How JoAnn and Bill Owings became guardians of a proud Triad legacy

By Nancy Oakley • Photographs by Amy Freeman

The view from the front porch, revealing a graceful fountain in the side yard, convinced JoAnn and Bill Owings to purchase their historic home on High Point’s Parkway some 30 years ago. “It was the yard,” JoAnn says emphatically. “The gardens were beautiful. You could see, even though everything was overgrown, this yard was beautiful.” Towering oaks, magnolias and other deciduous trees sheltered a massive lot — four lots, actually — choked with wisteria and fallen limbs. “Leaves were everywhere,” JoAnn recalls. “We didn’t even know there were boxwoods,” she adds. The condition of the house was equally daunting. “We walked through, walked out and shook our heads, and said, ‘There’s no way,’” Bill remembers. A litany of problems stemmed largely from plumbing leaks: “Holes in the ceilings — it was just gone in the living room and dining room.” The wall between the music room and dining room was literally falling down.

But on a second visit, the Owings began to reconsider. They both loved history and had always admired the Neoclassical architecture of the house, which they’d passed many times, living nearby in a smaller abode. But at that juncture in their lives, around 1990, with two daughters, a 10-year old and an infant, they were outgrowing their dwelling in the neighborhood so conveniently located near Bill’s base at High Point Medical Center where he works as an anesthesiologist. Ultimately, it was that view from the porch, with the brick walk and the fountain, its aqua-colored walls surrounding a sculpture of a mythical imp wrestling a fish that seized Bill’s imagination. “You can’t find this anywhere, anymore,” he says, referring to the Italianate water feature. “I think she put that in during the late ’40s, after World War II,” JoAnn reflects. “It’s almost as if she went to Italy, went on a trip, came back and said, ‘I can do that.’”

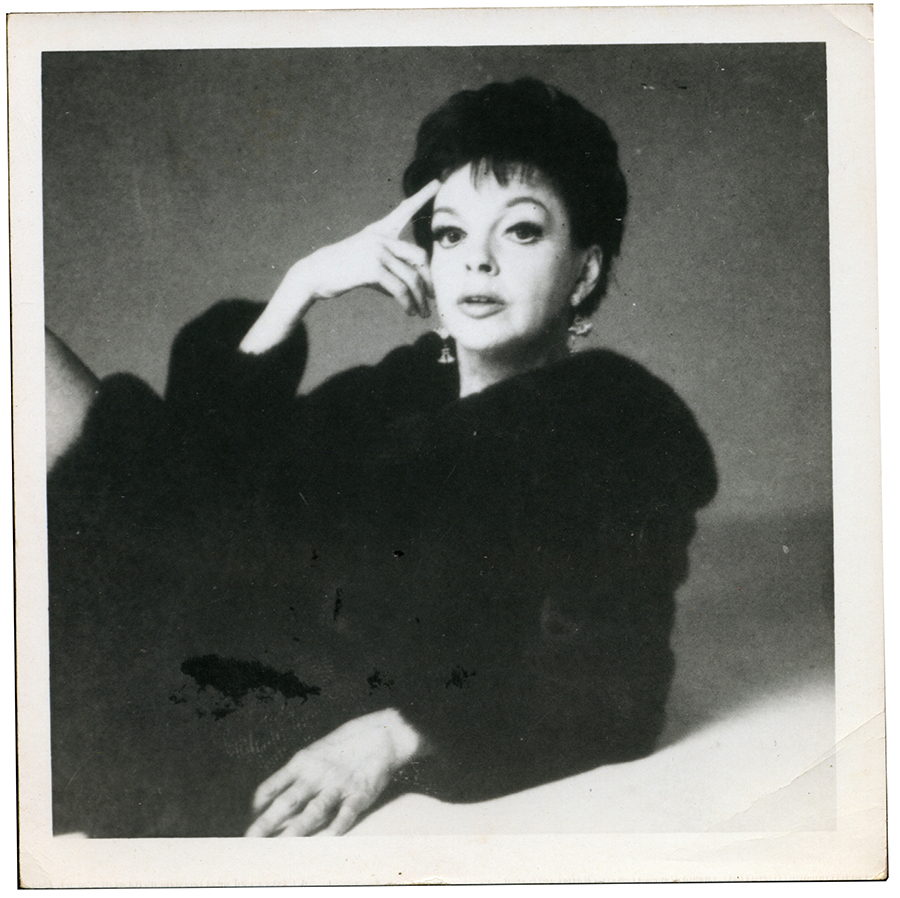

“She” was Lola Lee Blanks Hudson, and it appears there was very little she couldn’t do. An accomplished Tennessee belle, Lola with her sister LaVerne studied at the Memphis Conference Female Institute in Jackson, Tennessee, in 1903 before taking up teaching music in Arkansas. A photograph around this time reveals a bright-eyed young lady, her dark hair piled high in Gibson-Girl fashion contrasting with a slight impish smile. Lola acquitted herself well as “a musician of rare ability and marked talent . . . [possessing] a smooth, even touch and is worthy to be called an artist,” enthuses a reference letter from one of her teachers from American Conservatory of Music – Chicago. “They were wonderful piano players,” says Lola’s grandson William Pennuel (“Penn”) Wood, whose father Elliott Sherrill Wood founded Heritage and Henredon furniture companies, among others. Over the years, Penn Wood, vice president of Woodmark Originals for 19 years, has served High Point on a number of boards, including the N.C. Shakespeare Festival, High Point Arts Council as well as the statewide Museum of History Associates. “Mrs. Hudson read music,” Penn Wood recalls. “LaVerne played by ear.” They even cut a record, which he describes as “a hoot to listen to — a lot of ragtime.” In later years, as Bill Owings heard it, the sisters would invite the neighborhood children to play in the vast yard, with pocket gardens, a fish pond and Lola’s whimsical animal sculptures on Sunday afternoons. “And if they found a four-leaf clover the sisters would play them a duet,” he says.

But that was long after Lola had come to High Point as a young matron, having met and married another Tennessean, Homer Tyre Hudson Sr. He and his older brother, Charles Crump, better known as “C.C.”, would have an enormous influence on the Triad, and particularly Greensboro, with what began as a modest clothing operation, Hudson Overall Company, later renamed Blue Bell, which would morph into blue jeans giant Wrangler and give the city its nickname, “Jeansboro.”

As Penn Wood tells it, the boys’ father, a widely respected professor in eastern Tennessee, had died at an early age. Their mother remarried into the Graham family, which had North Carolina connections in Asheville and Pleasant Garden. When an aunt in Pleasant Garden died, leaving C.C. some money, the young man ventured east to the Gate City, taking a job sewing buttons at an overall plant, Hunter Manufacturing. “This work commanded wages of twenty-five cents per day,” writes Wood in a personal family history. He goes on to explain that the job afforded C.C. the opportunity to learn every facet of the business — from manufacturing and marketing to merchandising, sales and distribution. Thus, the young man was well-positioned, when his employer went out of business: With enough saved earnings to acquire a line of credit, he bought five sewing machines and, as many in Greensboro know, in 1904 set up shop above the former Coe Brothers Grocery on South Elm Street. Homer, living in West Virginia with Lola and their growing family, joined the enterprise.

Buying tightly woven “deeptoned” denim from Cone, the brothers fashioned work clothes so prized among the engineers on the trains pulling into the Gate City, just a stone’s throw from the Coe Grocery loft. They would frequent the fledgling business to buy overalls. On one of these visits — or so local lore has it — one of the train engineers asked about a brass bell on one of the Hudson brothers’ desks, perhaps a memento from their deceased father’s teaching career, with the curious blue patina from the denim lint. And so the legendary brand’s backstory, apocryphal or not, was born.

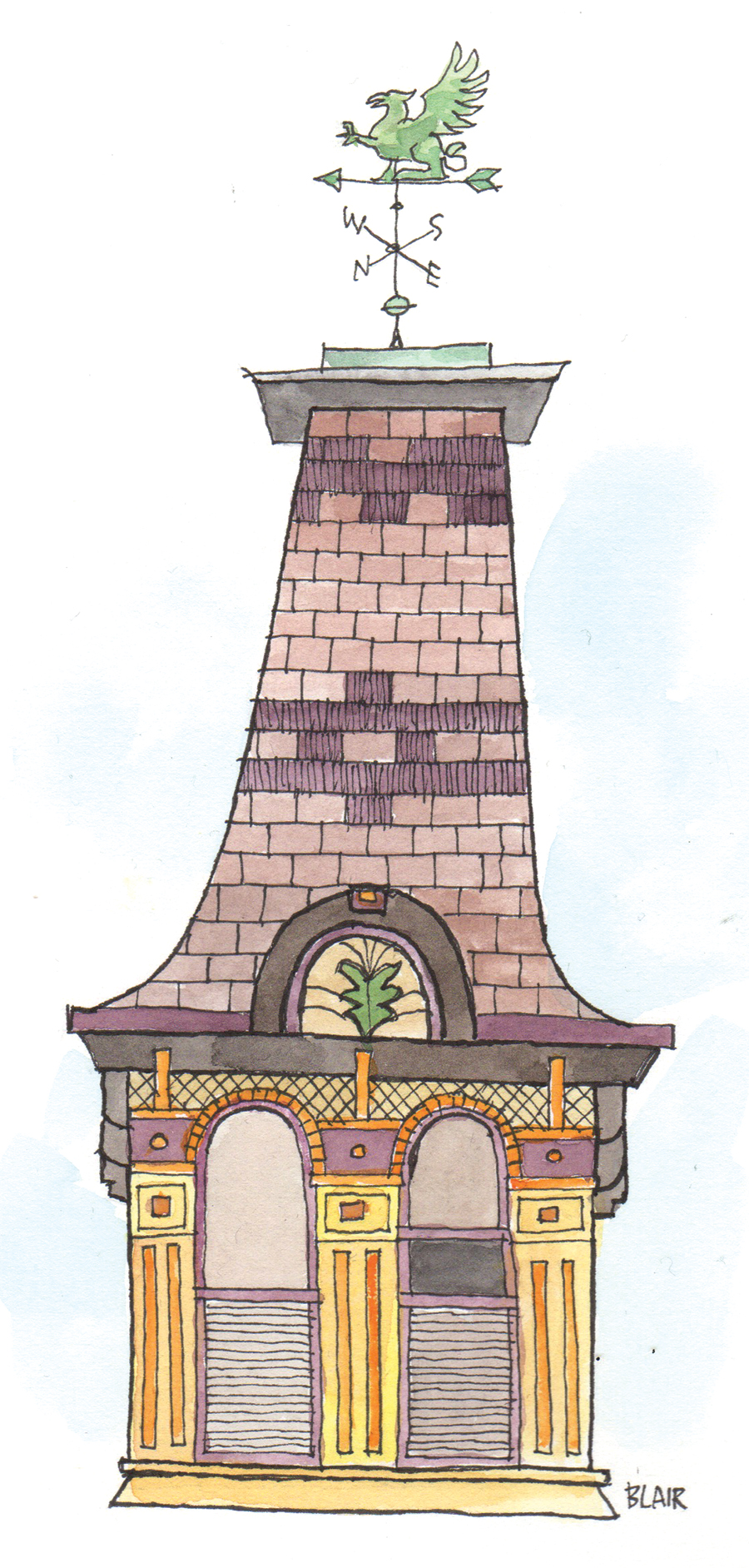

Relocating to different manufacturing sites throughout downtown Greensboro as it expanded, Blue Bell, by 1919, boasted 250 employees and operating expenses totaling more than $600,000. Wood writes. “ . . . what a boon to the local economy . . . the brand suggests a strictly Southern product; the cotton is raised here, the goods manufactured here and the overalls fashioned here.” That same year, Homer Hudson purchased the High Point Overall Company, which would be known for its Anvil Brand work clothes. Three years later, Homer and Lola Hudson built the brick Neoclassical Revival at the far end of Parkway, which they would dub “Home-Lea.”

“Parkway,” says Benjamin Briggs, executive director of Preservation Greensboro and native High Pointer, “was an earlier iteration of Emerywood.” Before the latter subsumed the street, which became the busy thoroughfare it is today, Parkway — and particularly the corner where the Hudsons built — was “kind of like a suburban estate,” Briggs explains. Not so unusual, considering this was the period when the power elite were fleeing grimy industrialized cities and dust-filled factories for literal green pastures.

Briggs has memories of seeing the overgrown gardens when he was child riding the school bus in the 1970s. “They were derelict and overgrown. Wooden features had rotted away. But the bones were still there,” he recalls. The Neoclassical house (now listed on the National Register of Historic Places as a supporting structure for High Point’s Uptown District) is distinctive for that portico that so entranced the Owings. “There are some stylized details on the columns that are delicate; dental molding on the capital; a demi-lune window over portico; brick lentils over capitals,” Briggs offers. According to Penn Wood, the brick, and particularly its crisp white mortar pointing, was a source of pride for Lola Hudson. He indicates it in a photograph of Lola’s daughters, La Verne (Wood’s mother) and Hybernia, two bobbed flappers standing hand-in-hand in front of the arched doorway. The porch later served as the setting for a group photo accompanying a society feature in the High Point Enterprise. The story describes a bridal luncheon that Lola hosted in 1952, the year Homer retired: “Magnolias banked the mantel and were used elsewhere in the living room to which guests were invited on their arrival. Yellow snapdragons were combined with Madonna lilies and lacy gypsophila for the exquisite centerpiece used on the buffet table. . . After being served from the dining room table, guests found their way to the garden room, so named because it overlooks Mrs. Hudson’s lovely sunken garden.”

“She was a student of gardens,” says Wood of his grandmother, a founding member of High Point’s Mid-WeekGarden Club, established in 1923, for which and she and sister LaVerne would provide musical entertainments. He recalls touring destination gardens and sites like Natural Bridge, Virginia, with his grandmother en route to Washington, D.C., to visit relatives. “It was fascinating as a young boy.” He also remembers her visiting his mother in Sedgefield, where he grew up. One summer, he recalls, Lola planted her entire lower garden in soybeans. “Supposedly they put nitrogen in the soil. It looked so rural,” he laughs. “But as a gardener, she would have been interested in the nutrition of the soil.” Lola, after all, came from a long line of planters, starting with the Blankses of Tennessee, who were descended from early settlers along Virginia’s James River. Her parents, Francis Marion “Frank” and Jefferson “Jeffie” Lee Gill Blanks ran the Riverby Inn in Swannanoa in the 1930s. Wood notes that the family tended a large vegetable garden that would feed the inn’s guests.

He adds that Homer loved gardening as well, though most of his time was taken up with the overalls business. “We didn’t see much of him,” Wood recalls. “He was nose-to-grindstone and very nervous.” He remembers his grandfather as being a natty dresser — a must for an executive in the clothing and textile business — who acquired a new car every year, usually a Packard, though Wood does remember a luxury LaSalle.

After the sale of Blue Bell in 1926, C.C. Hudson sat on various boards and offered his service to several community and civic organizations, including the Greensboro Chamber of Commerce. “He grew roses,” says Wood. He recalls his great-uncle’s log cabin retreat, Idlewild, designed by architect Charles C. Hartman. It occupied a large wooded lot in the Gate City’s Kirkwood neighborhood before it was dismantled and moved to Snow Camp in 1994.

C.C. died in 1937, Homer, in 1959. Following his death, Lola invited La Verne, also widowed, to live with her. Penn Wood remembers a couple who served as caretakers, “Sandy the driver and Captola, the cook.” But as often happens, when people age, their houses do, too. Lola remained on Parkway until her death in 1974 (LaVerne had died two years prior). By then the house was already falling into disrepair. Subsequent owners did little to keep the place up. Pipes leaked. Ceilings crumbled. The yard became a veritable jungle, as Briggs witnessed from the school bus during his youth, and as the Owings had noticed.

But once they committed to buying “Home-Lea,” which was living up to its punny moniker, they were determined to restore it to as close to its original incarnation as possible, right down to some of the accents, such as a crystal chandelier. “My kids were like, ‘Oh! Let’s put something modern in here!’” JoAnn laughs. But she and Bill remained steadfast in their mission. “Because of the history of this house — we both love history — we didn’t do anything to change its structure,” JoAnn explains, as she stands in its front hall where curved stair banister and inviting sunny living room with chintz coverings intersect. To the right an unusual arched doorway framed by dental molding leads to a compact music room, dominated by a grand piano boasting photographs of the Owings’ grandchildren, and behind it, built-in shelves filled with china. Beyond that is an elegant dining room abutting one of the few changes, a fully updated kitchen. “But,” JoAnn continues with a grin, “We had a lot of remodeling to do!”

So much remodeling, in fact, that it would be two years before the Owings could move in.

A good bit of the work involved replacing fallen molding and restoring the plaster ceilings damaged by water. “It’s a good thing we did it in the ’90s,” says JoAnn, “because today you can hardly find the [crafts]people anymore. Some pieces had to be copied.”

They modified the fireplace slightly, swapping its simpler brick firebox for rich, dark green marble, but kept the plaster medallions just above it and the dental molding along the mantel. These are flourishes that Benjamin Briggs says are distinctive among High Point homes of that period. “You see things in High Point that you don’t see in other cities,” he notes. Populated with wood craftspeople, it’s how this area became a great treasure of detailing.” And how High Point’s residents developed a keen understanding of different varieties of woods. “There are more wood types,” he continues, offering black walnut and tiger oak as examples. He goes on to explain that High Point’s woodworkers were also skilled at creating illusion, using one kind of wood, such as poplar, to create the look of another.

This trick bears out in the pine paneling of the Owings’ sunroom, which they use as a den. Because of its rosy hue, it appears to be made of cherry. “It was built on in 1948,” says Bill of the addition. They know the precise date because during the remodeling they removed some damaged wallpaper inscribed by the craftsman who hung it. The inscription, JoAnn remembers, “said something about World War II, and he had signed his name that he had done this wallpaper in 1948. He had the neatest handwriting!”

She goes on to say that the room is the Owings’ favorite, and they use it “all the time,” for relaxing, watching TV and growing several plants, like the Meyer lemon tree, which produced enough fruit for lemonade last Thanksgiving.

It’s easy to understand the appeal of the space. Large south-facing picture windows — their original Venetian blinds refurbished — look out onto the wooded portion of the vast lot below. This would have been the “garden room” alluded to in the High Point Enterprise article chronicling Lola Hudson’s luncheon. With seven heaters warming the room from a water-based system, also original (though the Owings did add air conditioning to the house during the remodeling), the room “stays so nice in the winter,” JoAnn notes. Conversely, the ample shade from the veritable forest outside keeps the temperature down in the summer. “There’s incredible shade,” says JoAnn. “If people only knew: Don’t cut your trees down! It’s truly 10 degrees cooler. And the breeze comes through, and you’re protected from the bad winds, because the leaves take the wind.” And as Bill observes, “Even though you’re in the middle of town, in the summertime, when the trees come out, you really can’t see anybody’s houses.”

Another curious feature of the sunroom: cork flooring. “That was Dad’s idea; his office at Heritage had cork floors,” says Penn Wood, explaining that their inspiration came from the Whalehead Club, a 1920s-era duck-hunting lodge in Corolla, on North Carolina’s Outer Banks. “Between the dogs and the kids we’ve had, it doesn’t last,” JoAnn observes, showing some areas where the cork has pitted. “But I’m keeping it. The sound quality [of the room] is incredible.”

One might think kids and dogs would be incompatible with a historic house, but JoAnn maintains just the opposite. “Didn’t they build them then for families? For a lot of people? Big halls, lots of staircases, lots of rooms, not bumping into each other,” she posits, as she climbs the stairs to the second-floor bedrooms, some adorned with the accouterments of their four childrens’ formative years: fishing rods, prints and mementos of Bald Head Island, the family’s longtime vacation spot. A decidedly feminine room — painted a pale shade of lime with floral accents — occupies one corner. Next to it is a nursery for when the Owings’ empty nest fills up with visiting grandchildren, and one level up is an attic converted to an apartment. “Our eldest son got to move to the third floor and that space. He probably had some good parties up there!” Bill jokes.

The master on the second floor, directly above the cork-floored sunroom, is another rare change the Owings made: enclosing what used to be a sleeping porch. The room is simply appointed, save a delicate avian pattern on the drapes, as if the decorative birds have flown in from the surrounding trees outside.

Its windows face west, overlooking the expanse of green lawn that abuts a side street. Glimpses of a plastic pink ribbon marking an electric fence around the periphery of the entire property, all four lots’ worth, suggest the presence of the latest member of the Owings’ family: a boisterous 6-month-old Australian Shepherd named Baxter. From the upper patio just outside the kitchen door, he can be seen bounding across the grass toward the fountain and the brick retaining wall currently being repointed by an Archdale mason. Closer to the house is a pond, one of the Owings’ few additions, with two graceful ibis sculptures. Baxter serpentines around Bill as the two make their way up the gravel driveway below. “He ate my furniture! It was wicker,” JoAnn laughs as she points to a sitting area facing south, overlooking the woodsy portion of the yard, dotted with daffodils in early spring; a tree house, where the Owings’ children and now grandchildren play, is set farther back. Around the corner is a dining table where the family takes meals in warm weather. It overlooks the fountain and pond below. JoAnn points to the moss growing on what was once Lola Hudson’s cement table. “There’s plenty of moss around this house. It’s beautiful, like an enchanted garden,” she muses. She says she and Bill have added little to the yard since they uncovered it all those years ago. “Gosh, we must have 70 or 80 English boxwoods,” he says, expressing concern about a blight that’s currently tearing through Virginia. Understandable, considering the blight could imperial an unusual feature, an arched hedge on the opposite, east side of the house that shields an open side porch.

“It’s exciting to watch the family put the gardens back,” says Benjamin Briggs. “It’s much appreciated. So appreciated, that JoAnn was invited to join Lola Hudson’s old stomping ground, the Mid-Week Garden Club. But then, things have a way of coming full circle. On occasions when Penn Wood or his brother, Chuck, are hosting visiting relatives, “we take them through the house and yard,” says Bill. “They think somewhere in the backyard is a fish pond. I’ve never turned it up. That’s why we built our own little pond in there.” The Owings stopped stocking it with goldfish years ago, because, “the cats in the neighborhood ate those,” JoAnn explains. But no feline would dare enter the premises with Baxter patrolling it, charging around the boxwood hedge, down the brick walk to the fountain and across the lawn, pausing to roll on his back on the cool carpet of grass. Who knows? Maybe one day he’ll turn up a four-leaf clover. And if he does, no doubt the faint strains of a ragtime duet will echo up and down Parkway and through the towering shelter of trees. OH

Nancy Oakley is the senior editor of O.Henry.