The near-miss glory of the nation’s first regional sports franchise

By Bill Case

Unbeknownst to all but the closest insiders, professional basketball’s 2-year-old upstart, the American Basketball Association (ABA), was teetering on the verge of collapse in December, 1968, when its commissioner, George Mikan, called an emergency meeting of the league’s executive board in Minneapolis. Awash in a sea of red ink, the owner of the Houston Mavericks had advised Mikan that his team was about to shut down. Reading the tea leaves, the Denver Rockets’ owner indicated that if the Mavericks folded, the Rockets would follow suit. It was apparent to Mikan and the board that the demise of one, let alone two, of the ABA’s 11 teams could have a domino effect on the other franchises that would rapidly lead to the demise of the league and its signature red, white and blue basketball.

Given that the league was barely clinging to life, a second matter on the board’s Minneapolis agenda may have appeared as an afterthought. Several North Carolinian buddies hell-bent on acquiring an ABA expansion team for their home state had formed the Southern Sports Corporation (SSC) and requested that the ABA board grant them an audience. The SSC group, headed by 35-year-old Jim Gardner — an early investor in the Hardee’s hamburger chain and a U.S. Congressman — flew to Minneapolis to make their pitch. Prior to the group’s arrival, the ABA’s board members hatched a scheme calculated to use the SSC overture as a lifeline.

The first step of the plan was to betray nothing to the North Carolinian businessmen concerning the ABA’s existential crisis, which explains why the board listened with feigned disinterest to Gardner’s presentation. Referencing an October, 1968, Sports Illustrated article by Frank Deford touting the untried notion of a regional pro team playing in multiple arenas, Gardner proposed that the Cougars would play home games in Greensboro, Charlotte and Raleigh. Hoops-mad North Carolina, lacking a dominant major city (Charlotte was less than one-half its current size), would be the ideal locale for a far-flung basketball franchise, he argued, particularly since no major league team in any sport called the state home.

The Indiana Pacers’ first co-owner, Dick Tinkham, was among the owners listening to this presentation. “They were trying to sell us on North Carolina and were worried we wouldn’t take them,” Tinkham told Terry Pluto in that writer’s wonderful ABA history, Loose Balls. “Meanwhile we would have thought the North Pole was a great spot for an ABA franchise if there was an Eskimo who could buy one.”

Tinkham coolly replied to Gardner that, “the price for an expansion team is $500,000, but there is a way you can get into the league for less than that. You can buy the Houston franchise for $350,000 if you agree to finish out the season down there. Then you can move it to North Carolina.” It was a well-orchestrated bluff. Given the league’s predicament, SSC probably could have acquired the Mavericks for next to nothing. But SSC accepted the league’s offer. The cash infusion into league coffers coupled with the salvaging of the Houston franchise probably saved the ABA from extinction.

After the woeful Mavericks’ final home game in Houston, played before an unenthusiastic crowd of 89 spectators, the Cougars opened for business. The team located its primary office in Greensboro where it would play 25 games in the Coliseum. The balance of the home schedule would be contested at Raleigh’s much smaller Dorton Arena and Charlotte’s Coliseum. Virtually everyone associated with the Cougars opted to live in Greensboro.

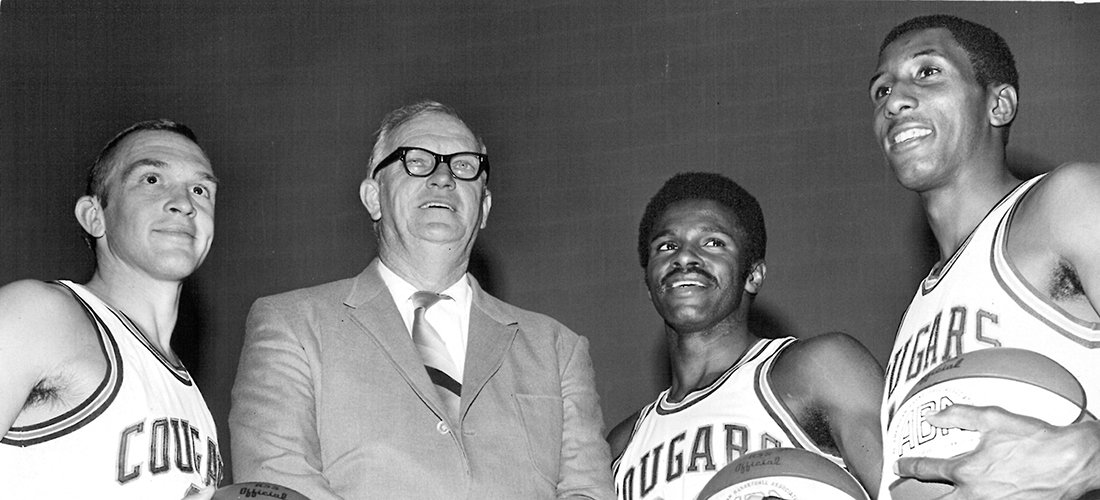

Seeking a colorful personality to lead the team, Gardner tapped the legendary and peripatetic former Wake Forest coach Horace Albert “Bones” McKinney to be the Cougars’ first head coach. During his tenure at Wake, Bones had received so many technical fouls for charging referees that he

finally decided to limit his forays onto the court by seatbelting himself to the Wake Forest bench.

Once, Bones was tossed out of a contest after he was unable to decide whether the ref was a thief or incompetent. So he called him both. Taking umbrage at his ejection, Bones demanded an explanation for being given the heave-ho. “Because you called me a thief,” responded the referee.

“Oh my goodness, no indeed!” remonstrated Bones. “I gave you a choice.”

To maximize the Cougars’ local appeal, Gardner and then general manager, Don DeJardin jettisoned most of the Mavericks’ players and loaded the team with ex-college stars from the home state. Doug Moe, and Bill Bunting from UNC, high-scoring Bob Verga from Duke, George Lehman from Campbell College, and hustling Gene Littles from High Point College became Cougars. Clemson’s Randy Mahaffey was also added to the roster, providing a rooting interest for South Carolinians.

The Cougars relentlessly courted “Pistol Pete” Maravich, hoping to land the LSU All-American following the 1970 draft. But Maravich signed with the NBA’s Atlanta Hawks.

Gardner’s long-range business plan (and that of every ABA owner) was to force a merger with the NBA. The NBA possessed a national television contract and a well-established network of established teams and stars. Gardner reasoned that the only way to give the new league leverage in merger discussions was to punch its more established competitor in the face. He started by courting one of the NBA’s biggest stars, the Philadelphia 76ers’ Billy Cunningham. After six years in the NBA and a third-place finish in the league’s MVP balloting, “Billy C.” was earning a paltry $40,000 a year. Gardner offered Billy a 2-year deal for $200,000 annually — five times his 76ers’ salary. Billy accepted the Cougars’ offer in August, 1969. “I kept thinking about all that money,” recalls the UNC alum. “I knew I wasn’t going to play forever and it was time to make it while I could.”

But due to the terms of his contract with Philadelphia, Cunningham could not take the floor for the Cougars until the ’72–’73 season. Given the Cougars’ upcoming struggles during their first three seasons, the club’s interminable wait for the services of the “Kangaroo Kid” — subsequently named one of the top 50 pro basketball players of all time — must have seemed an eternity.

When George Mikan resigned as head of the ABA in 1969, Jim Gardner became interim commissioner even though he was a team owner. The feisty Gardner authorized aggressive combat against the NBA on all fronts, even luring away that league’s best referees. His aggressiveness set the stage for the Denver Rockets’ signing of University of Detroit underclassman Spencer Haywood as a “hardship case” in defiance of the NCAA’s “4-year rule.” This challenge to the status quo ignited a firestorm of criticism engulfing the entire ABA. But Gardner’s hardball maneuvers failed to lead to fruitful merger discussions. Instead, the angry NBA owners dug in their heels and, for the moment, spurned further negotiations. When NBA star Oscar Robertson filed a federal lawsuit seeking to prevent any prospective merger because it would unfairly eliminate competition for players’ services, hopes that the two leagues would come together drifted away.

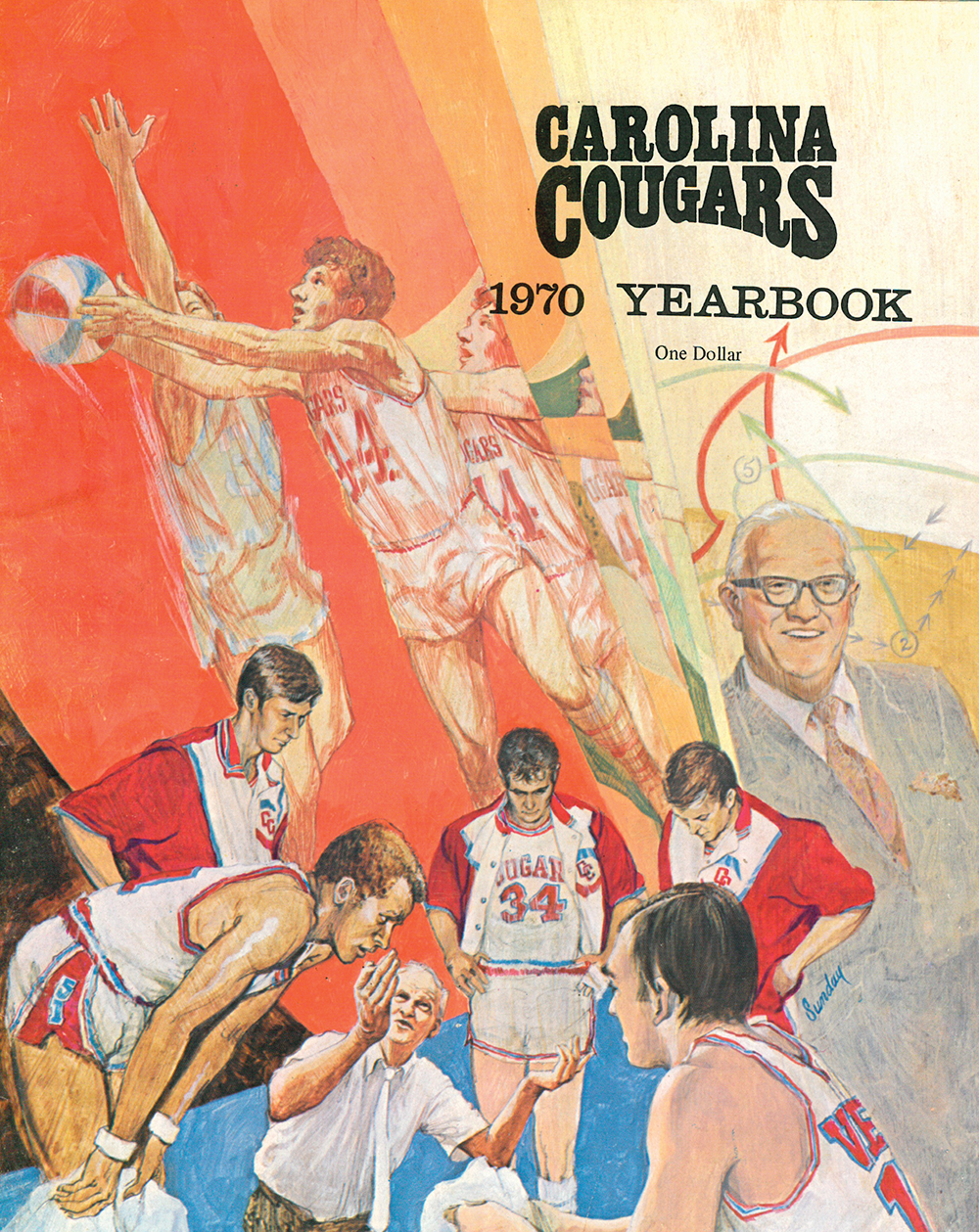

The Cougars’ first year on the court proved to be moderately successful. Bones McKinney coached the team to a respectable 42–42 record in ’69–’70. The ABA was the first league to employ the 3-point shot — now a staple at all levels of basketball — and the Cougars’ sharpshooting guard, Bob Verga, took full advantage of the rule, averaging 27.5 points per game. Bruising forward Doug Moe took care of rebounding and provided relentless defense. The team squeaked into the playoffs, but their appearance was brief as the eventual champion, the Indiana Pacers, swept the Cougars in four straight.

The Cougars’ average attendance of 6,051 — better than many NBA franchises — placed it firmly in the ABA’s top tier. In his January, 1970, Sports Illustrated article entitled “My Baby is Called the Kahlahnah Koogahs,” writer Frank Deford expressed his delight with the progress of a team to which he had helped give birth. A jubilant Deford gloated that the Cougars, the first regional sports franchise in history, had “enjoyed such an auspicious debut that their example is bound to cause repercussions throughout the whole of professional sport. . . . Last year I blew all this smoke as a dreamy theorist. Now I am a hard headed advocate. I have seen Carolina, and it works.”

But notwithstanding Deford’s raves, a couple of cracks in the Carolina Cougars’ foundation were surfacing. Air travel to the other ABA cities had proven to be an ordeal. Bill Hass, who covered the Cougars for the Greensboro Record and the Greensboro Daily News, and continued as a sports writer for the merged News & Record until he retired in 2006, recollects that flying by Piedmont Airlines to an away game (teams flew commercially then) against the Kentucky Colonels in Louisville, less than 500 miles distance, called for three separate airport landings. The return flight to Greensboro required four. Logistics for flights to more distant cities normally necessitated at least two and often three layovers. With home games in three cities, the players often bussed from Greensboro to Raleigh and Charlotte. Play at the latter two venues felt like road games.

Moreover, the need to have office and marketing presences in all three cities hampered the team’s bottom line. And attendance in Greensboro far outstripped that of the other two cities, particularly Raleigh, where crowds averaged under 3,000 in Dorton Arena, a venue often employed for livestock shows.

With no end in sight to the costly conflict with the NBA, Gardner and SSC sold the team in October, 1970, after less than two years of ownership.

Carolina’s new owner was brusque New Yorker Tedd Munchak. His fortune was derived from the carpeting empire he built from scratch in Atlanta. After Don DeJardin left to work in the 76ers’ front office, Munchak hired

former NBA commissioner’s assistant Carl Scheer to be the Cougars’ new general manager. Scheer had a strong Greensboro connection, having graduated from Guilford College and practiced law in the city with his father.

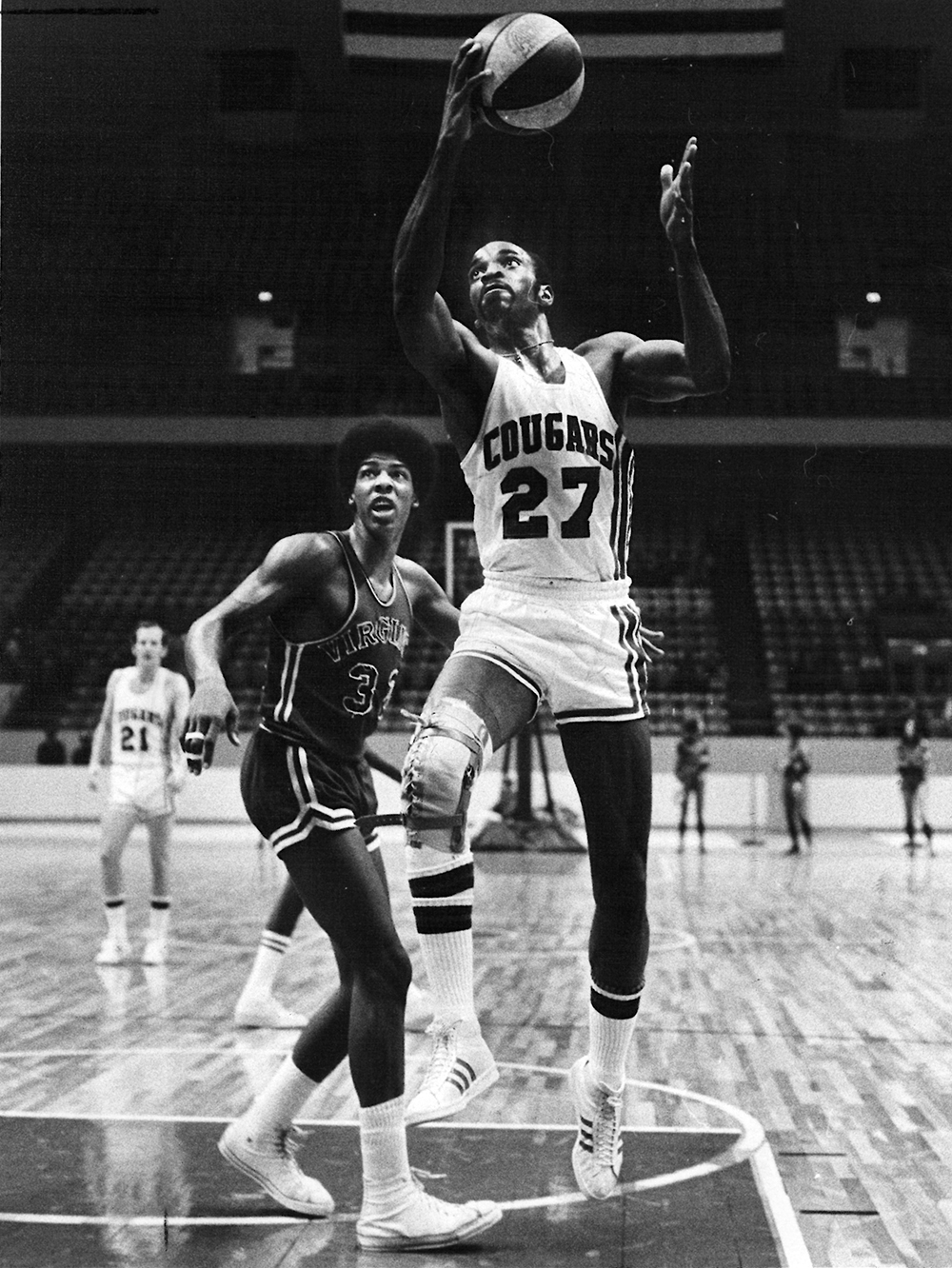

Munchak was willing to spend money to improve the Cougars. Handsome former Tar Heel Larry Miller joined the team. The blue-eyed sharpshooter, given the sobriquet “Lochinvar in Lowcuts,” was a heartthrob among female rooters. And the Cougars enticed Atlanta’s all-pro forward “Jumping Joe” Caldwell to ink a contract, paying in excess of $1 million dollars over five years. Though Caldwell’s signing constituted a victory over the NBA, the heavy financial obligation coupled with the team’s commitment to Cunningham, could not be reconciled with the Cougars’ bottom line. But, as Carl Scheer observes, “If we were going to jump off the cliff, we were going to jump off the cliff together [with the NBA].”

Caldwell turned out to be a mixed blessing for the Cougars. While unquestionably a great defensive forward with scoring punch, his play suffered when he was upset — and he was upset during much of his time with the Cougars. Teammate Gene Littles recollected that Caldwell “complained that we didn’t stay in the top-of-the-line hotels like the Hyatts. I always thought the places we stayed in were fine, and no one else but Joe complained.” In fact, Littles told Pluto, “He didn’t like the airplanes, the arena — he didn’t like much of anything, because it wasn’t the NBA.”

Lenox Rawlings, then a reporter with the Greensboro Daily News, liked Caldwell well enough but considered him a complex character. “You thought you had him figured out,” muses Rawlings. “Then the next day you realized you didn’t.”

Caldwell’s presence on the ’70–’71 squad did not lead to more victories. Team MVP Moe had been traded to the Virginia Squires, and his tenacious presence was sorely missed. The Cougars finished at the bottom of their division. Bones McKinney resigned at midseason after compiling a 17–25 record. Bones’ assistant Jerry Steele assumed command and did no better, coaching the team to another 17–25 mark in the second half.

Though the Cougars’ play was forgettable, the season was not without its memorable, if bizarre moments. On November 6, the Cougars hosted the Pittsburgh Condors at Raleigh’s Dorton Arena. Late in the first half, Condor journeyman Charlie “The Helicopter” Hentz, a 6’ 5” forward, leaped high to unleash a powerful dunk. In so doing, The Helicopter tore the rim down. The glass backboard shattered, with shards flying everywhere, including into some of the players’ fashionable Afros. Referee John Vanak thought for a moment “the whole arena was coming down.” A lengthy delay to clean up the debris and find a replacement backboard ensued. The only one available was of the ancient hardwood variety. After it was mounted, the spectators seated behind the wooden backboard were moved elsewhere so they could see, and the game resumed. Late in the second half, Hentz astoundingly shattered the remaining glass backboard with another tomahawk slam. Reportedly, The Helicopter smiled broadly at his handiwork. Basketball’s only “double shatter” prematurely ended the game with the Cougars winning.

Then, eight days later following an earlier cattle show, a huge swarm of flies and other insects, greeted the Cougars and Indiana Pacers at Dorton. Most of the fans fled the arena, but the teams endured this “Lord of the Flies” nightmare till game’s end.

Hoping to galvanize the underperforming Cougars, Munchak and Scheer hired newly retired NBA veteran Tom Meschery to coach the ’71–’72 squad. Good enough for his number 14 to be retired by the Warriors franchise, Tom spent the bulk of his 10-year career playing alongside Wilt Chamberlain. A bit of a nonconformist with a literary bent, Meschery had written a book of poetry and intended pursuing an unconventional post-NBA path by joining the Peace Corps to coach basketball in Venezuela. But that plan fizzled so Meschery was receptive to giving professional coaching a try when Scheer called on him in August, 1971. He signed for $38,000. “It sounded like the Cougars were going to be a good team,” said Meschery in Pluto’s book, Loose Balls. He went on to say that he looked forward to the job because the team, “had Joe Caldwell and had just signed Jim McDaniels [who had just led Western Kentucky to the NCAA final four]. I’d played against Joe and had a lot of respect for him. McDaniels was considered a real promising rookie. And the following year, Billy Cunningham was coming over once his contract was up.” Meschery also looked forward to coaching hard-working Cougars Gene Littles, Wayne Hightower, Wendell Ladner, Ted McClain, Tom Owens, and Ed Manning (the son of a sharecropper and father of future star Danny Manning).

But Meschery’s hopes were quickly dashed. Joe Caldwell afforded the new coach little respect. Jumping Joe (also known as Pogo Joe) complained to Munchak that “we’ll never win a game with this guy [Meschery] on the bench.” Caldwell’s barrage of complaints, some racial in nature, were an ongoing source of dissension, and the team’s play reflected it. Relations with Joe became so toxic that Scheer considered peddling Caldwell back to the Hawks.

But the grief caused by Caldwell paled compared to the brouhaha generated by prized rookie McDaniels, a high scoring center who, Meschery discovered to his dismay, “couldn’t play a lick of defense.” To compound the situation, McDaniels decided he’d rather be playing for the NBA’s Seattle Supersonics and began claiming that the Cougars had breached his contract. Ultimately, he failed to show up for a February game in Louisville. “Here I am a first year coach,” reflected Meschery,” and my star rookie [averaging 26 points a game] is trying to get out of his contract after four months — and it’s a 25 year contract [for $1.5 million], mind you!”

Among the bizarre assertions McDaniels’ L.A. agent Al Ross made to justify his claim of a Cougar breach of contract was that the team had supplied a car with a standard steering wheel instead of one that tilted. To continue playing with the Cougars, Ross demanded that the Cougars spread McDaniels’ $1.5 million over 15 years instead of 25. Ross also asked for an immediate $50,000 bonus “for the aggravation of living in North Carolina.”

Beset by legal fees, Munchak came to terms with Seattle, letting his headache of a player go to the Sonics in exchange for $400,000. In the end, McDaniels never lived up to the potential he showed with the Cougars. Two years after his jump, he was playing ball in Italy. But the litigation had taken its toll. Prior to the settlement, the Cougars became entangled in five lawsuits involving McDaniels filed as far away as L.A. and Seattle. Indeed, the Cougars proved to be a trial lawyer’s dream during their short existence. Other litigation included included:

• A suit between the Cougars and 76ers related to their respective rights to the services of Billy Cunningham;

• A claim of breach by Cunningham against the Cougars;

• An attempt by the NBA’s Hawks to stop Joe Caldwell from playing with Carolina.

Long after the Cougars closed up shop, Caldwell would emerge victorious in a decade-long battle with Munchak over the player’s pension. Moreover, the Cougars had to ante their proportionate share of legal fees arising from the ABA’s antitrust case against the NBA and defending the league in the Oscar Robertson suit.

What’s more, the team continued to flounder. Team MVP Larry Miller was a bright spot, averaging 18.4 points — a solid season by a solid player. But in one memorable March game at the Greensboro Coliseum against the Memphis Pros, Miller elevated his game to the superstar level. He started the game on fire, canning shots from all over. Sensing something special was happening, his teammates, including Joe Caldwell, began looking for Miller on every offensive possession. Pogo Joe once recalled that, “when Larry got hot, I made sure the ball stayed in his hands. “Miller scored 67 points that night, the most ever in ABA history.

But triumph would turn to tragedy. Two days later, Miller’s lakeside house near Greensboro burned to the ground. A lightning strike apparently caused the fire. Miller barely escaped with his life, badly gashing his hand while fleeing the house in his underwear. His two dogs perished in the blaze. After receiving 11 stitches at the hospital, Larry still managed to catch a late plane to New York for the following night’s game with the Nets.

Tom Meschery left after the season (with a record of 35–49) and became immersed in the literary world. He’s still writing poetry and about to publish his first novel. Meschery confides that his year in Carolina made him realize he was not cut out for coaching. Might he have thought differently had he been around in ’72–’73 to coach Billy Cunningham whose play would help transform the Cougars into a winner? “Oh, I don’t know,” says the self-effacing poet. “Billy and I would probably have sat around drinking too much beer.”

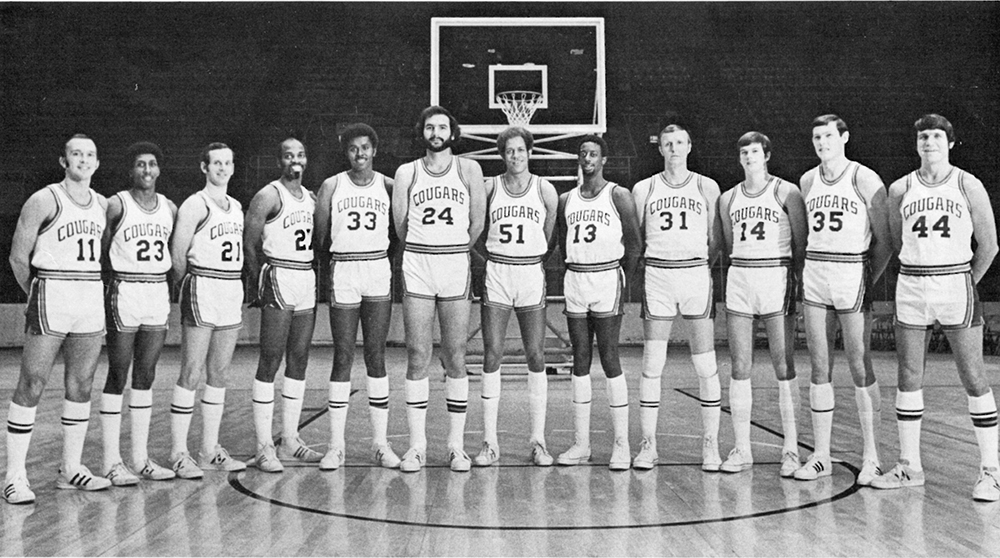

Munchak took a more active role in hiring the next Cougars coach. At the recommendation of the legendary Dean Smith, he chose former ABA all-star guard, 32-year-old Larry Brown. This would be the first of 13 stops in the vagabond Brown’s Hall-of-Fame coaching career. Brown brought along sidekick and former Cougar Doug Moe as his assistant. Knee surgery had ended Moe’s playing career. General manager Scheer acquired two offensive-minded ABA all-star guards, Mack Calvin and Steve “Snapper” Jones. Combining their talents with those of the defensive-oriented Gene Littles and Ted McClain, the Cougars had overnight assembled an impressive group of guards.

And Billy Cunningham finally made the scene. Though he had earlier sought to get out of his contract with the team, he says he had “the time of my life playing for the Cougars.” But there was concern how Joe Caldwell would react to being paired with Billy C., a star whose gifts exceeded even those of the talented Jumping Joe. There were troubles early. On the first day of practice, Doug Moe observed that the sullen Caldwell, a notoriously lackadaisical practice player, was not giving his all. Moe rarely hid his feelings, and he promptly threw Joe out of the practice. “Get your ass outta here,” he ordered. “We only won 35 games last year with you here. We can win that many without you.”

In the aftermath, Carl Scheer tried to unload Caldwell, but the moody forward’s hefty salary rendered him unmarketable, so he remained with the team. Though there were worries that Joe’s difficulties could adversely affect the Cougars, his attitude improved once he noticed that his teammates’ hustling play and Larry Brown’s coaching were helping his own game. Brown had installed a jump-switch pressure defense relying heavily on full court harassment tenaciously applied by his four guards. This tactic resulted in numerous turnovers and easy baskets for Joe and his teammates. Surprisingly, Billy C.’s presence actually benefited Joe’s offense as Caldwell could no longer be double-teamed. And Cunningham was phenomenal, averaging over 24 points and 12 rebounds per game — leading the league in steals. The Kangaroo Kid would be named league MVP over the likes of Julius Erving, Dan Issel, and George McGinnis.

Larry Brown proved an ideal leader. Steve “Snapper” Jones later described what made the coach tick. “Larry’s real talent is his knack of walking into a disaster, bringing order and stability and making players happy,” said. Snapper who passed away recently. “I was traded by Dallas to Carolina, and it was a huge break for me to play with a really good team.” Similarly, Lenox Rawlings viewed Brown, “as the kind of person you wanted to do something for. He had great energy.”

Carolina was finally riding high and Cougar fever attained new heights as attendance at the Greensboro Coliseum approached, at times, its then capacity of 15,000. Among the team’s delighted onlookers was season ticket holder and Daily News managing editor Irwin Smallwood. Smallwood, whose seats were immediately behind the Cougars’ bench, reflects that every person in attendance almost seemed an integral member of the Cougars’ family. Smallwood admits he was not shy in voicing his displeasure with Larry Brown’s substitutions or referees’ bad calls. “Some night I helped Larry coach. Other nights I helped the referees,” chuckles the former editor.

The Cougars stormed to the eastern division title with an ABA best record of 57–27. Carolina mowed down the New York Nets in the first round of the division playoffs, and then squared off against the Kentucky Colonels in the division finals. The Colonels featured perhaps the most dynamic front line in all of basketball. Dan Issel, 6’ 9”, and 7’ 2”’ Artis Gilmore could both score at will and dominate the boards. Lithe Tom Owens was a serviceable center for the Cougars, but the going was tough when he faced the bulk and talent of Kentucky’s two all-pros.

Nevertheless, the Cougars, playing inspired basketball, forced a 3–3 split in games heading into the series finale to be played at home. But where was “home” to be? To the consternation of the entire team, the game was played in Charlotte rather than Greensboro. The Cougars had won all four of their previous playoff games held in the Gate City. Bill Hass recollects the Colonels’ Dan Issel expressed relief that the deciding contest would not be played in front of Greensboro’s boisterous rooters. The Colonels won the finale 107–96, and a disappointing end came to a near-miss dream season for the Cougars. Placating Charlotte and its fans may have come at the expense of the Cougars’ winning the division title. Another “what might have been!”

Despite having finally built a winning team, Munchak was frustrated. Regular season attendance had only slightly exceeded that of the first year, and the numbers in Charlotte had dwindled alarmingly as the season wound down. “I was told and told last year that if we ever had a winner the fans would be here,” the owner griped to Lenox Rawlings. “Where are they?” Increasingly, Munchak verbalized his dissatisfaction with the level of corporate support in Greensboro. Moreover, promoting and paying for club presences in three cities had proven to be an expensive albatross. “We wanted to be everything to everybody,” says Carl Scheer today. Munchak and Scheer toyed with abandoning the regional concept and locating the team full time in either Charlotte or Greensboro. But due to fears that casting any of the cities out in the cold would backfire on the team’s image and branding, the Cougars commenced the ’73–’74 basketball season with no alterations in the three

cities’ home game allocations.

Notwithstanding these business concerns, the Cougars approached the new season with high hopes. All of the team’s key players were returning, and there was optimism that Carolina could capture its first ABA title. But again, fate struck in an unmerciful fashion. Cunningham was sidelined with a serious kidney ailment and sat out most of the season. Though still a competitive team, the Cougars were missing their mojo. The team labored to a 47–37 finish, third place in the east — a full 10 games worse than ’72–’73. An ignominious conclusion to the season took place when the Cougars bowed out with four straight defeats against the Colonels.

Even before the conclusion of the playoffs, Scheer announced that the Cougars would be abandoning the regional concept and would be playing exclusively in Greensboro or Charlotte, “or elsewhere.” And then he added, “We’d like very much to stay in Greensboro.” But when the city rebuffed the Cougars’ request for leniency on lease arrangements at the Coliseum, the team’s days in Greensboro were numbered.

Electing to leave the basketball business, Tedd Munchak turned his attention to finding a buyer. None surfaced from either Charlotte or Greensboro. Disturbed that the Cougars appeared on the verge of vacating North Carolina, Billy C. decided to go back to the 76ers. “Here the Cougars were supposed to be one of the top four teams in terms of gate revenues, not just in the ABA, but all of basketball, and Munchak was getting out,” Cunningham told Pluto. “I decided it was best to go back to the Sixers.”

Munchak, ultimately sold the Cougars for $1 million dollars to two New York-based brothers, Ozzie and Daniel Silna. The brothers decided to move the team to St. Louis, renaming it the Spirits of St. Louis. As a result, there was wholesale turnover. The coaching tandem of Larry Brown and Doug Moe hightailed it to Denver for two years, with Moe returning as the Nuggets’ head coach in ’80–’81, after a 2-year stint with the Antonio Spurs. Carl Scheer, heartsick that the Cougars were leaving his hometown, rebounded to become Denver’s long time general manager. It was Scheer who first conceived of the first slam dunk contest, held in Denver at the 1976 ABA All-Star game. Of the players, only Caldwell, Owens, and Jones became Spirits.

Though the Silnases acquired several promising young players and gave young Bob Costas his first pro announcing job, the team’s performance deteriorated drastically in St. Louis. The Spirits plummeted to a 32–52 record in the 74’–’75 season, and a 35–49 ledger in the final ABA campaign of ’75–’76.

Then merger discussions heated up again. A primary motivation for the rekindling was the NBA’s desire to bring exciting ABA mega-stars like

“Dr. J” Julius Erving, George “Iceman” Gervin and David Thompson into its fold. The two leagues were granted permission by the federal court in the Robertson case to merge provided that players would be permitted to negotiate with other teams once their contracts expired. But it transpired that the NBA would accept only four of the remaining six ABA franchises into its ranks. To the Silnases’ chagrin, St. Louis, along with John Y. Brown’s Kentucky franchise were the odd teams out. The San Antonio, Denver, Indiana and New York franchises were granted admission. However, the NBA expressed its willingness to pay the Silnases and Brown $3.3 million apiece to fold their franchises, thereby allowing the league to disperse Spirits and Colonels players to the remaining teams.

John Y. Brown accepted that offer, but the Silnases had a different arrangement in mind. The brothers proposed that they receive instead $2.2 million cash plus payments going forward each year in the amount of 1/7th of that portion of NBA’s television rights fees being paid to the Rockets, Spurs, Pacers and Nets. The league agreed. At the time, the NBA’s network revenue was very modest and it appeared questionable whether the Silnases had made a smart deal. But with the advent of Larry Bird and Magic Johnson, NBA income from TV skyrocketed, and so did the payments to the Silnases. By 2014, the Silnases had received over $800 million just for agreeing to go out of business in 1976. This transaction was labeled by Forbes magazine as the greatest sports business deal of all time. It is ironic that the only investors to have made significant money out of the Carolina franchise were the ones that moved it, presided over its spiral downward into a losing team and then folded it.

Today, the Gate City is privileged to have the Greensboro Swarm, (affiliated with the Charlotte Hornets), a member of the NBA’s developmental G League, in its midst. But if events had unfolded slightly differently, if fortune had smiled rather than frowned on the ill-fated Carolina Cougars, a basketball team at the game’s highest level might still be playing games here in Greensboro. OH

When he isn’t following the history of the ABA, Bill Case spends his time contributing to O.Henry’s sister magazine, PineStraw.

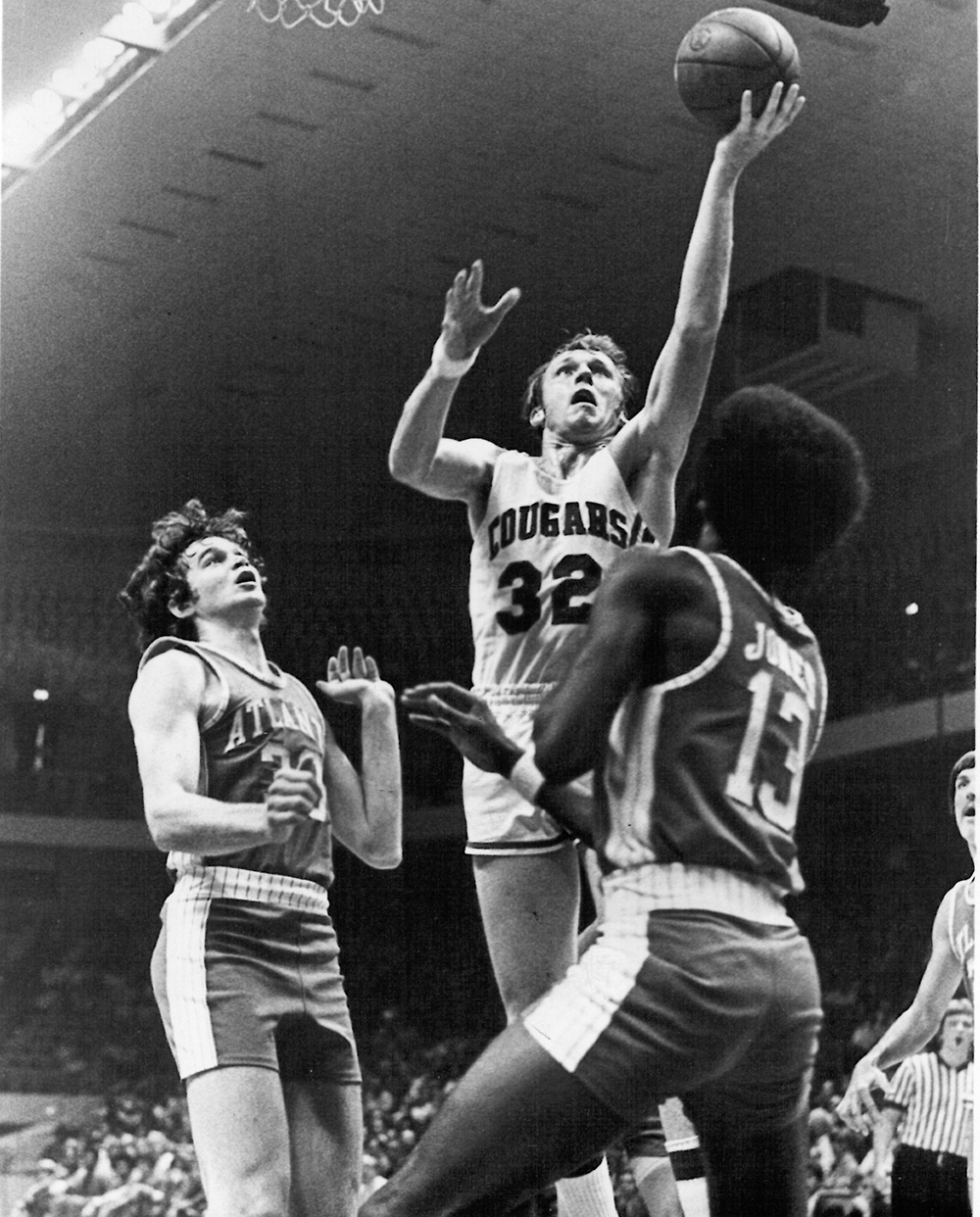

Photographs by News & Record Staff, © News & Record, All Rights Reserved