Redo, Redux & Release

Thomas Buckley on artful designing — and turning — on a dime

By Cynthia Adams

Photographs by Amy Freeman

Last May, Thomas Buckley and his partner, Cecil Lockhart, left an 800-square-foot, renovated home on Roseland Street for a move of less than one mile. They had bought a Fountain Manor condo in the neighborhood and did what they enjoy most: They started all over with a clean slate.

There was little to pack. The couple’s modus operandi is to take their artwork and a few personal effects with them, and dispense with the rest.

By September, their fifth and latest renovation was completed in just four months, with a few tweaks left in the kitchen. But by the time their newly befriended neighbors blink, the home makeover addicts will be gone again to embark on their sixth redo. (They already have an eye on a new fixer-upper.) Between them, they have lived in California, Connecticut, Colorado, South Carolina and now North Carolina.

A fresh design canvas is just the ticket for the designing duo.

But back to last spring, and the previously sight-unseen condo they now call home. Before the partners bought the Fountain Manor condo, they already knew it was the right price and the right location. “We like a bargain,” Buckley confesses, which is putting it mildly.

But — once seen, the 1,700-square foot Fountain Manor abode (double the size of their former home!) featured dated wallpaper and flooring, and a blasé look. It was stuck in a 1980s time warp. The condo was, by any measure, clean and livable but read much too traditional for their tastes and eclectic artwork.

Buckley set out to do what he relishes, designing on a dime. He established an exceedingly small budget to make their new home hum. The couple’s renovation budget? They look at each other and smile. “$10,000, all in all, including new kitchen appliances.”

Paint — the cheapest of tools in a designer’s arsenal — is also the most powerful.

Buckley enthuses, too, at the Triad’s trove of riches when it comes to furniture and home furnishings! Greensboro offered unparalleled consignment choices, thanks to the area’s being at the epicenter of the furniture industry. Buckley says he can scarcely believe his good luck.

“The thrill of the hunt,” Buckley smiles, to furnish a new space, is his second greatest kick once he has plotted how to make a design fresh and refreshing. For this purpose, he goes right to the “incredible array” of consignment shops that populate the Triad. He points to a coffee table — like all the other furnishings, it appears to be brand-new. (Nothing in the condo appears remotely shabby, but polished and chic.)

“This coffee table is a $2,200 Baker table, and I paid $240,” the designer says with no small amount of pride. “I know high-end furnishings, and I love consignment. I’m totally into repurposing.”

He is quite possibly as addicted to the next new thing, as some are addicted to collecting.

As he explains it, Buckley truly likes cha-cha-changes.

“I’m ready to do it again,” he grins. When working for a client, he occasionally sells something straight out of his home. “I’m very into creating good energies in a space,” he explains. “But I’m not into the pressure to keep up with the Joneses.”

Buckley qualifies this. He likes small change with maximum effect. Meaning, when this designer takes on a new home interior, he enjoys the challenge of a very slim budget.

“Anyone can design with a huge one,” he frowns. But not everyone can reuse, repurpose, reinvent and rejuvenate, all the while honoring the discipline of keeping things to, as he adds, “a very reasonable cost.”

The availability of beautiful things at a bargain still stuns Buckley. Taking advantage of that bounty is simply what Buckley loves, and he is slowly bringing Lockhart around to his point of view. Together, the couple moved from “a big house in Denver, Colorado, to Florida, then to a (N.C.) house, then a townhouse, then to the house on Roseland, and now here.”

Buckley says he’s been designing since he was 10 years old. “After the first design job, I got the Carly Simon album, You’re So Vain,” he chuckles. It was thrilling, to source collectibles, especially art and high-end furnishings, and reinvent a space. And to make money doing it, he says.

Buckley still owns a painting he chose for his uncle when he was only 15 and later inherited. He keeps deeply sentimental things, especially the art that he loves, but all else is up for sale. Or else, he says, it is up for donation.

“You shouldn’t get attached to anything,” Buckley says. Then, Lockhart quietly confesses, “But I do get attached to things.”

Buckley amends, “I did get attached to a Drexel Heritage sofa I once had.” He says this apologetically, as if he needs to explain.

How did this gypsy-spirited design philosophy develop? A growing awareness of mortality made Buckley realize how fleeting life and possessions are.

“I have had health issues. My former partner, Dan, had leukemia, and I took care of him.” The entire experience was deeply affecting for Buckley. It caused him to also redesign his own life, creating one that would not place possessions over meaning. He did not wish to be owned by his possessions.

Furniture, furnishings and other material objects were no longer imbued with the meaning they once had. They simply could serve as a substitute for what he had lost. Buckley landed on the idea that he could approach each home like a Zen garden — one designed without attachment. Lovely and temporary. He could indulge a passion for designing new spaces and the all-thrilling hunt for treasures, without accumulating material objects that tied him down more.

The answer was to design, decorate, and then polish a rough stone until it shone like a diamond, and move on.

“Who needs so much stuff?” he asks plaintively. As his parents aged and their health declined, Buckley frequently returned to their Connecticut home — large and stocked with treasures. He preferred to live simply, with far fewer things.

So, the couple has begun refining the art of moving in only a day when the whim hits them.

Lockhart had to be converted to learn to redo a place, furnish it, then leave it and start afresh. “It became liberating. I resisted it at first, though. But I see the beauty of it now,” he admits.

He still works at various jobs through the week, which include real estate, retail and one day weekly as a hairdresser, his former profession. He likes the variety and freedom.

“When I lived in Greenville, S.C., people bought my house fully furnished,” Buckley says. “I sold it all, because I felt it wasn’t fair to Cecil not to start afresh in our new relationship.”

After the couple bought the Fountain Manor condo, they proceeded to change some of its more dated aspects in record time. They opened up space, removing, for instance, a half wall divider with pickets that impeded the flow of the room. They then claimed a closet, “Which we repurposed into a ‘dry’ wet bar,” Buckley jokes. It immediately upgraded the hipness of the living room. Their next inspiration cost a mere $300 and sweat equity.

“I found a fireplace insert on craigslist,” says Buckley. “I told them I wanted the electric fireplace only.” A new fireplace adds panache and visual interest upon entering the house — where there had previously been none.

Next they undertook cosmetics, ending with the kitchen. Down came kitchen wallpaper that Buckley instantly recognized as a Waverly favorite he had used years ago on design jobs.

Using a color-saturated palette as a better backdrop for their art collection, replacing flooring, and a kitchen upgrade made significant impact for an insignificant investment.

“We had a $10,000 budget and we did it all — kitchen included,” Buckley says with obvious pride. “And that is, the kitchen and all appliances: $4,200 for the appliances. There was an appliance sale and I knew when to buy them.” They kept the cabinets, which were in good condition, except for one section, which was removed to expand the room. The cabinets were painted and given spiffy new hardware. Then, the couple replaced the countertop with a reasonably priced laminate and refinished the floors.

The kitchen is now more open, and a clean, fresh room rather than detraction.

Buckley does have a case of reverse snobbery.

One of the couple’s wing chairs was featured in the February issue of Architectural Digest. Buckley proudly says it is the very chair he sits upon, a $3,000 chair, one he snagged for $300 on consignment. (The thrill of such a deal excites him as much as the beauty of the piece. “I love the Red Collection, and also buy things at the Carriage House nearby.”)

But when it comes to bargain-hunting, it’s the art collection that shows their true colors. Buckley says he scored two framed sketches of the RMS Titanic and the Mauretania.

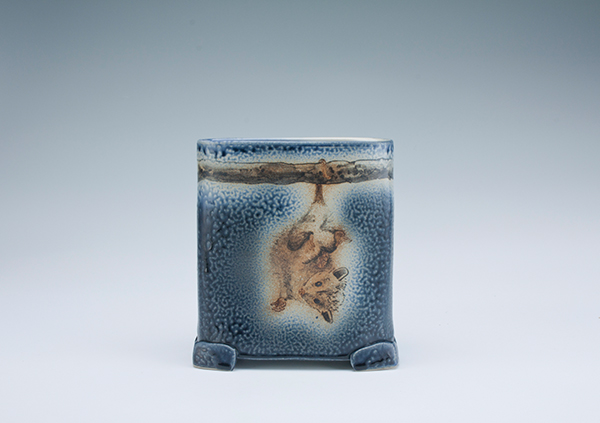

They also own a piece by James Austin, one of many designers to help originate the AIDS Memorial Quilt. In addition to many others, the couple is proud of two works by Jim Hahn, an artist of note who began painting later in life.

Did Buckley buy these pieces of art retail? “Oh, no,” he says, taken aback. That, it happens, is against Thomas Buckley’s religion. Think of him, if you will, as the Warren Buffet of design. In this case, he’s actually the Design Oracle of the wealthy enclave of Greenwich, Connecticut, where most of his family still resides.

But a true home, as Buckley will point out, is not an address. It is where you find meaning. A friend just called them about a house she hopes they will take on, and they are already twitching to do it. It’s smaller than the condo. Not a problem, says Buckley.

“We eventually hope to downsize our way to live in a tiny home,” With this, Buckley shoots a quick glance at Lockhart, who, unfazed, scarcely raises an eyebrow. “Well,” Lockhart points out, “at least this way our closets are always neat and our house is always clean.” OH

Cynthia Adams is a contributing editor to O.Henry and writes for its sister publication, Seasons. She is convinced that style has little to do with money, and everything to do with imagination.

Brother, Can You Spare a Dime?

Thrifty Design Ideas from Thomas Buckley

1. Buckley loves color and advises, “Don’t be afraid of color. Color is one of the cheapest, most dramatic ways to change a space. Also, no color is out of style! So, choose a color you love, and run with it.”

2. Whatever you do, consider keeping your interior classic. “Timeless design is balanced. And, it is a comfort to your heart,” Buckley says.

3. Stay well away from trends. Buckley believes trends may quickly date and limit an interior.

4. Making your house a true home “needs you in it,” says Buckley. Express yourself in your home and it will read as cozy and more distinctive.

5. Consider carefully what your interior actually needs versus what you want, making a distinction in order to control clutter.

6. When buying pieces, buy whatever goes best with what you already have. He advises that you know a piece of furniture or decorative object will work before you commit. “Don’t buy an item just because you like it,” he cautions.

7. Make whatever you have the best you can make it. “I’ve designed a mobile home in Myrtle Beach, and it was great,” says Buckley.

8. Buckley believes that “all art goes together,” saying he doesn’t limit his collection to a single artist or style. In his view, art has the advantage of having no floor space and yet it is transformative.