well, it gives you a good feeling about what golf can do in a young person’s life.”

“Many hands have gone into the revival of Gillespie, ” adds Melvin, who notes that the same South Carolina sculptor who created the handsome bronze statue of the late Joe Bryan that stands near the entrance to Bryan Park recently completed work on a similar bronze statue of George Simkins.

“George is really Greensboro’s Martin Luther King,” he adds. “Honoring him is long overdue.”

As was my first round on the Gillespie Golf Course. Happy to report, I was delighted by what I found. The former golf editor in me was pleased by the beautiful condition of the holes and impressed by the thoughtful design and classic traits of the layout. The remarkably modest green fees make Gillespie Golf an experience everyone can enjoy.

Even happier to report, a city landmark that was very nearly lost has come full circle, making the Greensboro kid in me feel like I’d finally come home. OH