Designer Larry Richardson pulls straight from nature to color his home magnificent

By Cynthia Adams • Photographs by Amy Freeman

Floral designer Larry Richardson is just as prone to brake for newly-fallen hedge apples he spied along a city street as he is to pluck a seed pod and incorporate it into fall décor. Varying living and dried elements, he creates a moody tableau that resembles a Dutch still life, where you might find a ripened piece of fruit or cut pomegranate or exotica. Richardson avidly shops Mother Nature as freely as he does cultivated plants in his greenhouse. Summer’s end brings its rewards, Richardson says. But he considers autumn a welcome prelude — a time of harvest and found beauty.

As one season opens the door onto the next, each of us yearns to welcome Nature’s changing mood and shifting palette into our own homes. Richardson, with two floral shops, a greenhouse and years of experience, is an expert at condensing the landscape’s kaleidoscopic transformation into stunning arrangements. In late September, he was way too busy to sit down for a long interview, but he did take the time to share some hints and creative insights into how he does what he does so well.

Richardson recommends opening the eye to what is beautiful in the “quiet season” as vivid summer hues dim to duller shades of gold. He appreciates the restful muting of the natural color palette before the extravagant riot of hues and tones homeowners gravitate toward in the winter holidays. As an example, Richardson stands before a display he created, a sumptuous mix of intensities in plants and objects: amethyst, cinnamon, terra cotta and golden browns.

An orange bromeliad blooms midst ferns and angel-wing begonias, not to mention a cornucopia of gourds, dusky pumpkins, golden and green foliage, ornamental peppers, flowers, fruit, nuts, ornamental seed pods and branches of bittersweet. Many of those colors are drawn from a real still life hung nearby.

Think like a painter, he teaches. Contrast and surprise are key to a pleasing fall arrangement.

“When you think of fall, you think of cooler temperatures,” he says on an afternoon at the greenhouse, where workers are unpacking boxes and the interior of his showrooms are filling with fall-themed organics and an assortment of decorative objects. It is one of those rare September days, cool yet not cold, after record-breaking weeks of scorching heat.

By autumn, we face the reality of months of cold ahead, Richardson says. “The colors warm up. You want to feel the warmth,” he smiles, adding, “You want to be wrapped by the beauty, so that you remember to appreciate each day.”

In September, everyone is thinking autumn and autumnal colors, he says. His job is to help customers find a creative direction employing a mix of the vintage and natural world.

Yet in truth, watching Richardson as customers dart in and out, asking about plants and recommendations, autumn doesn’t seem as quiet as he suggests. The fall season looks more like a qualifying race for an all-out marathon, one that will occupy him, his partner, Clark Goodin, and the staff for months to come.

Richardson’s two businesses, Plants and Answers: The Big Greenhouse on Spring Garden Street and a floral shop downtown send him hunting and gathering new combinations of natural components, plants and organic finds each fall into the end of the year.

Any of us can do the same, no matter our budget, he insists.

Richardson admires millennials’ fondness for plants — noting a heightened interest in the unusual (from philodendron to air plants). He likes what he terms experimentality, whether in choosing a plant, composing a planter or preparing a table for a special meal.

Creativity is free, he stresses. To illustrate, he pops an ornamental cabbage plant into a tiny bag of water before tucking it into a centerpiece, where it will stay a few days before being transplanted into a planter.

Richardson describes how he decorates at home. Even a creative must seed his creativity.

So, he walks through his house like a visitor, “and I look for wood carved things, natural elements, old gourds, dipper gourds, apple gourds. At home, I will mix in fresh Granny Smith apples and red apples because those types of things will hold for a long time.”

He seeks out an object to inspire.

“I have a tendency to want to bring together lots of different elements. In the fall, I like to bring in natural elements. You may have a piece of pottery you want to bring in, and let that be your inspiration to start,” he suggests.

“Then, I want to make my fall showcase the bounty of the end of the season,” he says. The summer is when you grow things and then in the fall you harvest them. “So, harvest those things, whether they are by the side of the road, or old okra pods, different pieces, like bittersweet, which I harvested outside by the greenhouse.”

Draping bittersweet branches across a display adds tiny explosions of orange to a subdued arrangement.

“It was only branches of green pods yesterday, but it opened overnight to give me the orange that we like.” He will use those branches yearlong, as they dry and colors intensify.

“I like for the outside to flow into what you do decoratively on the inside,” he says. “You use the same color palette, and it keeps growing. I do that at home; you want the outside to be a reflection of what you would imagine is on the inside.”

Richardson says he approaches seasonal decorating methodically — the exterior first. “I have a tendency to do my front door. Then the side and back doors.” As for the front door, it should introduce the foyer and interior concepts for cohesion.

He contemplates decorative accents for mantle and dining room table. Even ordinary work spaces might get embellishment.

“Then, don’t forget the kitchen island,” he reminds.

Late year, Richardson appreciates the impact of orange — not garish orange but a persimmon orange. And blue. (More on the blue later, a bit of an obsession.) “I have a tendency to go with orange, reds, and golds . . .” Bright yellows are too intense.

“They command the eye.” He amends, “they demand the eye.”

For the table, Richardson composed an arrangement of fruits, berries, vines, gourds and plants with dark foliage — “anything that’s more natural in the fall.” Then, he placed ornamental peppers in silver wine buckets.

“Branches are good with berries and fruits on them,” he suggests. If you’re entertaining, cut some branches off with the fruit attached. “Look for things you can use from your garden. Or dry hydrangea. Cut those blooms now and hang them upside down, and they will dry and have the fall colors.”

A painting was the inspiration point for another autumnal display.

“Pansies were the start. The ‘wow factor’ was the crabapple branches. Which is what you expect this time of year. And it will (still) be beautiful at Christmas.”

He used pottery pieces, building upon tonalities and textures — from clay to brass and copper.

“If you look, notice the pottery is there giving a grounding,” he says as he explains the display. “I brought in the carved bear pushing the wheel barrow. I had carved owls and used the wooden elements of the bowls.” These he filled with (faux) fruits. “Copper was my inspiration. Then, where I used dark foliage, it looks like velvet.” He points to a velvety, purply-colored leaf — “It’s a Rex begonia.”

Richardson usually avoids standard oranges and greens, even in autumn. Instead, he chose a bromeliad for an unexpected accent. Adding in dried pods to the display summoned a cinnamon color.

“I have a tendency to use the French style and clump things. Rather than spread something throughout an arrangement, clump it. You get much more impact,” he explains. And strive for dimension.

The finishing touch to an arrangement is the bittersweet.

“It gives that air and texture — if you took that away, it would be pretty, but this adds depth to the arrangement.”

Richardson has strewn leaves as if they fell there naturally; there are dried artichoke and cat tails.

He gives emphasis to the center of the table — not even the mantle takes precedence. “Anything else is auxiliary for the table.”

Richardson used a vintage goose tureen as the focal point of the centerpiece. Again, he cleverly tucked small cabbage plants into the display, which can later be transplanted outside.

“I placed brass tureens on the mantle to tie that in,” he explains, along with an elongated planter holding ferns. Indian corn and leaves serve as accents. “I can add berries, add dried bittersweet, and I might tuck in a pear that is fresh. I have a tendency to warm things up (color wise) in the winter, then cool them down in the spring and summer.”

Fall décor can extend into Thanksgiving and beyond, designing everything with that in mind.

“Even the goose on the table can stay till Christmas,” he indicates. “I would introduce more greens and evergreens.”

“Lots of times when I put together the elements of a table-scape, I think about what I want to get out of it. To make life a little easier, I do want to use the goose theme for Christmas as well.”

The table china is a Lenox white pattern rimmed in cobalt blue.

Over the mantle hangs a painting that inspired the arrangement below. An oval antique fish platter, in blue accented with orange, hangs above it.

Paintings are frequently moved, depending upon the season.

“Art can be moved,” he says. “I do that all the time. I change my art depending upon what I’m trying to achieve.” For instance, if he’s entertaining, a painting might take a place of honor in the dining room. Or, “It could be the lighting has changed throughout the year, and makes the art take on a whole different look.”

The buffet is set with serving pieces. Richardson likes to place pieces from his massive blue-and-white porcelain collection.

He marks the moment whether entertaining or not. It’s very French to do this, he explains. “Their lives are built around eating and entertainment. And they pull out the stops for just two.”

So does Richardson. And he enjoys a sense of occasion.

Meanwhile, with autumn giving way to the intensive holiday season, Richardson mans the greenhouse as Goodin runs the florist. He also sells antiques at the Carriage House and the Shoppes on Patterson.

But plants are at the heart of his work.

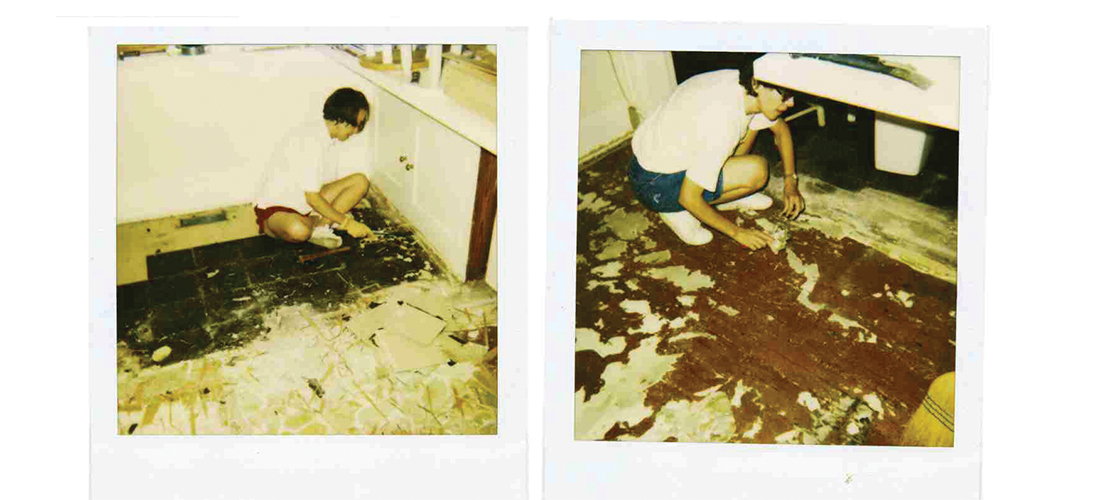

Like many Triad businesses, Richardson got his start at Greensboro’s Super Flea, where he sold plants. (It was also a place where he scouted vintage treasures.)

“It was in July of 1975, the first Super Flea. I started Plants and Answers later that year.” Former teacher Pat Fogleman joined him becoming “my good man Friday. Now she’s much more than an assistant.” He built the greenhouse in 1976.

He told Fogleman that orchids would be good sellers. She fretted they were too expensive for a flea market. He told her buyers would value them if she did. He created combination baskets (“some call them European gardens”) and though she was initially uncertain, Richardson saw that she possessed an eye “and just had to develop it.”

Fogleman is a mainstay at the greenhouse, where she helps customers find the right touch of natural color to warm their home, he says. “She has a following,” he smiles.

Richardson started out thinking he would be an academic; he has so many interests, ranging from botany to antiquities. But he distills all of it down to this: “I love beauty.”

From early autumn till the ball drops on New Year’s Eve, he will be in a mad dash to beautify Triad homes and gardens. He and Goodin will watch Times Square via TV on the third floor of their Sunset Hills home.

The snowdrops and crocus will be nudging their way up, soon to appear. OH

Cynthia Adams is a contributing editor to O.Henry.

Tips for Fall Décor:

• “Go big or go home,” he says when it comes to more appealing pots and container gardens.

• “Go for unusual.” Richardson is not a big fan of chrysantmums, which are ubiquitous.

• Visit garden centers and nurseries and seek out unusual foliage and colors.

• Go organic: get into the woods or your own yard.

• Dry your own flowers.

• Pick up dried pods and plants and use them. Be original and avoid trends: (“Ghost pumpkins are out,” he advises.)