Gallery

Extreme Close-Up

For photographer and painter David Wasserboehr, God is in the details

By Nancy Oakley

A patch of blue becomes a patchwork of aqua, white, violet and a subtle trace of pink. And red isn’t merely red, so much as a series of streaks in white and crimson and orange. You don’t realize that you’re looking at the lip of a glass vase and the base of a flower petal set inside it — until you cast a glance at David Wasserboehr’s companion photographs of entire blooms and stems. But these, too, reveal the meticulous wonders of Nature’s construction — the fuzz on the anthers of stamen, the tiny yellow ruffles dancing around the edges of a variegated red tulip, the fine ribs of a lily’s white petal.

A patch of blue becomes a patchwork of aqua, white, violet and a subtle trace of pink. And red isn’t merely red, so much as a series of streaks in white and crimson and orange. You don’t realize that you’re looking at the lip of a glass vase and the base of a flower petal set inside it — until you cast a glance at David Wasserboehr’s companion photographs of entire blooms and stems. But these, too, reveal the meticulous wonders of Nature’s construction — the fuzz on the anthers of stamen, the tiny yellow ruffles dancing around the edges of a variegated red tulip, the fine ribs of a lily’s white petal.

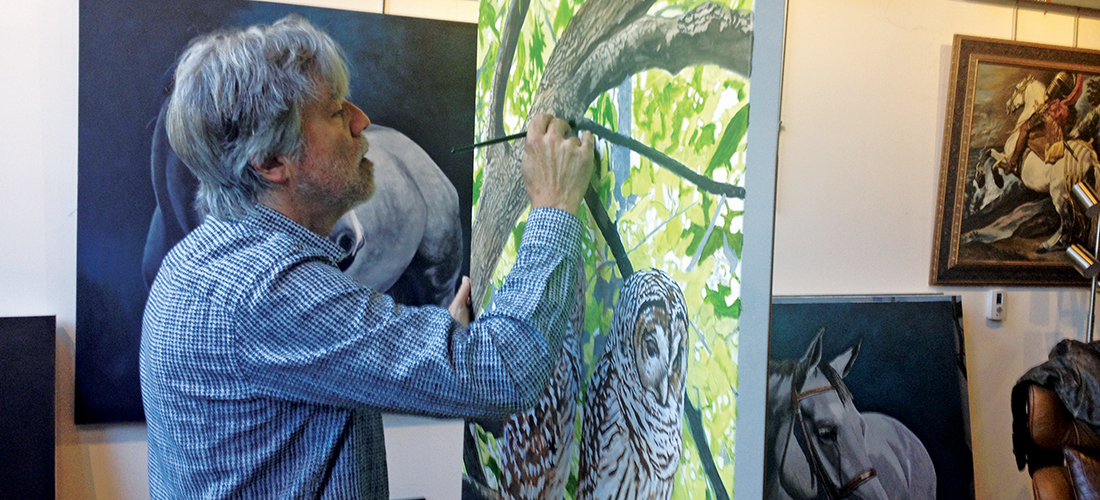

“I’ve always loved detail,” says Wasserboehr, a classically trained painter who seized on digital illustration when the genre was in its infancy. Having learned from “really cool, old painters” when he was earning his B.F.A. at University of Massachusetts Dartmouth (Southeastern Massachusetts University in his day), Wasserboehr worked in traditional media, such as oils and watercolors, parlaying his skills to ad agency gigs. “I did everything by hand,” the artist recalls of the early days in his career.

But the tools of his trade were changing, as the advertising world embraced digital technology. And Wasserboehr would also make the great digital leap forward, particularly in the mid-1980s, when he moved to Greensboro.

He had been living in New Jersey when his sister, Pat, a UNCG art professor, called and invited him for a visit, adding, “I have someone I’d like you to meet.” That someone was to become the artist’s future wife, Bonnie Burkett. She had no interest in living in New Jersey, so Wasserboehr relocated to the Gate City, picking up a freelance assignment at the News & Record.

He had been living in New Jersey when his sister, Pat, a UNCG art professor, called and invited him for a visit, adding, “I have someone I’d like you to meet.” That someone was to become the artist’s future wife, Bonnie Burkett. She had no interest in living in New Jersey, so Wasserboehr relocated to the Gate City, picking up a freelance assignment at the News & Record.

The newspaper, he explains, “was one of the first to get a bank of Mac computers. I began setting type on the computer.” He was an immediate convert to Apple Macintosh systems and invested a whopping sum of $17,000 for one of its initial rigs (computer, color monitor, scanner and black-and-white laser printer); by the early ’90s he had learned digital illustration on Adobe’s first graphics programs. As one of only a few folks in town at the time who had such skills and the proper equipment, Wasserboehr carved out a lucrative freelancing career making digital illustrations for various clients, Pace Communications among them. “Now everybody does it,” he says. But the experience led to an epiphany: “I saw the future and it was filled with digital tools combined with classical training.”

These days Wasserboehr “bounces back and forth” between the old and the new, painting miniatures as small as 2 inches or 54 millimeters, and creating digital paintings (using a software program called ArtRage). The artist also combines his craft with his love of history. He was once asked to restore an “old, damaged and faded photograph.” After scanning it and “drawing out the old information in the pixels still hiding in the scan,” Wasserboehr brought to life a portrait of his client’s grandmother; it revealed a cameo brooch — the very one his client kept in her jewelry case, never knowing until that moment it had belonged to her grandmother.

These days Wasserboehr “bounces back and forth” between the old and the new, painting miniatures as small as 2 inches or 54 millimeters, and creating digital paintings (using a software program called ArtRage). The artist also combines his craft with his love of history. He was once asked to restore an “old, damaged and faded photograph.” After scanning it and “drawing out the old information in the pixels still hiding in the scan,” Wasserboehr brought to life a portrait of his client’s grandmother; it revealed a cameo brooch — the very one his client kept in her jewelry case, never knowing until that moment it had belonged to her grandmother.

Helping clients, Wasserboehr says, adds meaning to his life. So much so that he lends a hand to the Greensboro History Museum restoring documents (“a lot of Dolley Madison stuff,” the artist clarifies). Working from scans of old, worn documents, some from the 1700s, Wasserboher creates facsimiles that can be exhibited, giving the originals a break from unrelenting light and humidity, and general wear and tear. “I’m restricted,” he says, explaining that his work “must include tears and dirt on the documents.” So realistic are his reproductions that one of the archivists had to check to see which documents were the originals; Wasserboehr’s boss had other ideas, jokingly suggesting, “If you need another line of work, you could probably be a counterfeiter!”

But his wife, Bonnie’s “insane” passion for gardening led him to macro photography. “We go to Walmart to look for housewares and the next thing you know, we’ve got $50 to $60 worth of plants,” Wasserboehr says. “I go out in the yard and dig holes.” A few years ago they fashioned two beds in their backyard, “where we could plant roses, lilies, mums, cornflowers and other beauties,” Wasserboehr recalls. As the plants grew, he noticed some daylilies occluded by some shade. Their pale color caught his eye and prompted him to reach for his camera.

But his wife, Bonnie’s “insane” passion for gardening led him to macro photography. “We go to Walmart to look for housewares and the next thing you know, we’ve got $50 to $60 worth of plants,” Wasserboehr says. “I go out in the yard and dig holes.” A few years ago they fashioned two beds in their backyard, “where we could plant roses, lilies, mums, cornflowers and other beauties,” Wasserboehr recalls. As the plants grew, he noticed some daylilies occluded by some shade. Their pale color caught his eye and prompted him to reach for his camera.

“I had always loved photography,” says Wasserboehr, who had owned a film camera, and as a tech enthusiast was turning his attention to the high quality of digital photographs. He had been captivated by an online tutorial by Long Island-based photographer Melanie Kern-Favilla, whose work features striking macro photos of flowers set against a black background (a box with a black interior). “So I built a rectangular box and raided my wife’s garden for daylilies,” Wasserboehr explains. He positioned the box on the table in his dining room, which doubles as a studio, and which catches the morning light on one side. Placing the flowers inside the black box, Wasserbohr learned to manipulate where the light falls by placing shades — trays, a piece of cardboard, gauze — on top of the box or on its sides. Using his two favorite macro lenses (A Tamron 18-270mm 1:3.5-6.3 lens and a Canon macro EF 100mm 1:2.8 USM lens), he adjusted the setting on his Canon T6i to “manual” and began snapping away. “On the second or third try, it just popped!” the artist recalls. “You know when you go ‘Whoa! This is cool!’ I knew I was on the right track.”

He continued nabbing “perfect specimens” from his wife’s garden (“she’s been a really good sport about it, he adds), favoring taller, vertical flowers — such as the daylilies and tulips, that are sculptural in appearance. “They’re more in-your-face,” Wasserboehr concedes. His painterly eye prompted him to experiment with composition, zooming in on just the lip of that vase, or the base of a petal, for example, to create a surreal effect reminiscent of Georgia O’Keeffe’s paintings. Wasserboehr says he might shoot from unusual angles — lying on the floor, standing on top of a stool — to achieve just the right composition.

He continued nabbing “perfect specimens” from his wife’s garden (“she’s been a really good sport about it, he adds), favoring taller, vertical flowers — such as the daylilies and tulips, that are sculptural in appearance. “They’re more in-your-face,” Wasserboehr concedes. His painterly eye prompted him to experiment with composition, zooming in on just the lip of that vase, or the base of a petal, for example, to create a surreal effect reminiscent of Georgia O’Keeffe’s paintings. Wasserboehr says he might shoot from unusual angles — lying on the floor, standing on top of a stool — to achieve just the right composition.

But his photographs aren’t merely exercises in technique. Wasserboehr tries to avoid any kind of color correction, using Photoshop and Lightroom as little as possible. Otherwise, he says, the flowers “lose their innocence.” His primary aim? “I want to tell a story with these plants.” Such as the peace lily that a friend had given him and his wife some 25 years ago. One day, Wasserboehr happened to notice three leaves on it, each at a different stage: one with a newly unfurled white blossom, another fading to greenish-gray, and a third, shriveled and brown. He plucked all three, placed them into his rectangular black box and started shooting. The result is a poignant statement of the fleeting nature of life. “I am fascinated by the beauty of the full life cycle of the flowers, including their final, wilting moments,” Wasserboehr says. “As I get older I’ve discovered the aging process is very similar to a human being’s . . . all elegant and beautiful!” OH

Nancy Oakley is the senior editor of O.Henry.

For more examples of David Wasserboehr’s work, please visit fwgraphics.myportfolio.com/work.

As his 2011 essay

As his 2011 essay

“

“

Out back, beyond the shimmer of her saltwater pool, is a gated garden where late-summer zinnias, hibiscus and canna lilies linger on with a few valedictory blooms. Beyond this is is a wide natural meadow teems with wildflowers, asters, black-eyed Susan, broom sedge and Joe Pie weed humming with hundreds of bees and butterflies gathering up the final sips of summer’s sweetness.

Out back, beyond the shimmer of her saltwater pool, is a gated garden where late-summer zinnias, hibiscus and canna lilies linger on with a few valedictory blooms. Beyond this is is a wide natural meadow teems with wildflowers, asters, black-eyed Susan, broom sedge and Joe Pie weed humming with hundreds of bees and butterflies gathering up the final sips of summer’s sweetness.

Maria Fangman

Maria Fangman Charlie Heddington & Debbi Seabrooke

Charlie Heddington & Debbi Seabrooke

Diane & Tracy Peck

Diane & Tracy Peck Chris & Robyn Musselwhite

Chris & Robyn Musselwhite Susan Foust

Susan Foust Victoria Clegg

Victoria Clegg David Barnard

David Barnard