On the fortieth anniversary of his Rug Business, High Point’s Zaki Khalifa shares the story of an American Dream that almost wasn’t

By Maria Johnson • Photograph by Amy Freeman

He came to High Point to visit.

He ended up staying.

That was forty years ago.

In that time, Zaki Khalifa — all 5-foot-10, 167 pounds of him — has become a pillar of the community, widely respected and honored.

He has accepted every business and humanitarian award that the city can bestow.

He has built a successful business, Zaki Oriental Rugs, which claims the largest selection of fine handmade rugs in the United States.

Zaki’s customers dot the globe, but there’s only one place they can buy his rugs: a 100,000 square-foot showroom on South Main Street in High Point.

Zaki has shared the bounty. A native of Pakistan and a naturalized U.S. citizen, he has given his adopted hometown money, time, real estate and, perhaps most important, friendship.

For many of his American friends, he is the only Muslim they know, their go-to guy on all matters Islamic.

They describe him as humble. Kind. Brilliant. A good listener. A man with an open heart and mind.

You can hear the affection in what they call him: Zaki. Just Zaki.

Recently, Zaki, 71, reflected on his life before and after he landed in High Point.

In a soft and measured voice, he spoke plainly, at times bluntly, at times tearfully. He recounted his privileged upbringing in Pakistan, where he witnessed mutual admiration between Christians and Muslims, and his decision, under the influence of a dear friend from High Point, to leave behind a comfortable life for an uphill slog in a different world.

He also talked about the two nonprofit organizations backed by him and his wife, Rashida: an Alamance County health clinic for low-income people; and a foundation that educates and feeds poor children in Pakistan, partly an attempt to keep them from falling in with terrorists and becoming suicide bombers.

Both organizations echo the philanthropic efforts of Zaki’s grandfather, the lifetime president of Pakistan’s largest social welfare organization.

“It’s keeping with the family tradition,” says Zaki.

He was raised by his grandparents, not because his parents couldn’t care for him, but because his paternal grandfather declared it would be so.

Zaki was the first child of a first child, a prized slot in the family hierarchy, and his grandfather decided, even before Zaki was born, that this special grandchild would enter the world in his home and stay there.

Zaki’s mother lived with them, in the bustling city of Lahore, away from Zaki’s father, who worked as a government official in a nearby town. When Zaki was a year old, his grandfather announced that Zaki’s mother could stay or she could return to her husband. She joined her husband. Neither she nor Zaki’s father protested the grandfather’s decree.

“His word was law,” says Zaki. “Granted, my grandfather’s authority was unusual, even for that part of the world, but still grandparents generally have much more say in the life of their grandchildren than they do here in the United States.”

Outside of the family, Zaki’s grandfather’s opinions were equally weighty. He was a prosperous attorney, politically connected. When India won independence from Britain in 1947, two years after Zaki was born, his grandfather represented his homeland at roundtable discussions in England to divide the subcontinent into India and Pakistan. He was elected speaker of the house in Pakistan’s new Parliament. Zaki grew up learning the social graces that came with living among educated and influential people.

“I was taken to the most formal parties hosted by the government in honor of visiting heads of state. I would have a separate invitation in my name,” he says.

His grandfather required Zaki to sit in the gallery of Parliament one day a week and watch him preside from the speaker’s chair. The discipline and civility of the proceedings made a lasting impression on young Zaki.

“One day, when the deputy speaker of the house raised his voice, I remember distinctly that my grandfather warned him to mind his tone. He lowered his tone. A few minutes later when his voice was raised again, my grandfather threw him out. He could not enter again until he gave an unconditional, written apology. Only when it was accepted was he allowed to return — something you don’t see in the world today,” says Zaki.

Zaki’s grandfather was a strict Muslim, schooled from a young age by orthodox scholars. He had memorized the Quran by age 7. But he also studied Christianity and the Western world. He earned a master’s degree in English by age 18, then his father — the director of education in British-ruled India at a time when few native Indians held key government posts — sent him to Cambridge University in England, where he pocketed three more degrees, including Doctor of Law.

Zaki received diverse schooling, too. His grandfather could have sent him to any private school, but he enrolled Zaki in Pakistan’s best public schools, which employed both Muslim and Christian teachers.

Zaki studied for two years at Islamia College, where one dean was Muslim, one Christian.

After Zaki’s grandfather died, his parents sent him to Forman Christian College, which was run by Christian missionaries. The teachers went to lengths to learn more about their Muslim students.

“Most prominent amongst them was my honorable professor of political science, Dr. Carl Wheeless,” says Zaki. “He even went to the villages to see the students’ families. It would be difficult for Americans to imagine how primitive living conditions were in the villages, especially in the ’50s and ’60s, but Dr. Wheeless was happy to visit, even when it involved an overnight stay.”

Sitting on a cloth-covered sofa in his simply furnished office, Zaki reaches for his handkerchief as he talks about his former professors. They did a better job of promoting good relations than any American embassy employee, he says.

“I’m getting emotional because this is starting to run before me like a movie,” he says. “These educators commanded the level of respect that is beyond the imagination of my American friends here.”

He arrived in the United States on July 4, 1976, the day of the country’s Bicentennial. Tall ships bristled in New York Harbor as Zaki’s plane descended.

He jokes now that he thought the ships had assembled to welcome him. The reality was starkly different.

Two immigration officials interrogated him for ninety minutes. They did not believe he was here to explore business opportunities.

“They said that young people like me, who were from poor Asian countries, had no idea how to explore business opportunities,” says Zaki.

The officials recommended him for deportation and shunted him to another functionary, who pulled everything from Zaki’s two suitcases. He stopped when he came to a box that held a Pan American World Airways frequent flyer card, as well as a membership card for InterContinental Hotels.

“He started apologizing profusely,” says Zaki. “He thought I must be a gentleman businessman. I owe my first entry to the U.S. to those two pieces of plastic,” Zaki says.

The date of his arrival was coincidental, but the symbolism was apt. Zaki was making a declaration of independence. Fresh from visiting Switzerland and England, he was searching for a place to settle in the West.

His grandfather would never have allowed it; he would have insisted that Zaki stay in Pakistan and continue the family’s legacy of service.

But his grandfather was gone, and Zaki, who’d spent two years working as a management trainee in a bank in Karachi, the country’s biggest city, was ready to make his own way. He wanted to start a rug business, and he didn’t want to do it in his homeland.

“The army was taking over again and again. It was a military dictatorship. That’s what bothered me a lot,” he says.

While staying with a cousin in New York, he called his former professor, Wheeless, who, like most educators at Forman Christian College, had taught there for a few years, then returned to the United States.

Wheeless was chairman of the department of history and political science at High Point College, now High Point University. He invited Zaki to stay with him and his wife, Mary.

Zaki accepted. He knew nothing about High Point. He intended only to refresh his friendship with the Wheelesses.

It was summertime, during the holy month of the Ramadan, which requires observant Muslims to pray intensely and fast from dawn to dusk. The Wheelesses usually ate supper promptly at 6 p.m., but during Zaki’s stay, they never ate before the sun went down, when he could join them.

“I’ve never forgotten that,” says Zaki.

Another thing Zaki couldn’t shake: Carl Wheeless’ insistence that he open his rug store in High Point, the home of an international home furnishings market. The city also was a center of furniture manufacturing, and, at the time, had more retail square footage devoted to furniture than anywhere in the world.

Zaki had no money. Pakistan forbade the transfer of funds outside the country. Wheeless had an answer for that, too: an introduction to Fred Alexander, the president of High Point Bank.

Zaki’s friends and family thought he was nuts to consider High Point. He understood why. He was a big-city kid, used to the depth and breadth of culture in cities like Lahore and Karachi. High Point was, by comparison, a tiny village.

At 31, Zaki was a single man and a devout Muslim. His social life in High Point would be severely limited. He knew of only one other Pakistani or Muslim in town, a professor at High Point College. There were no mosques around.

But he had the Wheelesses and their friends.

And he had a financial backer.

He took a chance in 1977.

Zaki secured a loan from Alexander, rented a store on Main Street and moved into an apartment.

He had no furniture. He slept on a bare floor. His softest rugs were for sale, not for sleeping.

He prayed at home. At work, he worshipped behind a closed door.

He ate lunch at Holiday Inn downtown. A bowl of vegetable soup with bread cost a dollar. For supper, he went to the K&W Cafeteria, where he bought three cups of vegetables for 25 cents each. A biscuit was 10 cents.

“My dinner cost 85 cents, plus tax,” he says. “That went on for a long, long time.”

Lithe and spry for his age, Zaki glides around his showroom with ease. An inveterate walker, he says he has ambled through every section of High Point to familiarize himself with the town.

“I have never felt threatened,” he says.

He burns more calories by walking around his cavernous showroom, where the inventory of 12,000 to 15,000 handmade rugs lie in short stacks.

When customers want to see the goods, Zaki and his assistants stoop, grab and flip the edges of rugs like dense pages of gigantic books.

Zaki personally selects each piece during buying trips to Pakistan, India, Iran and Turkey. His rugs range in price from $29 for a 1-by-2 foot wool rug, to half a million dollars for a 16-by-26 foot silk masterpiece.

Approximately 7,000 rugs fly out of the showroom every year. Ninety percent go to American addresses, 10 percent to foreign countries.

Zaki won’t divulge his customers’ names, but he says they include business executives, politicians, entertainers and other celebrities, many of whom have referred their friends.

In forty years, Zaki’s High Point customers never have accounted for more than one percent of annual sales.

But Zaki says he never thought about setting up shop in a bigger city.

Rug merchants, he knew from the beginning, had a poor reputation. An iterant lot, they often skipped town, leaving behind frayed rugs and nerves.

Zaki’s plan was to stay put, be accountable for what he sold, and educate people about Oriental rugs.

“I tell my customers, ‘You know, there is a salesman who is more dangerous than a used car salesman, and that’s rug salesman.’ There is a reason: There is nobody as ignorant of cars as they are about Oriental rugs, and that ignorance is likely to be exploited.”

Zaki survived by attracting out-of-town customers, mostly by word of mouth.

“I was invited to speak to many groups from many towns and states on many subjects: religion, culture, rugs, business ethics, the Soviet Union invasion of Afghanistan, the Iranian crisis after the shah was overthrown, the subdivision of the Indian subcontinent, the standard of living in poor countries compared to the standard of living in the United States,” he says. “Maybe that helped.”

So did his customer service and the quality of what he was selling.

In forty years, the Central North Carolina Better Business Bureau has received no complaints about Zaki Oriental Rugs.

“To be in business forty years and never have a complaint filed with the BBB – yeah, it’s a rarity,” says Kevin Hinterberger, president of the local BBB.

Zaki has been Mr. Main Street U.S.A. in more ways than one.

When he outgrew his first store at 138 South Main Street, he built a bigger one at 1634 North Main Street. When he outgrew that location, he donated the building to the Chamber of Commerce and built his third and current showroom at 600 South Main Street.

He donated yet another Main Street building to High Point Community Against Violence, an agency that works with High Point Police and the state prison system to give job training and support to people who have been convicted of violent crimes.

His faithfulness to High Point has won him many friends. They regularly seek his gentle advice on business and personal matters.

“I have a cousin who pulls my leg. He says, ‘You should charge $200 an hour for consulting, you’d make more money,’” Zaki says, laughing.

His specialty since 9/11: Answering questions about Muslims abroad and locally.

Zaki isn’t as rare as he used to be.

He estimates there are 700 Muslim households in High Point and the surrounding smaller towns. High Point is now home to two mosques. A third is under construction.

Many local Muslims work for textile and apparel businesses. Their bosses flock to Zaki with questions about situations involving cultural differences.

“Just about every time, I find out it’s the result of them having no communication with their Muslim employees,” says Zaki. “There’s no conversation. I’m glad they come to me; it’s part of my mission to help promote understanding between people of different ethnic backgrounds, but for God’s sake, talk to your employees. Ask them.”

By age 55, Zaki was a confirmed bachelor in the eyes of everyone but a rug merchant friend in India. He kept introducing Zaki to candidates.

Nothing took.

Then, in the year 2000, his friend flew him from Calcutta to Mumbai to meet Rashida Wawda. She was 37, older and less flashy than the other women his friend had introduced him to. Also a Muslim, Rashida was a schoolteacher and a yoga teacher.

“She wasn’t a stay-at-home girl waiting for a proposal,” says Zaki.

They lunched with a throng of relatives and friends. After lunch, they talked for three hours, always with chaperones hovering, never sitting closer than arm’s length. By sunset, Zaki proposed.

“I thought she would be a sincere life partner and that she would be good to my family. It turned out that way. I am fortunate,” he says.

The two of them are dedicated to helping others.

Rashida’s focus is the Al-Aqsa Community Clinic, a health clinic that she founded with her friend, Amal Khdour. The clinic provides care for people who cannot afford insurance or medical treatment elsewhere.

Thirty-four doctors and 100 other volunteers staff the clinic, which used to be located in Greensboro but moved to a bigger location in Burlington last year.

“A clinic run by Muslims providing services for all,” reads the Al-Aqsa website.

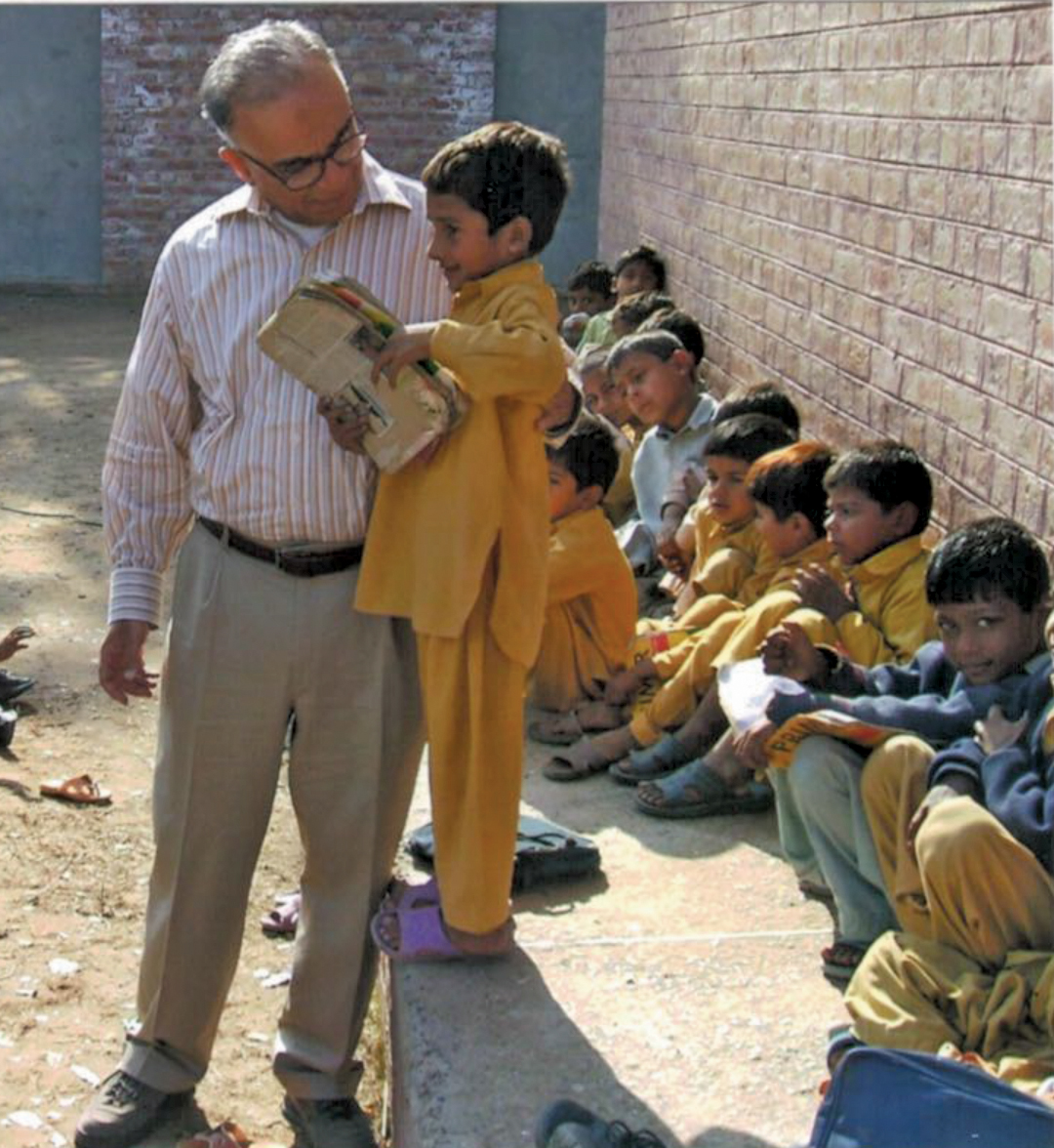

Zaki’s pet cause is a foundation called Friends of Aabroo, which he started in Pakistan several years ago. He registered the organization as a 501(C)(3) in the United States last year.

Aabroo is a Farsi word for dignity and integrity.

The foundation operates free schools for 4,000 boys and girls around Lahore. Many of the students are orphans. All of the teachers are women.

“They are more nurturing, especially with small children,” says Zaki.

Volunteers feed lunch to the students. Often, it’s the only daily meal the children get.

The challenge, Zaki says, is to persuade impoverished parents and guardians to let the children attend school instead of sending them to menial jobs for 15 to 20 cents a day.

He admits that low wages await the older teenagers and young adults who do the tedious work of hand-knotting the rugs he buys from vendors.

“At least they make both ends meet,” he says. “They’re a little better off.”

Those workers’ children would be welcome at the Friends of Aabroo schools, too, he says.

More education in that part of the world would make everyone safer. With no hope for a better life, and little exposure to outside ideas, children can become easy marks for terrorist recruiters, who literally promise them heaven for sacrificing themselves.

“Until we can bring those kids into school to make sure they are properly educated, properly trained, there is no way we can put an end to this terrorism,” Zaki says.

He aims to raise enough money through the foundation to construct school buildings for all Aabroo students and those on the waiting list.

He realizes that many Americans are nervous about strengthening relations with Muslims at a time when some Muslims are intent on harming the United States, but he sees hope in the numbers.

“According to some surveys, .016 percent of Muslims are willing to hurt non-Muslims, and, by the way, they’re killing more Muslims than they are killing non-Muslims,” he says. “If we are going to fight that, we need more than 99 percent of Muslims on our side, rather than staying away from them.”

Reach out. Branch out. Put your money where your mouth is. That’s Zaki’s advice on global and local issues. He wishes more High Pointers would invest in local charities and businesses.

“They don’t invest nearly enough in this town,” he says.

And he would like to see more people, especially affluent people, push themselves outside their normal confines.

“We all have an obligation to get to know something about the world today that we didn’t know yesterday, and the closer the area is to us, the greater the obligation,” he says.

“So, do we get to know something about our town, or do we stay very comfortable in our own very, very small comfort zone? If we have lunch and dinner with the same people, and if we go dancing in the ballroom and in the country club with the same people, we may consider ourselves sophisticated, but the reality is exactly to the other extreme.” OH

Maria Johnson is a contributing editor of O.Henry.